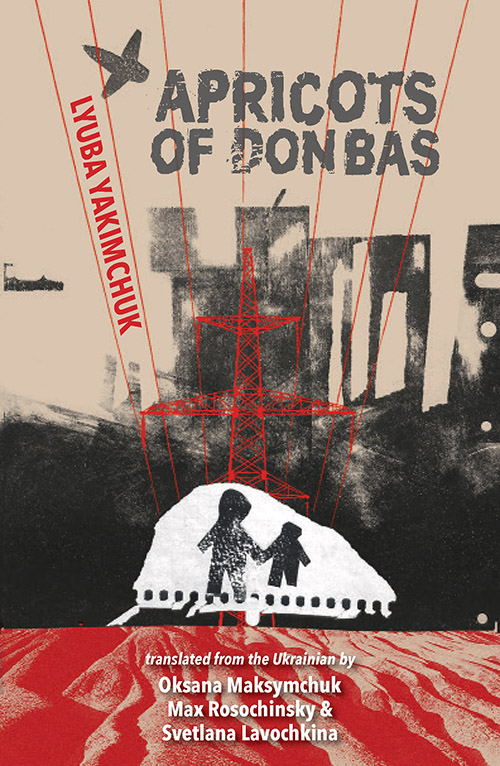

By Ally Britton-Heitz

Lyuba Yakimchuk’s poems are threaded with commentary about and insight into the role of gender in the war-torn Donbas region. Within the namesake for her collection of poems, “Apricots of Donbas”, the stories of Yakimchuk’s family are recounted, revealing the roles that her family and many more have been forced to fill. In the opening canto of this long poem, Yakimchuk not only threads in Slavic gender roles, she also knits a whole picture of her father, a father, who as a man, does not cry, a father that drank, a father that smoked, and a father, that like many others, was battered and bruised by the coal mines (37). These fathers and these men were expected to descend into the mines and many would later ascend into the heavens as a result. Yakimchuk describes the duty of the men and their subsequent fates,

they were twenty

turned twenty

they were looked up to

when they continued the row

by the laws of equation

six deep at the graveyard

and while Yakimchuk’s father did not join these men, his was an unlikely fate (45-47).

Fate for women does not appear to be much more fulfilling, even if it is less deadly. Not only does the role of a woman demand housework, it demands the handling of the coal, it demands daily reminders of the fate that awaits their husbands, fathers and sons. Yakimchuk recounts her experience in a way that highlights the grueling work of an industrial woman,

and I wash the coal

like I’d wash my braids

I crush the coal

like I’d cut potatoes

and as she continues, it is further revealed that the work is hard, that life in Donbas is difficult, but that it is her home,

catch a glimpse of the apricot blossom

supple white apricot blossom

and in the fall

see their yellow curls

from the height of the mine trolley’s flight

(41-43).

It is at this point that Yakimchuk further discusses her family and knits in the role of the Slavic Grandmother, a likely factor of the hominess she feels within the Donbas.

Throughout Slavic folklore, the role of the grandmother is that of a storyteller and Yamichuk’s folklore for the industrialized shows no difference. Yakimchuk’s grandmother shares stories, fables that pose a warning. Her warning in the fourth canto is of the danger posed by the coal mines to the young men. Yakimchuk’s grandmother as she appears in poetry is poignant. It clearly highlights her role as both a storyteller and a protector, delivering an exclamatory “wait!” before depicting the harm that lies within the mines (49). The further description that follows creates a gruesome metaphor that provides insight into the nature of the mines.

don’t come inside

you might not return

like a child of a mother

who doesn’t want to give birth

While gruesome in nature, the poem returns to its folkloric nature in the final lines. It illustrated real-life horrors while invoking a folkloric perspective by assigning such harm and death to the nature of apricots (49). By concluding,

and now when you eat apricots

you find coals inside

Yakimchuk establishes the idea that the death of men in the Donbas is intertwined with the natural world, creating folklore from real, gruesome, experience (51). While the grandmother’s fairytale was didactic in nature, it takes up the same role as other folklore pieces.

Folkloric tales, despite their significance in Slavic and other cultures are often regarded as false, as backward in nature. When hearing of Slavic creatures such as the domovoy and his protection and attachment to a home, a Westerner would likely dismiss the validity of the piece as a whole. As such, those who tell them are often seen as unintelligent, as elderly village women, who may have nothing better to do. While the Slavic reality is that these women are educators, when being translated to English, this meaning is often lost. The same can be said for Yakimchuk’s piece, whether done intentionally or not. Upon their translation to English and arrival into the United States, Yakimchuk’s poems may be seen as an exaggeration, as an ill-fitting description of industrialization, despite the truth behind them. And yet, Yakimchuk makes the connection anyway, because both folklore and the harsh reality of industrialization are what characterize life in the Donbas.

Ally Britton-Heitz is a second-year student majoring in Diplomacy and Global Affairs and Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies. She is an undergraduate fellow at the Havighurst Center for Russian and Post-Soviet Studies