By Harrison Crone

Like many young people who have suffered through the pandemic, I went abroad at the first chance I got. However, the destination of my travel was not usual for an American. No, I did not voyage to France, England, Italy, or Spain; I looked east, towards the mysterious Baltics.

As an American, I found the gap of knowledge I had about this region quite unusual. We learn about France, Germany, and even Poland, but not of the Baltics. Instead of being taught their bravery in the face of Soviet aggression, the only thing we ever hear about the Baltics in America is how sure their defeat by Russia would be. So, to learn more about the region, I embarked on an odyssey that took me through Lithuania.

My adventure began where many other international adventures begin: the airport. I did not know what to expect for my flight abroad; no one in my family had ever traveled internationally, so I was the ‘guinea pig.’ The flights were fine and relatively straightforward, but my lack of knowledge showed through when I landed at Vilnius International. There was a sign before the exit: “CUSTOMS.”

To be blunt, I did not understand and still do not understand how the customs system works. As one could imagine, this was a big issue, especially when you are already in a foreign country. I immediately contacted a professor who was from Lithunaina asking the simple question, “what do I declare at customs”.

Of course, for any who has traveled aboard, this is a silly question to ask; you only declare anything of high value: diamonds, paintings, or rare artifacts. The rarest ‘item of value’ I packed was an $800 laptop that doesn’t turn on unless it is plugged in. The rest of my belongings were deodorant, pink shorts, t-shirts, and other nondescript items.

I can only imagine what was going through her head. She likely thought I brought some ludicrous, expensive items with me to Lithuania. She texted back, “I don’t know, what did you bring”.

Her text, which was supposed to bring about a soothing wave of comfort, instead made me panic more. For about an hour, I sat googling Lithuania’s customs system until eventually giving up and leaving the airport. If I committed some sort of crime, I am deeply sorry, Lithuania.

The drive from the airport to my hotel was as educational as my Google search was before the drive. My surroundings flew by as I quickly learned that Lithuanian drivers love to go way too fast. However, what I did see surprised me; American food: McDonald’s, Italian restaurants, and even KFC. Furthermore, the people there were more fashionable than I ever thought. People wore cool leather jackets with ripped jeans. Meanwhile, I looked lame in a t-shirt and normal denim. For a country that we ignore, its culture is more similar than I expected.

The hotel I stayed at was unremarkable. The bed was passable, as was the staff. The only huge difference between a Lithuanian hotel and an American one is the food offered in the morning. The Lithuanian breakfast was much better than your usual American hotel breakfast. Gone were the terrible ‘southwest scrambled eggs,’ overcooked until rubbery and full of plastic-y veggies. In their place, there were fresh pastries, fruit, and various ‘salads’ (essentially toppings mixed with mayo).

I noticed that overall, Lithuanians are much more creative when it comes time to dine. The last time I had eaten beets before Lithuania was when I was eight. At the time, I was forced to consume the ever-oppressive ‘beet salad’ by my parents. This salad was not like the classic Lithuanian version; it had no mayo, just beets–I hated it. However, the Lithuanians’ use of the beet has made me appreciate the vegetable more (although I am still on the fence about pink borscht–a chilled stew made with buttermilk, dill, and beets).

Another food I found to be interesting was the ‘Cepelinai’ or ‘Zeppelin’. This dish was a potato dumpling stuffed with meat and covered in sour cream and bacon sauce. From an American perspective, it does not sound or looks appetizing. In fact, I found that many of the locals do not like the dish (which is the national dish of Lithuania). However, I enjoyed it and thought it demonstrated the main idea of Lithuanian food: it may look and sound unappetizing, but it is a lot more delicious and unique than American food.

After a hearty breakfast, I finally explored the city and met the locals. Vilnius offers a vast array of architecture, as I learned. The old quarter was known for the red clay shingles on its roofs. Then, quite suddenly, the architecture changed into soviet style architecture, made up of gloomy cement and blocky structures. If you were not paying attention to the architecture, like I was at the time, you would think you were in a different city. As a result, there were many times I got lost in the city, disorientated by the bizarre mixture of buildings.

The sharp architectural differences I noticed in Vilnius were symbolic of the population. The older generation, those born before the fall of the Soviet Union, carried themselves like the Soviet buildings: gloomy, oppressed, and grim. The tour guide I had was born in the 1930s’, and as a result, was a tough, no-nonsense woman. She would create an itinerary and stick to it by the minute, even if that meant forcing the tour group to do activities no one wanted.

An example of this mentality was the day we toured churches. The entire day was spent touring only three churches, with the group spending over an hour standing in one place at an Eastern Orthodox church. When the group wanted to leave, it was denied by the older parishioners, as they had hours more of teaching they wanted to do–we were there for hours.

Like the red clay shingles of the old quarters, the young adults of Lithuania live their life carefree without the fear of others judging them for who they are. My anecdotal evidence of this mentality also comes from the ‘church day.’ We visited a massive graveyard when we stumbled upon a bunch of flowers on a grave. The younger people of the group dared me to smell the flowers, claiming that it was a custom to smell them. As such, I torpedoed down and smothered the flowers with my face. Unfortunately, it was a prank, and the old tour guide yelled at me.

Besides the architecture and the people, the food of Lithuania was also diverse. Lithuanian restaurants resided in every street possible, that is, when not challenged by fast food. For every mom-and-pop Lithuanian restaurant, there was a different cuisine waiting to poach customers. The strategies of these non-Lithuanian cuisines worked on me, and I found myself eating more lasagna than borscht.

My journey to the Baltics taught me much about humanity, food, and how others act when you desecrate a grave. Although I still do not understand customs, I found that this trip was better than my parents or I could have imagined. The people of the Baltics do not patronize you with the smug hospitality you can see at any hotel or resort in America. They do not change themselves to appease foreign tourists or fix things we think are silly here in the States. Instead, they simply give you their culture on a plate (usually borscht) and leave it up to you whether you like it. If you are willing to do the work and stop to smell the roses, or in my case, the flowers of the dead, then the Baltics is a wonderful experience that I cannot recommend more.

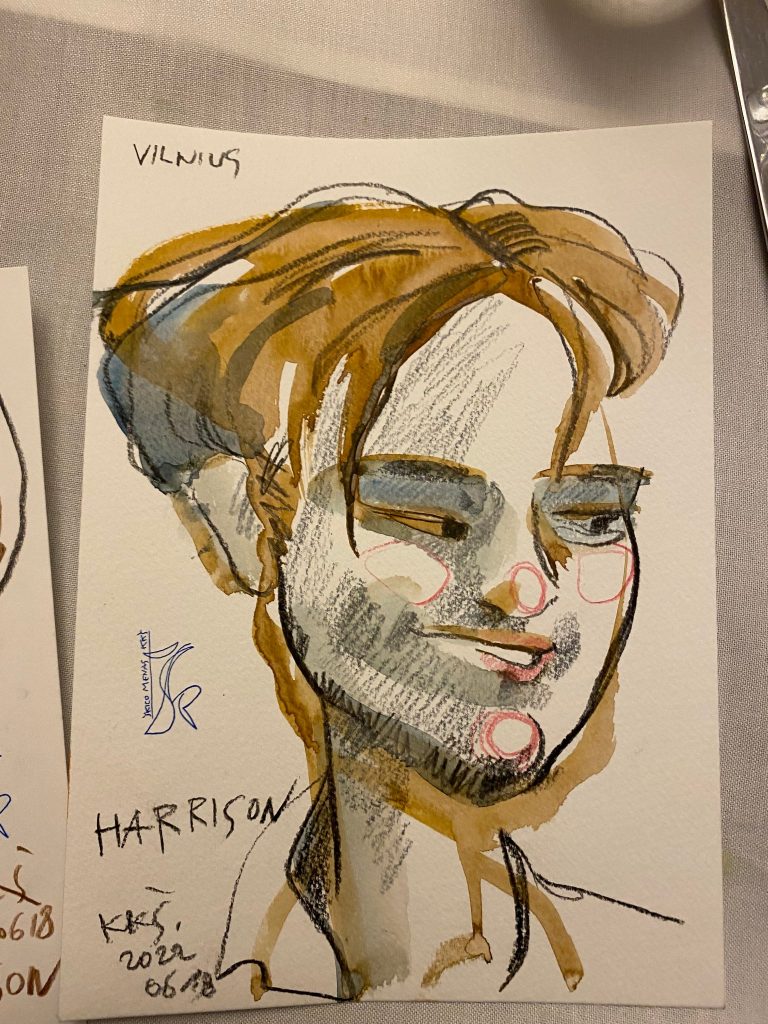

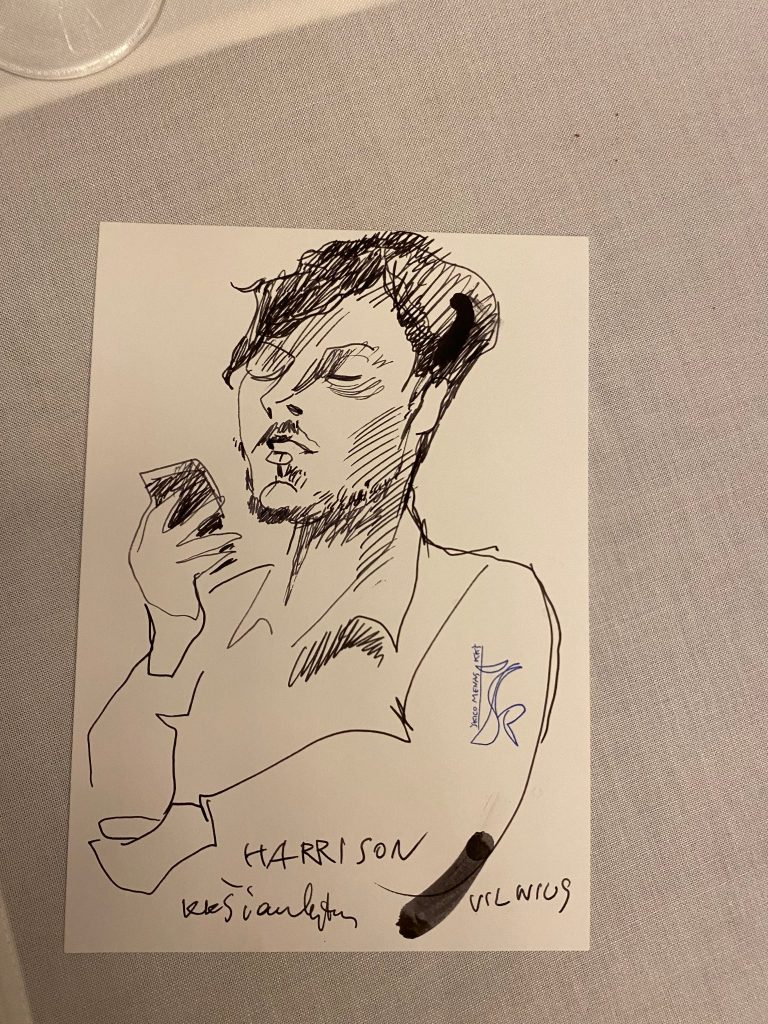

Images above: the author as drawn by well-known Lithuanian caricaturist Kazys Kęstutis Šiaulytis.

Harrison Crone is a junior at Miami majoring in Political Science.