By Grace Farrell

In a world riddled with inequality, the Soviet Union attempted to become a beacon of unity and prosperity, emanating fairness and equality for all. Moscow News during World War II created the perception to English-speaking readers that the Soviet people were pieces in a giant puzzle: all had a place, all vital for victory. Contrary to the Nazis and the Western powers, the Soviet Union capitalized on celebrating the individuality of its people, or at least attempted to paint a picture of unity amongst nations. As Stalin proclaimed, “the strength of the Red Army lies in the fact that it has not, nor could it have, any racial hatred for other people.” The war became a unifying force for the entirety of the USSR, highlighting the importance of each ethnicity and Soviet state. By recognizing their accomplishments, Soviet media gave the impression that the people were united in more than friendship, but in fraternity.

The Great Patriotic War was an opportunity to prove to the world that equality flowed from Stalin’s oversight; seemingly “backwards” nations were now portrayed as developed under socialism. In December 1941, Moscow News chose the nation of Uzbekistan to be an exemplar of such successes. Citing friendship as a key factor for success, A. Abdurakhmanov explains, “In the grim days of war…it has been this friendship that has elevated formerly oppressed peoples and has promoted their rapid advance along the path of progress.” Abdurakhmanov reiterated a message of unity and equality, that the bond between nations, the unbreakable friendship of peoples, could be attributed to the USSR. This point is furthered when comparing Uzbekistan under the tsars to the now successful and plentiful Uzbek SSR, claiming that when it was “a backward region of tsarist Russia, Uzbekistan boasted no industry…in Soviet times, however, it has become a thriving republic, an equal member of the closely-knit family of republics of the USSR.” To readers, it may appear that without the guiding hand of Stalin, Uzbekistan would have been trapped in its backwards ways; only with friendship and socialism was progress able to come about.

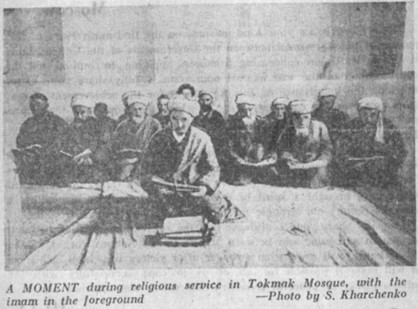

In a time of great conflict, narratives depicting the absolute necessity of unity were crucial to stressing the notion of equality amongst all. One issue from Moscow News in 1943 covers a Kirghiz Muslim and his family’s willingness to fight for the Uzbek SSR. Imam Shakhirhojaev Alim khan-Tyure recounts that he fought against the Nazis because, “the victory of the Germans would mean the loss of all those rights the Soviet state has given us.” His sons were in the Red Army, fighting to protect their new-found freedom. Even though Shakhirhojaev himself was not on the frontlines, he reassured readers that “My heart is at the front…my hope and pride is with my eldest son.” He contributed his greatest gift, his own children, for the Red Army, supporting a war that threatened his new Soviet identity and his own culture. If a Khirgiz Muslim was in favor of the war effort, sending his own sons to the front hundreds of miles away, then surely the Soviet Union was worth fighting for.

The success of Soviet nations was portrayed not just in words on a page, but also through vibrant paintings. One artist, A. Labas, depicted “Uzbekistan in Wartime.” His art, which the story claimed has been featured all over the world, “has succeeded in conveying against the colorful background…that upsurge of patriotic feeling that prevails…in this Central Asian Republic.” He uses “his art to convey the indomitable spirit and boundless energy of these people who are shaping their own destinies.” Through painting, Labas depicted a general sentiment of unity and prosperity of the Uzbek people during the war. The Uzbek people were viewed as significant contributors to the war effort, while also being able to maintain their own lifestyle under Stalin’s rule.

Ethnicities within Soviet states began to be formally studied, to keep up with the façade of equality. The Nganasany people, living on the Taimyr peninsula in Russia, were given a spotlight to reveal how the Soviet government had improved their lives. A Moscow News correspondent, Andrei Popov, examined the nomadic people and concluded that “before the Revolution…the Ngansany were threatened by extinction…by 1917 there were only a few hundred left. None of them had been taught to read or write. Today… schools…have been opened…Medical stations have been set up…They now engage in reindeer raising, eliminating the former threat of famine.” The USSR seemingly gifted the Ngansany people with the opportunity to improve society. As war ravaged the world, the Soviets diligently fought while simultaneously promoting equality against the enemy that advocated for the opposite. Shining a light on the successes of different ethnicities under the USSR gave rose tinted lenses to Soviet ideals, as well as to their valiant cause against Germany.

Despite supposedly cultivating a better quality of life under Soviet rule, it is important to recognize how in this instance, Popov depicted Russia as a civilized savior, unveiling unknown potential from the northern nomads. By completely changing how the Ngansany lived, the Soviet state prioritized what was important to them rather than what was important to the Ngansany; it was implied that Russian living is a superior model, and therefore must be followed.

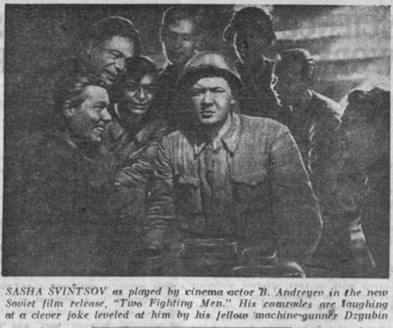

Even if Russia was prized above the others, the façade of brotherhood had to remain strong. Film and music played a significant role in the portrayal of such fraternity. The movie “Buddies,” also known as “Two Soldiers,” was written about in Moscow News as a means of demonstrating the bond between soldiers. Meant to be a window into the frontlines, it explained that “friendships formed on the battlefield between men fighting selflessly for their country is a factor that plays an important role in the war.” While the two characters, from vastly different backgrounds, one a metal worker from Odessa and one a Urals smith, “they are drawn together by the common goal for which they are fighting.” Haunted by the war, the USSR wanted to convey that unity brings hope, and with hope comes victory. Only together can the Soviet states prevail against the Nazi invaders. By reporting on a movie, Moscow News allowed readers to believe a new narrative, one that binds together people from different backgrounds.

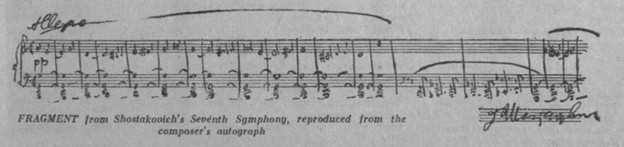

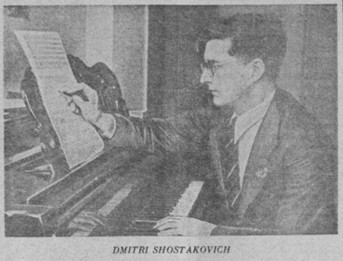

Music was also seen as a commonality that could motivate all states. The prominent composer Dmitri Shostakovich was inspired by the siege of Leningrad and wrote his Seventh Symphony in 1941. Serving as a piece with intentions of unification, “the Seventh Symphony is a patriotic piece of music inspired by the composer’s wrath and hatred for fascism, the enemy of mankind.” Music was used as a device to bring together the entirety of the Soviet nation, no matter a person’s background. In fact, “The first movement…is dedicated to the common people ‘who forge our victories and our successes.’” Moscow News used Shostakovich’s music as a national unifier against the Nazis, bringing together the massive USSR for one common cause.

Shostakovich continued to write symphonies throughout the war, music that depicted siege, victory, and hope. His pieces served as a constant reminder that there cannot be victory without unity. As the symphony began to be performed across the country, it became “evidence…that in spite of the exigencies of war, Soviet composers are given every opportunity to pursue their creative activity.” In fact, it “confirms our belief in the power of progress and culture. With the composer we believe in the great forces of progressive mankind, which will defeat fascism.” Composing in the midst of war reaffirmed what the Soviet Union was trying to portray: prosperity and unity, appreciation for all peoples. By showcasing Shostakovich’s work, the superiority of the socialist system was on display, proving to readers that although war was ravaging around them, the USSR was able to not just survive but flourish.

In the midst of the bloodiest war the world has ever seen, the Soviet Union deemed equality as a vital ideal in Moscow News and other propaganda outlets as a way to contradict Nazi ideology while simultaneously demonstrating the superiority of Soviet ideals. Readers may have seen the USSR in a new light, one of equality and inclusivity. During a time that condemned other peoples, not daring to view them all as equal, the Soviet Union presented an unheard of perspective: recognizing differences can unite.

References:

Abdurakhmanov, A. (1941, December 29). Uzbekistan Redoubles Efforts to Secure Victory Over Nazism. Moscow News.

Kovsky, E. (1943, June 14). Kirghiz Moslems Fight Hitler. Moscow News.

Moscow News Correspondent. (1944, January 26). Study Nganasany, World’s Most Northern Nationality. Moscow News.

Ogolevets, A. (1941, December 29). Shostakovich Completes His Seventh Symphony . Moscow News.

Ogolevets, A. (1942, March 10). Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony Scores Merited Triumph. Moscow News.

Rovich, H. (1943, September 29). “Buddies” Is Good War Film About Friendship Formed During Fight for Common Goal. Moscow News.

Stalin, J. (1942, February 24). Order of the Day of the People’s Commissar of Defense. Moscow News.

Varshavsky, L. (1944, April 5). Artist Portrays Central Asia at War. Moscow News.