By Zach Golder

Since the collapse of communism, scholars have argued that civil society is lacking in Eastern European countries. These nations have consequently been viewed as sources of corruption and rent-seeking elitism. From an academic perspective, this was a surprising development considering the wealth of civil society connections leading up to the collapse of communism in 1989. Dr. Sabina Pavlovska-Hilaiel addresses this concept in her 20 February lecture at Miami, mainly focusing on the role of civil society in post-communist states, and concludes the situation in Eastern Europe is more complex than most academics assume. Her main argument stems from the question of why progressive institutions in Eastern Europe were thriving until 1989 but weakened by the late 1990’s, as well as the role civil society played in the transition. Her research not only presents a better way to consider civil society as a whole, but also the European Union’s role in nurturing democratic institutions in formerly communist states.

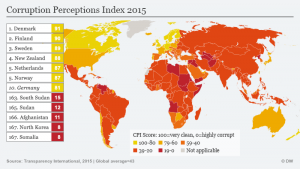

Pavlovska-Hilaiel’s research principally revolves around the issue of corruption in Eastern European nations. She first notes how in general corruption has been on the rise, as opposed to the west where corruption has stayed at relatively the same level. In order to determine how to address corruption and identify its causes, she next raises the question of normative change. A key feature of normative change is determining ownership of reforms, in which civil society plays a prominent role. It serves to first monitor the state, second connect citizens to political elites, and third to create a public dialogue between citizens and government entities. In short, it represents the ability of citizens to unite and engage with issues that directly relate to them. Pavlovska-Hilaiel limits her study to three subjects: Bulgaria, Georgia, and Montenegro. Her findings show that despite the broad characterization of these nations as increasingly corrupt, their experiences vary in relation to each other. Such variations are determined by national circumstances, as well as when and to what degree the European Union chose to intervene.

In order to convey the complexities of civil society in Eastern Europe, Pavlovska-Hilaiel utilizes a “social network analysis.” The aim of this model is to measure the strength of any civil society network by ascertaining a broad analysis of non-governmental organizations (NGO’s) and taking their influence with the government and citizens into account. From this data, she was able to project the strength of civil societies for her three subjects. After calculating that data, she cross-referenced it against European Union partnerships with NGO’s in the three nations. The results point to three nations with very different experiences based on the amount of civil society activity, EU involvement, and the timing of EU involvement.

Despite some minor concerns regarding missing or difficult to discern data, Pavlovska-Hilaiel’s research supports her conclusions. Her assertions that the three subject nations had different experiences and were directly affected by the EU’s partnership with NGO’s from the early 2000’s to the contemporary era represent a more nuanced way to consider post-communist Eastern Europe. There are some issues, however, regarding gaps in the data analysis, as well as methodological approach. Her analysis of Montenegro, for instance, stood out because it did not contain any data from 2003 or 2007, putting it in stark contrast to the other subjects. The 2013 data on Montenegro proved sufficient for determining the EU’s cooperation with NGO’s, but without the progression data, important conclusions about the intensity and duration of EU involvement are less conclusive. This is particularly critical for Montenegro, considering its more exalted status as a state attuned to pressure application on the government for the purposes of affecting change. Some of Pavlovska-Hilaiel’s methodological approaches also could have been more clearly explained. In introducing her social network analysis, she did not go into much detail about how the influence of NGO’s and individual actors were calculated for her study. Consequently, her findings should be considered with a healthy amount of scrutiny. As for the originality of her argument, our readings in class, most notably the piece by Ekiert and Foa, point to increased academic scrutiny on the subject in recent years. Pavlovska-Hilaiel’s argument is unique because it focuses on Bulgaria, Georgia, and Montenegro, but the assertion that the Eastern European civil societies are more complex than older studies assume is not a new concept.

If we assume that the problematic aspects of data collection are easily remedied, what then are the implications of this study? Again, the idea that East European civil societies are more complex than previous assumed is not a new concept, but how would these three states in particular fit in to the broader work of European civil society and the EU? Whether these represent exceptional or typical examples could be the next step in a broader study of post-communist Europe. This begs the question of whether a broad study of Eastern Europe is even possible, considering the diversity of the continent. If we are to assume each state has its own distinctly unique civil society, however, it would be important to consider how their history or cultural tendencies possibly played a role in state development. Ultimately, the methods and applications of Pavlovska-Hilaiel’s study are debatable, but her research is undeniably still a boon for the field of European post-communist studies.

Zach Golder is a second-year MA student in History.