By Ashlynn Galligher

Note: this is the second of several articles posted to The New Contemporary that feature writing from this Fall’s Havighurst Colloquium, “Russia in War and Revolution.” Each student in the class had to select an object from the Andre de St.-Rat Collection in Miami’s Special Collections and write about it. These writings, as you will see, spotlight the incredible collections in our library. They also highlight how the Russian Revolutions in 1917 involved a battle over meaning: through these primary sources, one can read the words, see the images, and therefore gain more insight into the experiences of revolution. Other papers have been posted to the History Department’s new online journal, Journeys Into the Past: http://sites.miamioh.edu/hst-journeys/category/essays/. Special thanks to Masha Stepanova, Miami’s extraordinary Slavic Bibliographer.

Bibliographic Source Information: Unknown artist, “Let’s Transform the Coming Imperialist War into a Civil War.” Soviet Power, 1930 (Printed in 1930). Glavit: Moscow. Miami University Special Collections.

In Russia, World War I is thought to have lasted from 1914 to 1917 and the Russian Civil War from 1918 until 1922. Even if we take Peter Holquist’s view that this period is best understood as one “continuum of crisis,”[1] however, these conflicts and memories of them lasted well beyond those time frames in the propaganda posters published by the Soviet Union. One such propaganda poster is “Let’s Transform the Coming Imperialist War into a Civil War.” To understand this poster from the perspective of a Soviet citizen one needs to understand the terminology used an on the poster to comprehend how it was perceived by its audience and what was the greater goal of the poster.

First, the terminology used in the poster harkens back to the two wars that Russia was involved in that led to the creation of the Soviet Union: World War I and the Russian Civil War. These two wars evoke extremely different ideas from Soviet authorities. When World War I broke out in August 1914, Lenin was exiled in Switzerland formulating his his slogan: ‘Transform the Imperialist War into civil war.’”[2] It is quite evident where the poster got its title from in regards to Lenin, but it goes beyond just his slogan. World War I, as explained by the Bolsheviks, was an imperialist war, a war fought for land and power not for the people that lived within the borders of the countries. Imperialism itself, as Lenin famously phrased it, was “the highest stage of capitalism” or “monopoly capitalism.”[3] This bleak outlook on capitalism captures the Bolshevik belief that it was the great evil of the world that destroyed the strength of the working class. By 1930, this would have been a familiar view for any average Soviet citizen viewing the poster.

Additionally, Lenin considered imperialist wars to be the “most criminal of wars [that] drenched the world in blood,”[4] with “Russia’s part a predatory imperialist war owing to the capitalist nature of that government.”[5] This would create a negative connotation of World War I, that it was orchestrated by capitalists that had little care about the carnage that the war created. With the poster calling for preparation for an impending imperialist war, it creates a sense of urgency that society needs to submit all of its efforts into creating a stronger Soviet Union. This call for action aligns perfectly with the First Five Year Plan, for in 1931 Stalin stated that there was a need for rapid industrialization “in ten years. Either we do it, or we shall go under,”[6] to which he was alluding to an impending war against the Soviet Union. These hardened beliefs of imperialism and imperialist wars are foundational concepts for the Soviet Union and for the Soviet experience that citizens would have remembered in 1930.

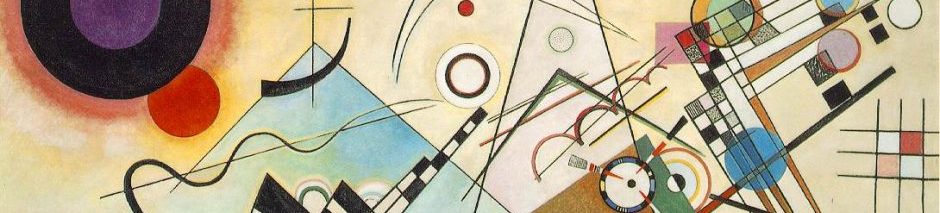

Furthermore, the second part of the poster calls for the transformation of a war that will become a civil war. Why a civil war? This was partially due to the fact that for the Soviet Union to be created it went through World War I directly into the Russian Civil War, with the outcome of the civil war being a Bolshevik victory and subsequent foundation of the Soviet Union in December 1922. Lenin saw civil war as the “only war that is legitimate, just and sacred.”[7] Likewise, in 1922 Lenin said that “the Civil War has welded together the working class and peasantry and this is the guarantee of our invincible strength.”[8] Both of these statements work together to explain the poster: in the Soviet view, imperialist wars are awful, bloody events that should be avoided, but civil wars are hallowed and are the will of the people that unite them against their oppressors. The poster alludes to this staunch differentiation of the wars to remind Soviet citizens that they need to be prepared for a coming imperialist war so as to help their brethren of the world throw off the yoke of oppression and embrace communism as they have. This coincides with the images on poster as there are three men holding a red flag, the color of the Bolsheviks, marching towards what appears to be the coming imperialist war. This iconography demonstrates the bringing of the civil war to the imperialist war, as it was the Bolsheviks that brought the end of World War I with the immediate replacement of a civil war.

Furthermore, this poster works as propaganda for the Soviet Union as it reaffirms that the Bolsheviks were on the correct side of history and that their warnings and recommendations should be seen as legitimate. The Bolsheviks never wanted to partake in World War I because it was seen as the highest form of capitalism and its whole purpose was to better the empires that were oppressing the working class. In addition to their general dislike of World War I, the Bolsheviks were also the only group that constantly opposed it. This placed the Bolsheviks in a particularly good spot when most tsarist subjects grew disillusioned with the war. This promise by the Bolsheviks to get out of the war was followed with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, and the poster harkens back to this with the continued opposition against wars of imperialism, even those that will happen in the future.

In conclusion, the “Let’s Transform the Impending Imperialist War to a Civil War” poster was a tool not only of preparation for the future but also an explanation of the past. With Stalin’s desire to speed up the modernization of the Soviet Union, using the promise of another war like the bloody imperialist war would be beneficial. Additionally, the use of Lenin’s original slogan carries the citizen reading the poster, to the original promise of the Bolsheviks and thus allows them to put their full faith into the future. The poster might seem to be completely visual, but the words carry the true weight of the message.

Works Cited

Daly, Jonathan, and Leonid Trofimov. Russia in War and Revolution, 1914-1922: A Documentary History. Hackett, 2009.

Getzler, Israel. “Lenin’s Conception of Revolution As Civil War.” The Slavonic and East European Review (Modern Humanities Research Association) 73, no. 3 (July 1996): 464-472.

Lenin and the First Communist Revolutions, III. http://econfaculty.gmu.edu/bcaplan/museum/his1c.htm (accessed December 7, 2016).

Mawdsley, Evan. The Stalin Years: The Soviet Union 1929-1953. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2004.

[1] Peter Holquist, Making War, Forging Revolution: Russia’s Continuum of Crisis, 1914-1921 (Harvard University Press, 2002).

[2] See V. I. Lenin, “On the Slogan to Transform the Imperialist War into a Civil War”: https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1914/sep/00.htm.

[3] Daly, Jonathan, and Leonid Trofimov. Russia in War and Revolution, 1914-1922: A Documentary History. Hackett, 2009. Pg. 14.

[4] Ibid., pg. 147.

[5] Ibid., pg. 71.

[6] Mawdsley, Evan. The Stalin Years: The Soviet Union 1929-1953. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2004.

[7] Daly, Jonathan, and Leonid Trofimov. Russia in War and Revolution, 1914-1922: A Documentary History, pg. 238.

[8] Getzler, Israel. “Lenin’s Conception of Revolution As Civil War.” The Slavonic and East European Review (Modern Humanities Research Association) 73, no. 3 (July 1996): 464-472. Pg. 465.

Ashlynn Galligher is a senior REEES major.