By Helen McHenry

This past Tuesday, November 6, the Havighurst Center for Russian and Post-Soviet Studies ended its fall lecture series with a joint event between the Humanities Center and the Department of Journalism, Film, and Media. Masha Gessen, an author, journalist, and activist, was invited to speak on the relationship between truth and power in Russia.

Gessen’s lecture compared the tactics of Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, arguing that both leaders aim to create a culture of disinformation meant to confuse and therefore subvert the truth. One of the main tenets of the talk was a theme shared by her recent book, Words Will Break Cement: The Passion of Pussy Riot. Both discuss the “language of lies” left over from the Soviet period through which both Trump and Putin frame their assault on truth, thereby enhancing their own power.

To start, an explanation is needed of what a “language of lies” really is, a term Gessen briefly explains in Words Will Break Cement. Gessen explains that “in all societies, public rhetoric involves some measure of lying,” with history as the successes made in confronting that lie. In societies such as the Soviet Union, however, the lie overtakes the entire public sphere, preventing anyone from speaking the truth without punishment. Therefore, public conversation is an application in “using words to mean their opposites,” a phenomenon analyzed in depth during the lecture.

Although the Soviet Union has now fallen, this language of lies is still alive and well in today’s Russia. Used not only in communication among Russian civilians but as a tool of Soviet propaganda, it has been adopted by Putin to disparage journalism while augmenting his own power. The simplest example of this practice and how it has evolved came from Gessen’s recounting of the Soviet government’s phrase for elections – a “free expression of citizen will.” However, as there was only ever one candidate from which to pick, these elections were neither free nor expressive. The current political system has been dubbed a “sovereign democracy,” meaning in practice that the government is able to interpret “democracy” however it pleases.

This tactic is part of Putin’s larger strategy to assert his power over Russia and the global community. Through his custom of making obviously false claims, such as refuting the presence of Russian troops in Ukraine following the 2014 Crimean invasion, he affirms his right to say whatever he wants. Additionally, he will also reverse a claim for the same reason, as when he later said, “of course there are Russian troops in Ukraine.” This approach keeps journalists and civilians alike reeling as they try and uncover the truth.

Gessen mentioned in her lecture that Pussy Riot “confronts a language of lies,” a process which she studied in detail with her recent book. Words Will Break Cement: The Passion of Pussy Riot follows the lives of members Nadya Tolokonnikova, Yekaterina Samutsevich, and Maria Alyokhina. Put on trial after their performance of a “punk prayer” in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, the book illustrates their arrest and the international outcry it generated.

However, Pussy Riot’s importance in this narrative of the language of lies starts much earlier. In the mid-1990s, Tolokonnikova had the opportunity to witness a performance by artist Dmitry Alexandrovich Prigov. According to Gessen, he took “turgid Soviet language” (the original language of lies) and “molded it” in order to create critical poetry about the modern age. Inspired to performance art, Tolokonnikova soon formed a group with husband Petya Verzilov and a few of their friends, naming it Voina, the Russian word for “war.”

While heavily influenced by Prigov – one of their earliest actions was a video titled The Wake in remembrance of his death – Voina had a slightly different and more challenging goal. The language of lies cultivated under the Soviet Union had already been confronted by dissidents before Voina’s time. Since then, however, this language has been reformed, thereby “discrediting the language of confrontation itself,” as Gessen writes. Voina sought to confront and expose the lies present in their daily lives without a solid foundation of how to express their ideas. Simply put by Gessen, “there were no words left.”

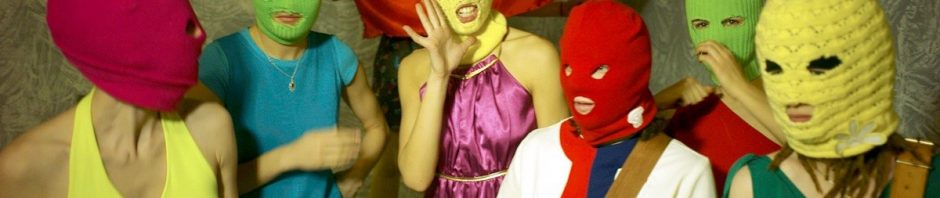

Picture courtesy of boundary 2.

Nevertheless, even after Voina disbanded, Tolokonnikova continued gathering like-minded individuals together to stage protest art. By the time she was invited to present at a conference for Russian opposition groups in 2011, her following included a number of women that began calling themselves Pisya Riot, or Pussy Riot. Performing in various locations leading up to the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, including the Moscow Metro and Red Square, the group has gained international recognition for their colorful dresses and balaclavas. Their politically-charged lyrics continue to attack the unjustness they see every day, from LGBT and women’s rights to the chronic entrenchment of Putin and his cronies.

Picture courtesy of YouTube.

Even as groups such as Pussy Riot confront the language of lies embedded in Putin’s Russia, similarly disturbing trends are being witnessed here in the United States. Like Putin, Gessen argues, Trump lies in order to assert power. The believability of the lie – such as his claims regarding the size of the crowds at his inauguration – is not of importance. The real emphasis lies in the fact that he continues to say what he pleases, which forces listeners to take into account what he says, even if they do not believe it. Over time, this atmosphere of disinformation has seeped into our reality and fundamentally changed the nature of “shared reality,” in Gessen’s words. Only through awareness of these disquieting patterns can we hope to begin to reverse them.

For more information on Masha Gessen’s visit, please see Emily Erdmann’s or August Hagemann’s pieces on the topic. Gessen’s lecture officially concludes the Havighurst Center’s 2018 fall lecture series on Truth and Power. Throughout the semester, we have heard from Anna Veduta of Meduza Media, author Mikhail Zygar, and now Masha Gessen, providing a rich and varied perspective on the Russian media landscape.

Although each reflected a rather dire outlook, none was without hope. In Gessen’s case, her “silver lining,” as she put it, is that these trends may lead to a larger discussion of why we place our trust in a “profit-making enterprise.” She believes restructuring the media into a public utility paid for through taxes or subscriptions may be the key. For now, however, we will have to work within the system as is. But Pussy Riot’s actions and influence have shown us that change is possible – as Russian author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn once wrote, “words will break cement.”

Helen McHenry is a sophomore majoring in International Studies and REEES.