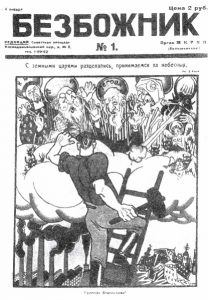

Dmitry Moor, cover image for the first issue of Bezhbozhnik [The Atheist]

By August Hagemann

A picture is worth a thousand words. What exactly those words are varies as wildly as the pictures themselves vary – sometime it’s about emotion, sometimes it’s about experience, and sometimes it’s an ideological argument. The ideological images in early Soviet Russia, specifically those tackling the touchy subject of religion, were the subject of the lecture given by Smith College’s Dr. Vera Shevzov, hosted at Miami University by the Havighurst Center and the Department of Comparative Religion on Friday, March 10th.

Though Shevzov’s interest in the Soviet Union is wide-ranging, her latest research seeks to answer to what extent Bolshevik antireligious propaganda may have had an impact on the Russian Orthodox faith in the present day. Russian Orthodoxy is a religion profoundly different from other Christian denominations, and even from other Orthodox churches, and Shevzov believes decades of vitriolic Soviet propaganda may have had a direct hand in this, steadily undermining the authority of the Church in Russia.

Shevzov opened her presentation by showing the cover of a radical atheist magazine in print in the Soviet Union in the early 1920’s, Bezbozhnik. Illustrated by the prolific Soviet propagandist Dmitri Moor, it depicts a working man with a hammer, a standard archetype representing the proletariat, storming the heavens, populated by terrified, cartoonish representatives of the religions of the world. Below the picture is a caption in which this proletarian man asks the gods’ blessing in his effort to tear down religion. The crux of this drawing was mockery – it sought to take the language of prayer, and use it against those who pray. Shevzov argued that this mission to attack what she calls the “lived Orthodox faith”, the daily experiences and rituals of Orthodox believers, was the primary goal of much early Bolshevik anti-religious efforts.

Of course, this was not the universal approach. Many propagandists attempted to discredit religion through what has been termed the mythological or comparative religion approach. That is, there were attempts to show that the “unique” and “holy” aspects of Christianity – the virgin birth, the resurrection, and other such central tenets – could be find in other, older religions from around the world.

In other cases, the institutions of Orthodoxy rather than Orthodoxy itself fell under scrutiny. Some images depicted priests as spiders, or as affiliates of the bourgeoisie, and so attempted to show that regardless of what one may believe about Christianity as a whole, the Orthodox Church could not be trusted, and was a counter-revolutionary institution.

Though these propaganda efforts existed, and may have swayed some believers away from Orthodoxy, no line of propaganda had such a direct impact on the very foundations of Orthodoxy as those that made a mockery of the religion, such as the materials included throughout Bezbozhnik. These most virulent propaganda efforts took the language of Orthodox prayer and liturgy and make mockeries of them, affiliating them with the bourgeois, with stupidity, and with backwardness. Shevzov explained that these radical efforts sought to cloud the “mind’s eye” of the religious believer, and make it impossible for them to take their own religion seriously. In other words, these artists wanted Russians to see their propaganda, then go into church, and when they hear the language of the liturgy to think of the propaganda rather than of God, and so become incapable of assuming the mental attitude and posture necessary for genuine spiritual experience. Every aspect of the Orthodox faith, from the Eucharist, to common prayers, even to material in the bible such as the beatitudes, was subject to such ridicule.

That is not to say that every Bolshevik supported such heavy-handed attacks on religion – Shevzov pointed out that party members as powerful as Anatoli Lunacharskii opposed such radicalism, arguing it would only further alienate peasant populations from the Bolshevik platform, and Bezbozhnik was shut down after only a few years of publication. But in a country where much of the population was only nominally Orthodox, sowing seeds of doubt as widely as Bezbozhnik-type propaganda did was enough to seriously bring into question even the most central aspects of living life as an Orthodox Christian in the Soviet Union. Shevzov concluded by saying that though she is still researching later Soviet antireligious propaganda, it is clear that the powerful words screamed from these propaganda pieces are words that continue to haunt Russian Orthodoxy to this day.

August Hagemann is a freshman majoring in Economics and Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies.