By Charlie Fair

Portrait by Johann Jacob Haid

The 17th and 18th centuries were a very unfortunate time to be Irish. A brutal civil war between royalist and parliamentarian forces fought across England, Scotland, and Ireland had weakened the power of the monarchy to a considerable degree, and the later deposition of James II of the House of Stuart had all but destroyed the notion of unrestrained monarchical power on the British Isles. More often than not, the Irish found themselves on the losing side of these conflicts, with Irish Confederates backing the royalists in the English Civil War, as well as later siding with James II and his descendants in their efforts to re-take the thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland. With every royalist and Jacobite (those who supported James and the Stuart dynasty) defeat, harsher crackdowns from London would ensue, seeing further persecution of the Irish and of Catholicism.

Those who took up arms against London found themselves with few options upon defeat. Following James II’s failed attempt to regain his throne through Irish support, the remnants of his battered Jacobite army were faced with two choices – they could either bend the knee to the usurper William of Orange or go into exile to continental Europe, serving the Catholic monarchies there. Scores chose the latter, departing for France where from there they would form Irish brigades and units in the armies of France, Austria, Spain, Poland, and more. One of these exiles who found himself bereft of hearth and home was one Peadar Éamonn de Lása, better known as Peter Lacy.

The Siege of Limerick 1690 by N. Currier

Lacy was 13 when the Williamite war came to Ireland, a scion of a Norman-Irish family with a celebrated history of fighting the English Crown all the way back to the time of Elizabeth I. Despite his age, he served as Lieutenant in the Prince of Wales’ Irish regiment during the Siege of Limerick as the first Jacobite uprising wound down. Though defeated, the Jacobites were able to negotiate a withdrawal to France fully armed, and Lacy departed to France with his older relatives. The Lacys were sent to the meat grinder of Louis XIV’s seemingly endless wars in Germany, Holland, and Italy, where most of the Lacy family would die in battle. Seeking his fortune elsewhere, Lacy departed to Austria to fight in the protracted conflict between the Habsburgs and the Turks, but was again disappointed when shortly after his arrival, peace broke out between the two, leaving Lacy and other exiles consigned to dull peacetime assignments. Seeking fame and fortune, Lacy went with other Irish and German officers of the Austrian army to Russia, where Tsar Peter the Great was preparing to pick a fight with the Kingdom of Sweden.

Unfortunately for Lacy, his first taste of battle in Russian service was the disaster known as the Battle of Narva. Though Peter had continued the work of his predecessors in increasingly westernizing the Russian army, most of the inexperienced Russian regiments buckled beneath Swedish cannon and musket fire. The panicked retreat of the Russian army at Narva had led to a staggering loss of life, and a near decapitation of the Russian officer corps. While a major setback for Peter, this void allowed opportunity for lower-ranking noblemen and foreign officers like Lacy to begin climbing the ranks of the Russian army, an institution long dominated by the more prestigious and ancient Boyar families. Despite slowly but surely climbing the ranks of Russian high society, Lacy famously made no effort to nativize himself, refusing to learn any Cyrillic writing or to abandon his Catholic faith.

The victorious Russian army after the Battle of Poltava, art by Alexander Kotzebue

The pendulum swung back in the Tsar’s favor as the Swedish King Charles XII became bogged down in Poland and Peter was able to chase Swedish forces out of the Northern Baltic. In 1708, the now Colonel Lacy gained fame by humiliating Charles at the Battle of Rumna, running the King out of his own camp. Lacy and the Russian army’s finest hour in the war would come the next year at the Battle of Poltava, where a joint Swedish and Cossack army was soundly defeated by the Russians. Though the war would drag on for another decade, the victory at Poltava would secure Russian ascendency in Northern Europe and accelerate Lacy’s career to unheard of heights.

With the Swedes on the run, Lacy and the rest of the Russian army were set loose on Russia’s mortal enemy – the Ottoman Empire. His service against the Turks rose Lacy to the rank of lieutenant-general, and he spent the remainder of the great and terrible war against Sweden prying Charles XII’s armies from their remaining strongholds in the Baltic.

Tsar Peter would not live long following the end of the Great Northern War in 1721, dying four years later. Lacy by now found himself as one of the most powerful military men in the Russian Empire and became embroiled in the musical chairs of the Romanov dynasty succession. Peter had killed his only healthy son Aleksei, and many powerful candidates circled the Russian throne as Peter lay dying. Eventually, Peter’s second wife Catherine took the throne, and Lacy’s services were called upon to expel one Maurice de Saxe, a French nobleman who had designs on Russian possessions in the Baltic, and perhaps even marrying into the Romanov family through Peter’s daughter Anna, thereby challenging Catherine’s shaky claim to the throne.

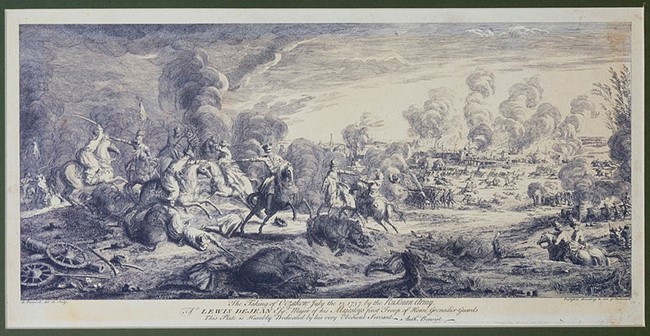

Rescuing Anna from a marriage to de Saxe greatly endeared Lacy to the then Duchess of Courland, and Lacy reaped many rewards after Anna found herself Tsarina of All Russia following the death of Catherine and Peter the Great’s sickly grandson Peter II. Anna relieved Lacy of domestic and intrigue-based tasks and sent him west to fight in the War of Polish Succession. Lacy’s armies took the capital of Warsaw and the critical port city of Gdansk, seating the pro-Russian Augustus III on the Polish throne. Fighting in Poland managed to spill over into yet another conflict between the Russians and the Turks, and our favorite Irishman found himself multi-tasking by 1735, leading Russian armies to expel the Turks from Crimea and Southern Russia. It was here that Lacy formed a bitter rivalry with German-born Marshal von Münnich, and the two campaigned across the Crimean peninsula and beyond to win the Tsarina’s favor. Lacy won out in the end, catching the Turkish armies led by the Crimean Khan in two battles that crippled the Ottoman army. The Ottomans and their Tartar allies in retreat, Lacy’s armies laid waste to the Crimean countryside before laying siege to and taking the fortress of Czivas-Coula (today Chufut-Kale).

Following his rampage through Crimea, Lacy was recalled to the Baltic to govern Russia’s new territories taken from Sweden. Tsarina Anna had died, and another round of promotions and sackings had occurred, among the latter was Lacy’s hated rival von Münnich. The new Tsarina Elizabeth, Peter the Great’s youngest daughter, had sought to clean house from Anna’s favorites, leading to an escalation of anti-foreign (especially anti-German, as Anna had kept many Germans like von Münnich in her inner circle) riots that threw the imperial capital of St. Petersburg into chaos. Lacy won great affections from Elizabeth by putting down the riots with the city’s garrisons, quelling dissent and restoring order, as well as confirming his direct commitment to the new Tsarina. However, Lacy could hardly take a moment’s rest in the Baltic as war had once again broken out between Sweden and Russia. Lacy was given an army and dispatched to drive the Swedes from Finland. Initial successes drove the Swedes away from the closet Russian territories in the North. Though Lacy had struck many a devastating blow against the Swedish army, miscommunication between Lacy and St. Petersburg, as well as the Russian navy being hamstrung by bad weather had stretched his supply lines thin and prevented him from capitalizing on his successes.

Russian and Tartar Cavalry clash at the Siege of Ochakov, by Anik Benoit

Nevertheless, the following year Lacy received his badly needed supplies, and once again marched against the Swedes. The year’s campaigning would culminate at the Finnish capital of Helsinki, where Lacy trapped a Swedish force of 17,000 and bombarded them with artillery and infantry until they finally surrendered. The war would drag on for another year as the Russian and Swedish navies played a game of tug-of-war in the Baltic, but further Swedish defeats as well as Lacy’s forces managing to sneak past the Swedish navy and touch down in Sweden proper saw the country sue for peace with Russia in 1743. The resulting Treaty of Åbo saw Russia carve off chunks of Finland and the few bits of Baltic land Sweden still had after their defeat in the Great Northern War.

After what can be described as an incredibly hectic life of campaigning and soldiering that took him from one end of the world to the other, Lacy finally settled down in the Baltic with his wife Maret von Funcken. They had two sons and five daughters, his younger son Franz going on to become one of the most famed Austrian marshals. Finally, on April 30th, 1752, at the ripe old age of 73, the now Peter Graf von Lacy passed away. His career saw 31 campaigns in every corner of Eastern, Northern, and Southern Europe. Peadar de Lása began his military career as a teenager on the run, in a community of exiles that had few hopes beyond the goodwill of their host countries. At its conclusion, he was Peter von Lacy, Count and Field Marshal of the Russian Empire. While historians must try to avoid speculation and conjecture, it does not seem unreasonable to assume that this Irishman died a very content man.

Charlie Fair is a junior undergraduate fellow at the Havighurst Center majoring in Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies

Suggested Reading

D. P. Graham, The Irish Brigade, 1670 – 1745: The Wild Geese in French Service (Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2019)

James McGee, Sketches of Irish Soldiers in Every Land (NY: 1873)