By Ana Davis

The age of Slavic brotherhood has come to an end. Someone should inform Moscow and Belgrade.

It is June 2, 1848. Intellectuals from nearly every Slavic nation gather in Prague to discuss the future of their peoples at the first Pan-Slav Congress. Some want a clean break from the Habsburg Empire, some simply autonomy. Some desire a united Slavic state ruled by Russia. The conference ends in chaos. An Austrian garrison opens fire on a group of peaceful protesters. The intellectuals go home, disappointed.

It takes another 70 years before these nations see themselves free of Germanic rule, and another 70 after that to gain full independence.

Fast-forward to 2023, and it seems as though Vladimir Putin and Aleksandar Vučić, Presidents of the Russian Federation and the Republic of Serbia, respectively, are unaware of the passage of time, and the changes in geopolitics that have occurred because of it. With their historical alliance remaining strong amid the war in Ukraine, they have promised to coordinate more closely on matters of security and foreign policy. They, along with Belarus, continue to hold their annual “Slavic Brotherhood” military drills as a sign of unity against a NATO alliance intent on breaking up their perceived territorial integrity. And crucially, they both continue to deny the existence of Ukraine and Kosovo as independent nations.

Frighteningly, Serbia seems to be doubling down on its support of Russia. The streets of Belgrade have in the last year frequently filled up with protesters applauding Putin’s efforts in Ukraine, while the sides of buildings display murals dedicated to the Russian President, or the “Z” symbol now synonymous with support for Russia in the war. These same images can be seen on mugs, T-shirts and magnets sold in souvenir shops, or on the front pages of populist magazines.

One word permeates all these propagandistic messages: “braće,” or “brothers” in English. It speaks to the widely-held sentiment among the Serbian population that Russians and Serbians share a deep cultural bond, rooted in the common heritage of the Slavic people. Indeed, neither country seems capable of accepting that Slavs have dispersed and created new national identities that differ greatly from one another. Both their national myths rely heavily on portraying themselves as the grand unifiers of long-lost brother-nations. Russia aims to restore the territorial and national boundaries of Kievan-Rus’, while Serbia insists that Kosovo is the birthplace of ethnic Serbs. Both structure their foreign policy around not contradicting the other in its claims.

But the power dynamic between these countries is clearly unbalanced. Russia does not need Serbian aid. Because of its size and military strength, it can stake its claim to Ukraine without any international support. Serbia, on the other hand, is a far-fetched EU candidate with a stagnating economy and a serious brain-drain problem. It has very little negotiating strength within the alliance. This makes it ripe for exploitation.

Russian soft-power politics in the Balkans haven’t gone unnoticed by observers over the years, but the recent spikes in pro-Russian propaganda and Russian-led covert-operation initiatives in Serbia have made Western experts question Vučić’s ability to say no to the Kremlin. He, along with much of the country, seems to hold the same naïve ideals as the intellectuals that came to Prague in 1848 – that Slavic nations are destined to unite in brotherhood and fend off their Western oppressors. No one from the Serbian delegation seemed concerned with the domestic terrors of then-Tsar Nicholas I, and few Serbs today have anything negative to say about Vladimir Putin.

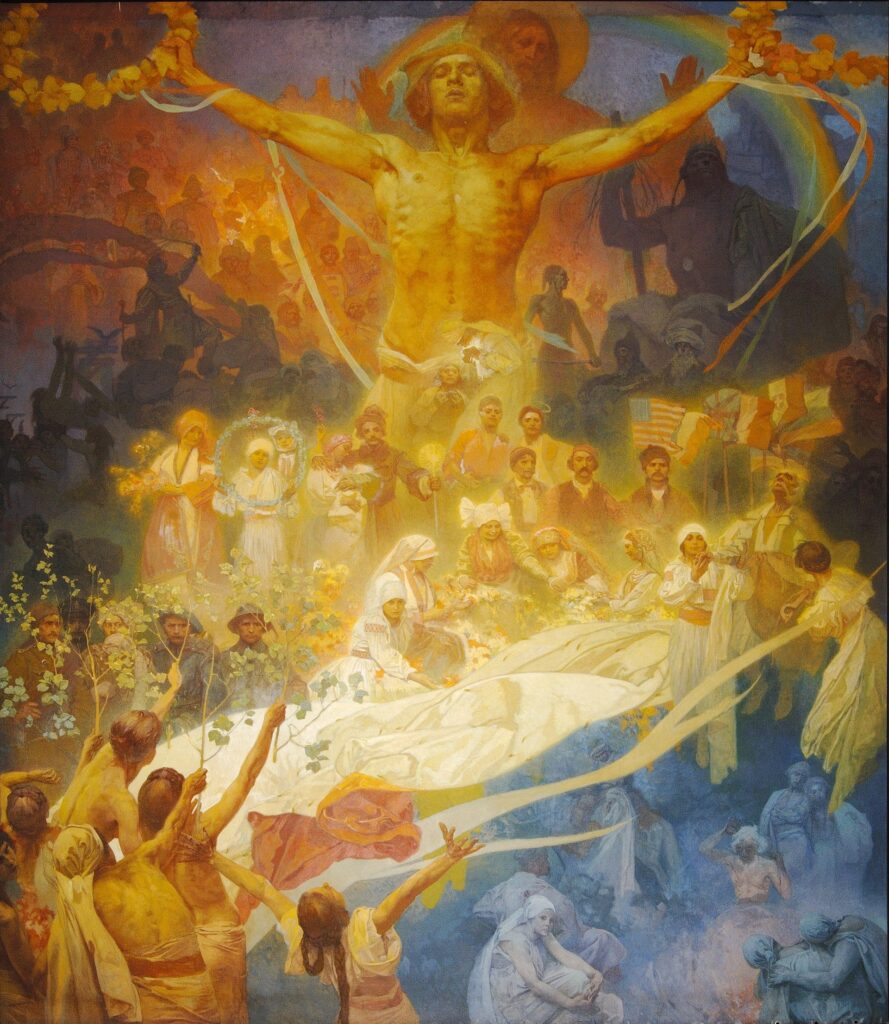

The problem with this version of Pan-Slavism is that it has always relied on a foundational myth to make its case: because Slavs were one people in the past, they ought to be one people now. But what if this was just a legend created by 19th Century historians? Most experts now understand that Slavic tribes were always diverse in their customs, with nothing more than similar languages to unite them. The same is true today – Slavic nations in Europe share a linguistic category, just like the French, Italians, Spanish, and Portuguese. Beyond that, they are modern polities with complex relationships that differ from one policy point to the next. So why do the Serbs continue to romanticize an ideal that was never true in the first place?

Because they, just like the Russians, refuse to deal with the trauma caused by their history. It is easier to blame NATO for your domestic issues than it is to own up to systematic genocide. It is also more convenient to look for a grand savior in Russia than it is to enact the reforms required to build up a functioning national government. But in the end, all ideals meet their disappointing demise without concrete, decisive action. Just ask the Pan-Slav conference-goers.

Ana Davis is a senior majoring in Diplomacy and Global Politics