By Izzy Tice

By the 45th week of 1991, many Russians feared the transition from communism to capitalism, and believed such a rapid change would devastate the economy. Questions about currency and money circulation percolated throughout Soviet society at this time. Nearly every page of this week’s 15-page issue of the Moscow News focuses on money and the unknown future that lay ahead for the Russian economy.

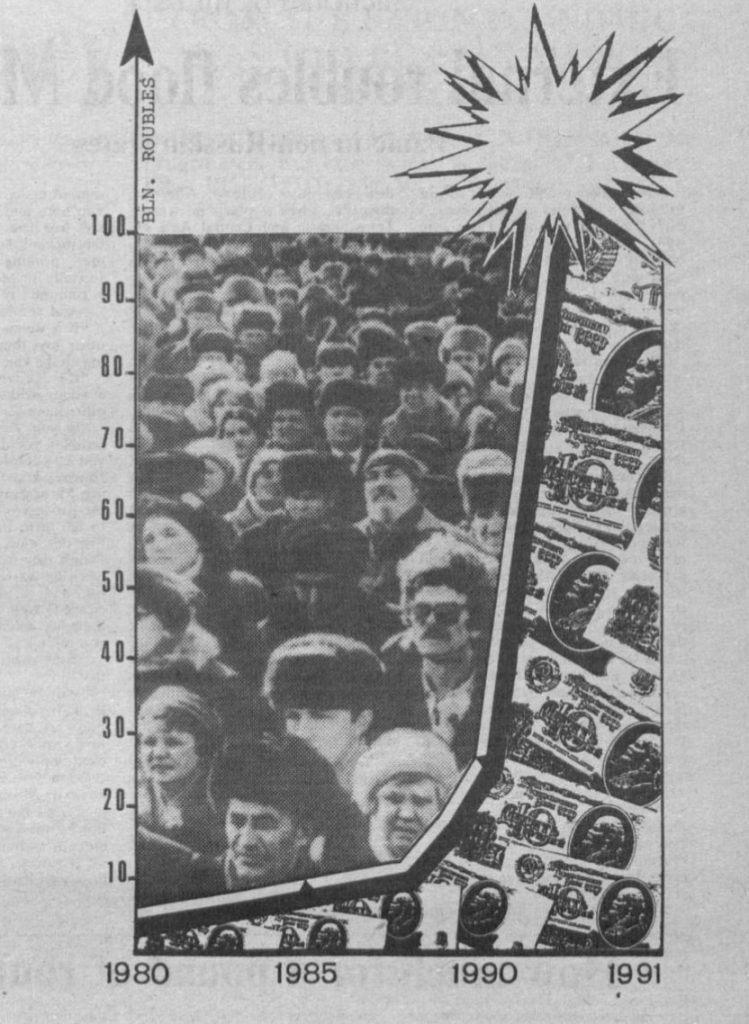

One critic, Vladimir Gurevich, refers to the impending economic disaster as the “Russian Pompeii”, as he voices the popular belief that the “tidal wave” of external rubles into Moscow is all but sinking the economy entirely. In a sense, during this week in 1991, the Russian economy found itself in a sort of grey area, where the transitional period left Soviet currency useless and where people began to resort to bartering. Gurevich even mentions Muscovites paying their cab fares with meals and hot coffee; these things went further in the economy than paper cash. Gurevich makes a subtle but intriguing point, that the Russian government at this point was essentially “thrashing about” to find a means of escaping its own actions, so the economic situation was rather unpredictable with any degree of reasonable certainty.

With some irony, it is interesting to note how self-aware the Russian population was at this time, especially in their open criticism of the government, something not at all possible decades prior. Alexander Fyodorov details his experience in a “hard-currency shop”, a store where both Russians and international visitors use foreign currency to purchase food and alcohol. Fyodorov explains that in accordance with the Criminal Code (which was still in place at the time of this issue), “all operations with foreign currency are the exclusive right of the State Bank.” In other words, such operations were entirely illegal for Russian citizens to be involved in, yet they were essential for people to get food onto their own tables. The store Fyodorov visited was a Soviet-Irish trading company, though one interviewee explained their personal preference for the Finnish department store in a different area because they accepted credit cards, virtually eliminating the infamous queues. While shortages and queues may be most commonly associated with previous Soviet eras, they had appeared again with a vengeance in the Gorbachev era and continued to be ubiquitous as the Soviet Union collapsed in late 1991. The economy somehow kept reverting back to the need for seemingly endless lines in order for people to access the new “free” market.

From this week’s edition of the Moscow News three decades ago, the new Russian economy is presented in an inconvenient, unorganized, and volatile light. The influx of external roubles from the republics, rapid opening of markets, and general disorder of money in circulation made it easy for citizens to criticize and question the future of the new Russian market. Though the economy would experience volatility across the 1990s, in 1991 it had turned almost upside-down for the general population, who struggled to come to terms with the new system. Additionally, the lack of government involvement (or rather, care) further damaged the faith Soviet citizens had held in the new market.

Izzy Tice is a senior majoring in Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies and Geography.

Fyodorov, A. (1991, November 10). Road to Paradise Paved With Credit Cards. Moscow News, p. 2. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

Gurevich, V. (1991, November 10). Only the Dollar Stays Ever Green. Moscow News, pp. 4–5.