By Jessica Baloun

The Nansen passport was the first known travel document made for stateless people. Since its creation in 1922, it has been foundational in the advancement of refugee law. My interest in this topic stems from my work as an International Studies major, where refugee policy is one of the most pressing issues of our time. This question is deeply tied into ideas of belonging and agency, two themes that have been at the heart of this year’s Humanities Center Altman program on migrations.

The case of Russian refugees during the 1920s stands as a catalyst to the Nansen passport, for it witnessed a perfect storm of people fleeing the Revolution and the ongoing Russian Civil War during a period where Europe was still recovering from the Great War and laws for the stateless were nonexistent. Looking at the Soviet relationship with passports and mobility highlights the importance of refugee mobility and identity as dictated by national governments and how the Nansen passport became vital in transforming refugee law.

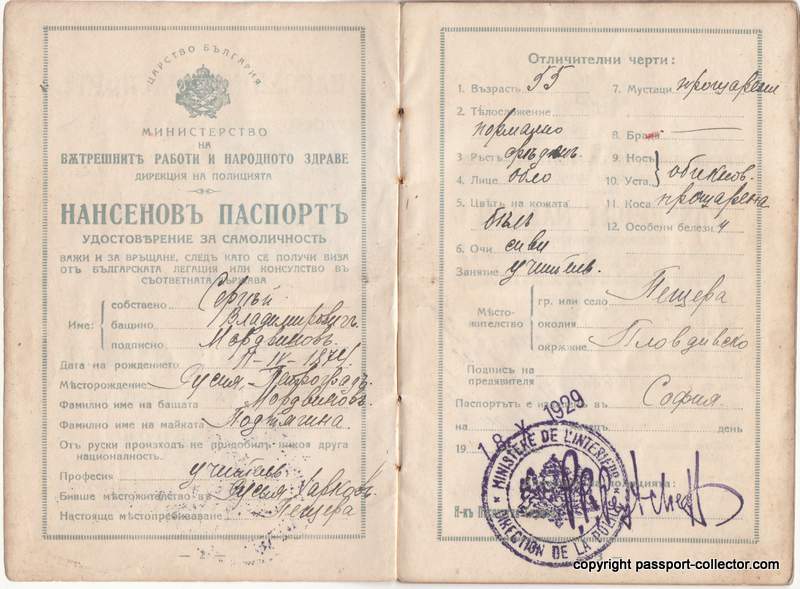

The Nansen passport first appeared under the jurisdiction of the League of Nations in an effort to provide legal protections to refugees fleeing Russia. These passports would serve as legal identification documents in their place of residence and allow for mobility outside of the country. This was an important concept for designers of the passport, as freedom of movement was seen as a fundamental human right but because most people did not live where transnational refugee laws existed or have access to documents, refugees were either stuck in their initial country of refuge or deported to the country they fled. Without identifying documents, these refugees had trouble finding stable work within their host country.

Many member states in the League of Nations saw the refugee problem as temporary so most were unwilling to provide financial support for the adoption of a refugee program. In response, the League appointed Fridtjof Nansen to the position of High Commissioner for Refugees that looked to tackle migratory issues caused by a major famine that was also plaguing Russia.

Nansen was a bit of a celebrity both in his home country of Norway and internationally, having gained fame for his exploration of the North Pole and Greenland as well as his groundbreaking work in both zoology and oceanography. Politically, he was a major advocate of Norway’s independence from Sweden and later received the Nobel Peace Prize for his humanitarian work with the League of Nations. Nansen received it for his work with the Russian famine, but as more and more emigres lost citizenship under new Soviet laws, his humanitarian efforts were forced in a new direction.

Denationalization was a major issue in the wake of the formal creation of the Soviet Union in December 1922, as the new country began revoking citizenship from emigres who had already left. Before this move, citizens were considered stateless de jure, but the decree stripped the former citizens of all protections and for some made them enemies of the state.

Mass population displacement really had no precedent in Russia’s history and only became a salient issue around 1915. The tsarist regime was unable to stop its foes in the Great War from invading the edges of the empire, thus pushing people out of their homes. Nor did the empire really have the capacity to address fully the issues faced by refugees as it was still struggling to fight a total war, the proximate cause of the February 1917 revolution.

The Soviet Russian decree revoking citizenship included persons living abroad for over 5 years, those who left after 1917 without state permission, and those who voluntarily served in anti-Soviet forces or participated in counter-revolutionary activities (which was fairly subjective in the eyes of the courts). Other Soviet republics subsequently enacted similar decrees.

This 1921 decree became the catalyst for action for both the Soviet government and those working on the Nansen passport. This decree set into motion processes of denaturalization for those currently living abroad. The decree was not necessarily looking to cut ties from all of these emigres–the state actually sent ambassadors to certain countries to provide a way for emigres to file for Soviet citizenship–but with the establishment of the 1924 Soviet constitution, mass denaturalization was more heavily enforced by requiring emigres to physically return to receive citizenship. For most political refugees this simply wasn’t an option because it would likely lead to their imprisonment.

Peace treaties signed between the USSR and its independent newly-independent neighboring states such as Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania also forced many emigres into statelessness. They created a timed deadline for gaining citizenship abroad, which meant that Russian emigres living in these lands were forced to obtain citizenship in their place of temporary residence or return and risk imprisonment.

These peace treaties served a dual purpose for the Soviet government because they helped to stop possible counterrevolutionaries from entering the country while also helping the new country gain recognition as a state within the international community. Countries facing an influx of Russian refugees were more than willing to set up agreements with the Soviet Union in hopes of relieving the burden of extra people following the First World War.

Before these treaties, international law recognized these emigres as Russian foreigners under diplomatic protection by the provisional Russian government rather than stateless people. After the recognition of refugee agreements with the Soviet Union, these Russian emigres no longer had protection and became stateless people forced to choose a home.

Alexander Zhirkevich, a Russian writer and military lawyer said the following about this shift in citizenship policy:

“Before, it was so easy to get out of Russia: I took a foreign passport, collected the necessary amount, dressed more or less decently, and at least [got] to America. And now it’s not the same: to get out of Soviet Russia means to perform a feat, to be sure of the existence of miracles in the world.”

Zhirkevich was never a holder of the Nansen passport, but his experiences moving in and around the Russian soviet gave him first-hand knowledge of what it meant to be in constant precarity.

Despite the new legal roadblocks, through the High Commission on Refugees the League of Nations worked to repatriate thousands of Russians living in Germany, Hungary, and Constantinople who wished to return home voluntarily. Even for those wanting Soviet Russian citizenship, the process was selective. Most members of the Soviet government were completely fine with former writers and activists staying abroad, mostly due to a fear of these former citizens returning and engaging in counterrevolutionary activity. Host countries to these emigres feared the diplomatic repercussions of providing aid to people labeled as potential rebels. In his autobiography, Igor Stravinksy –a holder of the Nansen Passport– said that “everywhere Russians were, one and all, regarded as undesirable, and innumerable difficulties were made whenever they wished to travel from one country to another.” Stravinsky’s words perfectly capture the precariousness of what it meant to be a refugee at this time.

Here is where the Nansen passport became vital in creating international refugee law. The 1921 conference between a handful of League members created a system in which refugees could obtain legal documentation and with it, a sense of agency by allowing them to seek permanent residence and full-time jobs. While the passport didn’t solve all the problems faced by stateless people it did provide a semi-effective organizational body that communicated transnationally. States were able to opt into the program and funds from passport fees were redistributed among refugee camps.

The passport proved durable in the short term: By 1942, it was used in 52 states and had been issued to almost half-a-million stateless people. At the individual level, the passport helped to cement a future for those searching for a safe place to call home. It allowed people such as Marc Chagall, Vladimir Nabokov, and Stravinsky to continue to create their art and share it with the world. The Nansen passport provided a beacon of hope for those who were previously invisible under international law.

Freedom of choice in a moment of precarity is the legacy of the Nansen passport, along with a model that would be utilized under the United Nations for migration relief such as in Hungary in the 1950s. Even more, the passport influenced the development of the modern passport, establishing the need for travel documents as a matter of personal legal agency. While the plight of Soviet emigres brought to light the issues of immigration law, the effects of the Nansen passport continues to be felt today.

Jessica Baloun is a senior majoring in History and International Studies with a minor in Russian.

~~~

References

Otto Hieronymi, “The Nansen Passport: A Tool of Freedom of Movement and of Protection,” Refugee Survey Quarterly 22, no.1 (2003): 36-47.

Peter Gatrell, “War, Refugeedom, Revolution,” Cahiers du Monde russe 58, no. 1/2 (1917): 123-146.

George Ginsberg, “The Soviet Union and the Problem of Refugees and Displaced Persons 1917- 1956,” The American Journal of International Law 51, no.2 (April 1957): 325-361.

Stravinsky, Igor. An Autobiography. United States: Library of Alexandria, 1958.

Natalya Zhirkevich-Podlesskikh, “At Ivan Aivazovsky’s,” Galleria 53, no.4 (2016). https://www.tretyakovgallerymagazine.com/articles/4-2016-53/ivan-aivazovsky

Natalya Zhirkevich-Podlesskikh, “Brief Biography Of A. V. Zhirkevich.” http://nasledie-zhirkevich.ru/biograficheskie-ocherki/kratkaya-biografiya-a-v-zhirkevicha/.