By Nancy Pellegrino

Svetlana Alexeivich won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2015 for her “documentary novels,” which capture “her polyphonic writings, a monument to suffering and courage in our times.” Her first, remarkable work, The Unwomanly Face of War, appeared in 1985 and has recently come out in a new English translation. This essay is a reflection on two chapters from it, namely “Grow up girls… you’re still green” and “I alone came back to mama.” The book is composed of interviews with over 200 women who served as members of the Soviet Red Army during World War Two and stitched together in a symphony of voices that Alexievich calls “a history of the soul.” Growing up in postwar Belarus, Alexeivich realized that the narrative of war stories documented or advertised by the Soviet state were virtually all from a man’s point of view. She sought to give impressions of women immersed in total war through the memories of these female soldiers.

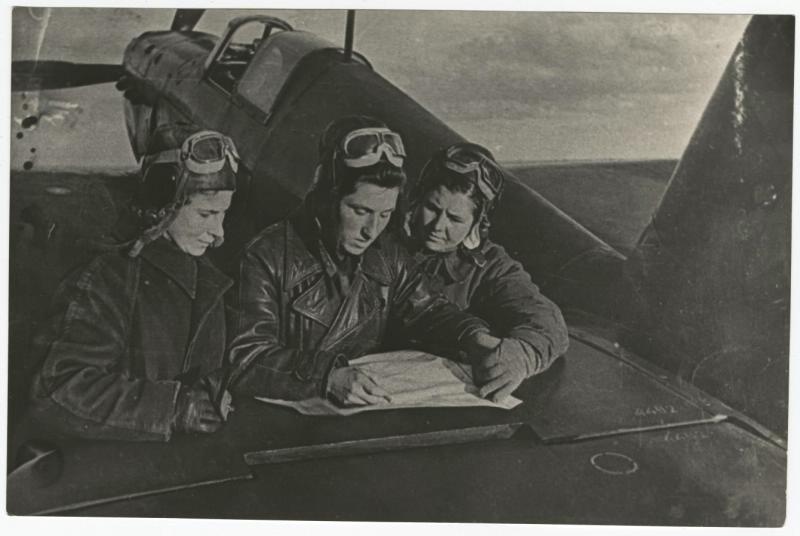

The book provides raw perspectives on experiences unique to women in the armed forces. Empirical data can’t always provide such personal information, and official accounts often ignore them. In the Soviet Union over a million women served in what they call “The Great Patriotic War”, with many in active combat positions. Alexievich’s interviews draw from a wide variety of roles fulfilled by women in the military. These included medical assistants, nurse aides, radio operators, foot soldiers, and anti-aircraft gunners, coming from all ranks- privates, sergeant majors, lieutenants, captains. When responding to the question: “So, in your opinion, women are out of place in war?” one male veteran responded that Russian women throughout history did not just wait at home for the war to be over and gave the example of Princess Yaroslavna pouring melted pitch on the heads of the enemy in the twelfth century.

While women could be recruited, they were not subject to mandatory conscription as the men were. Yet as I have observed throughout my Political Science capstone course that covers the intersections of women and war, women often join the armed forces voluntarily and for the same reasons as men, in this instance- ideology, revenge, and justice. As anti-aircraft gunner Nonna noted, “We dreamed… we wanted to go to war” and Sergeant Major Nina Yakovlevna similarly stated “We had been brought up on the romanticism of the revolution, on ideals,” which instilled in them a drive to participate in wartime efforts to defeat fascism. Not only were the Nazis considered immoral, but the invading German army also killed millions of Soviet citizens and soldiers in 1941. This violence led many widowed, orphaned, or impacted women on a quest for vengeance by means of enlisting. Alexeivich’s interviews reinforce how the motivation for joining truly could be the same in men and women.

Unfortunately, not everyone understood this motivation. After the war, other women would often look down upon female soldiers. One interviewee shared that his wife thinks women joined the army to find husbands and that they all had love affairs, even though her husband describes them as being “honest girls”. Regardless of how “honest” they were, even male soldiers had a somewhat negative disposition towards their female counterparts. When asked if there was love during the war, a male veteran answered, “I met many pretty girls at the front, but we didn’t look at them as women”. All the dirt, lice, death, and ugly nature of the war seemed to corrupt these women in the eyes of male soldiers, who “wanted something beautiful”. Obviously, this opinion is problematic on a number of levels. They were still seen as caretakers, but their sexuality and fertility had been stripped from their identity in the eyes of these men. These women were the ones who saved them, took care of them, and whom they called little sisters. This male interviewee’s statement about viewing female soldiers as sisters also has larger implications for the discourse of women in the armed forces. It combats the idea that the presence of mixed genders will harm group cohesion and insists that women are not simply “distractions”. At the same time, I wonder if this familial role of sisters has anything to do with men not wanting to be vulnerable around their wife and wanting to present as the strong one helping others, not needing help.

The interview with Nina Yakovlevna, who was a Medical Assistant of a Tank Battalion, portrays the dangers women face in war, even if they are not the ones firing a weapon. Nina, standing only 5 feet 3 inches tall, took great offense that only big, strong, and sturdy girls were chosen to be tank medics, but still managed to force her way into the position. Ironically, out of the five tank girls in her unit, the other 4 died, and only Nina survived even though her size meant her comrades thought she would go first. This instance recalls the widespread notion that women decrease military efficacy and reinforced the idea that women had to fit male physical descriptions or desirable attributes, though Nina proved them wrong.

Alexievich’s interviews also show readers how male and female soldiers view the enemy and recall the war. Nina recounted a visit with her friend Vanya, left blind by the war, who regrets only one thing- not being able to destroy just one more German tank. This conversation reveals a juxtaposition between the way some women recall the horrors and suffering of the war and the way some men, even after the fact, still view the war in the context of their duty as soldiers tasked with destroying the enemy. By contrast, anti-aircraft gunner Vera Borisovna laments how dead people whom she has killed haunt her in her sleep. And in a similar capacity, Private Natalya Ivanova, a nurse-aide, shared her experience of breaking off a piece of bread for a young captive German soldier in the dead winter and reflects that she was happy she wasn’t able to hate. Based on the context, it’s clear that the feminization, degradation and destruction of the enemy, which are ingrained in militarized masculinity, did not resonate with most women soldiers.

The concept of the modal man also plagued the Soviet Army, especially when it came to uniforms. Man as the modal worker is essentially the idea that men are the “default” category in organizational structures and that the male body with his male social relations is most desirable for a job; therefore, conditions surrounding the task’s completion will be catered to his form. Any deviation is seen as an accommodation and as a great inconvenience. Two women, Nonna and Sofia, mention the military’s lack of uniforms for women in their interviews. Nonna, like all women soldiers, wore men’s clothes as undergarments and oversized boots until her feet were entirely bloodied and Sofia says that knitted cotton underwear instead of men’s shirts didn’t arrive until the end of the war. And somewhat surprisingly, foot soldier Lola Akhmetova remarks that the worst part of the whole war was having to wear men’s underwear. Several women in the interviews describe themselves as curious girls going to great lengths and breaking rules in order to obtain certain positions in the war or at the front. Women only made up 3% of the entire military force, so it is hard to imagine that the cost of outfitting them properly would have been too great to undertake.

The Soviet Union never included the production of any feminine hygiene products in their central planning, for female soldiers and noncombatants alike. I find it shocking that a nation priding itself on their tenant of gender equality only accounted for men’s needs in terms of planning and production. Scholars also cite positive publicity as a reason for a military’s inclusion of women. While World War II necessitated the Red Army to include women out of need for manpower, I do think they also benefited from this position as it was in line with their official ideology, where Marxism advocated for gender equality and the role of women in the workforce.

Originally written in the 1980s, many of the stories in The Unwomanly Face of War had never been spoken publically because of lingering trauma, the requests of husbands or loved ones, or because of social stigma. These women soldiers–having risked their life for their country–were generally looked down upon as promiscuous by other women or as unsuitable for marriage by men. But Alexeivich worried that this history of women’s participation in the deadliest conflict would be lost by selective history. The Unwomanly Face of War amplifies the voices of female soldiers and gives us an invaluable perspective on their wartime experiences. Ultimately, it’s important to see how these women view themselves as soldiers. Nina Yakovlevna’s poem perfectly captures this topic. Her first lines read: “A brave girl leaps onto the armor plating. And she defends her Motherland. She’s not afraid of bullets or shells-”.

Nancy Pellegrino is a senior majoring in Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies and Political Science. This essay is part of her ongoing capstone research project.