By Duncan Burke

Most everyone tells jokes and there are multitudes of reasons why. Some like to entertain or seek comfort in laughter. Others want to belittle something and mock it. Why then would a national socialist or communist party publish joke magazines? Who are they entertaining, comforting, or mocking? What is their purpose?

In a March virtual visit to Miami University’s Havighurst Center for Russian and Post-Soviet Studies lecture series, Dr. Martha Lampland answered these questions. During her lecture “Why do extremist political parties publish joke magazines,” Lampland argued that these satirical magazines served a vital role for their regimes. Despite the censorship imposed on publishers or by publishers, there was still a great deal of thought and art that was communicated and both Nazis and Communists alike deemed communication an important tool for their power. As Lampland has shown in her research in Hungary, this was a vital tool used in the 1940s by National Socialists and Communists for their expression of power.

Hungary was caught in the middle of the political tensions between the far-right and the far-left in the 1940s, experiencing both fascist and communist rule. The Communist Party had a brief stay of power at the end of the First World War but was soon replaced by right-wing rule. The interwar period witnessed the emergence of several national socialist groups and sectarian tensions. This situation persisted until 1944 when communism returned after the Red Army’s victory in the war. While never existing together, each of these periods of either far-right or far-left rule published satirical magazines. The national socialists published Steel Brush and the communists Ludas Matyi, named after the protagonist in a famous Hungarian poem. While they never competed for readers, their ideals and representations were decidedly at odds.

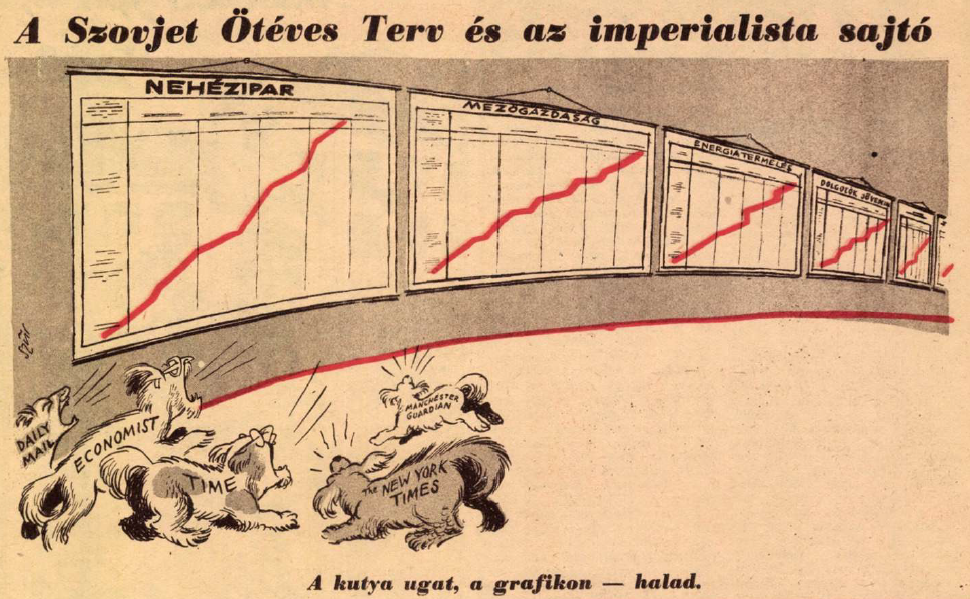

Steel Brush and Ludas Matyi both embodied their respective ideologies in ways many would expect. The fascist publication turned to anti-Semitism to mock Jewish populations and the communist magazine mocked capitalism and the economic elite as well as the fascists. Despite the vast difference in their beliefs and the outright hatred they had for each other, these magazines existed and were created for much the same purpose. Both magazines satirized what they viewed as problems. Their articles and images proposed future solutions through their respective ideological lenses. Readers of Ludas Mayti would see caricatures of the bourgeois hording their wealth and then the strong worker, with plow in hand, who had seized the land and achieved communism. The readers of the Steel Brush would see the caricatures of Jewish people engaged in stereotyped behaviors and uniformed men hauling them to camps. These magazines served as tools of the regime to build their ideologies through satire and sought to provide meaning to readers.

These magazines and their respective regimes communicated ideas quickly to the public and attempted to explain the world around them. The magazines were critical of certain aspects of Hungarian society and strove to reveal these elements in Hungary. Communists stated they were building a better society and criticized the nepotism of capitalism and black marketeers stockpiling essentials the people needed. The problems seen in life were shown as products of capitalism and the former fascist powers in the eyes of communist satire, problems which communism would fix. The fascists engaged in similar satirical practices. However, jokes did not do the heavy lifting of acting out these ideals; they served as great mobilizers for action. Even today, as seen in the Alt-Right in the United States, humor has been used to subvert criticism while all the while still pushing harmful ideas upon people to find new subscribers. Simple jokes about seemingly mundane issues such as vaccines suddenly undermine entire industries and trust in those professionals. Humor and jokes can have powerful unifying effects, as Hungarian fascists and communists both recognized.

Duncan Burke is finishing his joint BA/MA in Political Science at Miami.