Note: 2020-21 marks the 20th anniversary of the Havighurst Center. One of the ways we will mark this occasion is through a regular “Five Questions With …” series, where we will check in with former colleagues, postdoctoral fellows, and students. In this latest installment, Havighurst Center Director Stephen Norris asked Brigid O’Keeffe five questions. Dr. O’Keeffe was a postdoctoral fellow at the Center in 2008-2009 and is now Associate Professor of History at Brooklyn College.

- You have just completed a new book, a major study of Esperanto and its creator, L.L. Zamenhof. Tell us more about this project, particularly how it helps us understand the late tsarist empire and early Soviet Union.

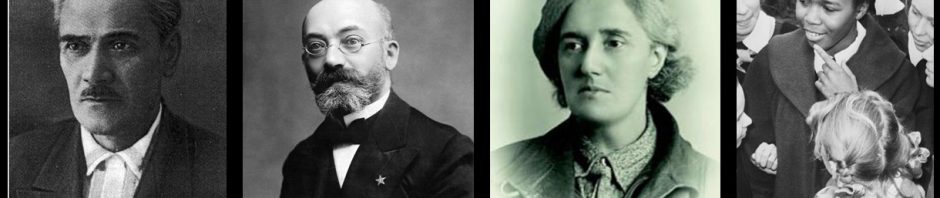

Esperanto and Languages of Internationalism in Revolutionary Russia (Bloomsbury, 2021) is a study of the language politics of fin-de-siecle globalization and the search for a workable international language to unite humankind. Its particular focus is the Esperantists in late imperial and early Soviet Russia who sought to deploy an international auxiliary language to revolutionize Russia and the world. Launched in 1887 from the polyglot western borderlands of a tsarist empire in crisis, Esperanto was designed to give humankind an equitable and effective means of communication. Its creator, L.L. Zamenhof, hoped Esperanto would encourage mutual understanding and harmony among the world’s diverse peoples. Soon after its launch, Zamenhof’s quixotic mission inspired men and women across the globe to learn Esperanto and join in a growing global community of Esperanto speakers. My book is the first to show how Esperanto shaped revolutionary Russia and the language politics of early Soviet internationalism in particular.

The book asks how men and women in revolutionary Russia variously contended with the challenges and opportunities of the evolving relationship between language and international communication in an avowedly global age. It examines how the question of international language and international communication shaped revolutionary Russia’s debates about its – and ordinary people’s – place and role in an interconnected but divided world. I have conceived of it as a contribution to the study of internationalism in modern Russian and Soviet history and of internationalism in modern European history more broadly. I am first and foremost a social historian and so my focus is on the ordinary Russian Esperantists who kickstarted global Esperantist social networks and fashioned global identities for themselves. I also explain how revolutionary Russia’s previously unstudied engagement of international language politics not only shaped early Soviet internationalism, but also laid an essential foundation for later Soviet approaches to the Cold War contest over superpower language supremacy.

2. You are also hard at work completing a book for the “Russian Shorts” series I co-edit (shameless plug right there), this time on the multiethnic Soviet Union. In many ways it completes a trilogy in your research projects, beginning with your book on the Roma in the USSR and including the Esperanto book. What has fascinated you most about the multiethnic empire and how it has functioned? And what do you hope to say in the short book?

I am super excited and honored to contribute to this book series which is poised to offer expert, engaging, and slim volumes on major topics in Russian history to the field no less than to the wider public. Before I talk about my own contribution to the Russian Shorts series, let me say that I have assigned the first book in the series – Eliot Borenstein’s Pussy Riot: Speaking Punk to Power – to my graduate students this semester and I am really looking forward to our class discussion of it in May.

My interest in the Soviet Union as a multiethnic empire was sparked in graduate school at NYU, where one of my mentors, Jane Burbank, taught amazing courses on comparative empires. Jane’s own research, of course, was pivotal to “revisioning” the field toward nuanced study of the multiethnic dimensions of imperial Russian rule and culture – no less than to rethinking and reframing the comparative study of empires in world history more broadly.

My first book (New Soviet Gypsies) gave me the opportunity to focus on Roma’s experiences in early Soviet Union as a means of investigating the lived experience and agency of ethnic minorities as they mobilized and engaged the Bolsheviks’ nationality policy. The book I am writing as a contribution to the Russian Shorts series allows me to widen my scope and chronology but also to communicate to a wider audience why and how ethnicity mattered in the lives of Soviet citizens for the duration of the so-called Soviet experiment. I consider the book I am working on as a testament, as well, to the many insights that can now be found in the still growing scholarly literature on the nature and experience of the Soviet Union as a multiethnic empire. In truth, the reason I am able to write the book at all is because so many talented historians have produced such excellent studies of Soviet nationality policy and of the experiences of different ethnic groups in different eras throughout Soviet history.

The Multiethnic Soviet Union and its Demise aims to provide a concise explanation of the policies and ideological principles that shaped the Soviet Union as a multiethnic empire and that helped determine its fatal fracturing along national lines in 1991. It will explain how and why the Bolsheviks inscribed ethnic difference into the bedrock of the Soviet Union. With a focus on individual life stories, it will illuminate the diverse experiences of the non-Russian peoples of the Soviet Union. Ukrainians and Georgians, Jews and Roma, Chechens and Poles, Kazakhs and Uzbeks— these and many other minority groups all distinctively shaped and were shaped by the Soviet politics of ethnic difference. I am writing this book so that all kinds of readers can understand why and how ethnicity is fundamental to understanding Soviet history and its afterlives.

3. You are moving to different research topics these days, writing about Ivy Litvinov and Huldah Clark, two very different subjects and two very interesting ones. Tell us more, specifically how you found these two and what they tell us about the shifts in your research.

In my research and writing, I have been drawn time and again to the study of people who have been routinely ignored by historians. As time goes on, I realize more and more that what I love most of all is to study the lives of people whose personal biographies are as inherently fascinating as they are revelatory of insights into much larger dynamics in Russian and Soviet history. In recent years, I have been especially drawn to think more often and more intensely about the question of race in Russian and Soviet history. Likewise, I feel especially motivated and energized to shine spotlights on women whose stories have not yet been told or whose stories have not yet been given their due. Historians, too, evolve with their times. For me, living through recent history has left me with a feeling of profound urgency to tend to these questions as best as I can.

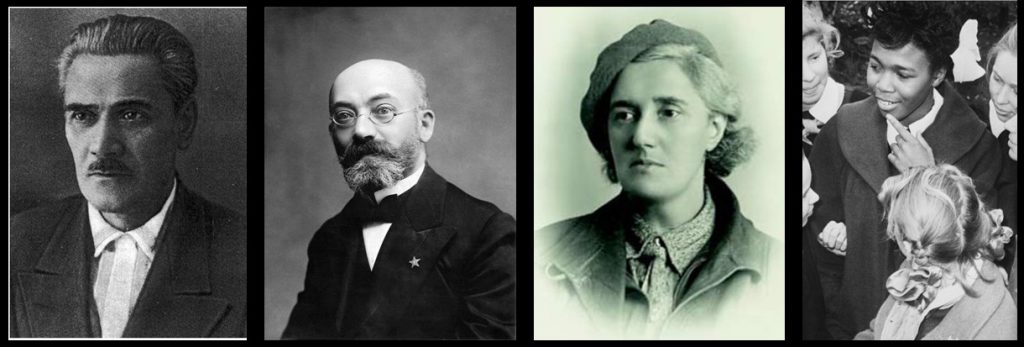

Ivy Litvinov’s personality was outsized. When I began reading the paper trail she left behind, all I wanted to do was read more – to find every scrap of her vibrant and often hilarious correspondence. She first caught my attention when I discovered that she had once gotten into a very raucous public spat with Soviet Esperantists in the 1930s. Once immersed in her archived papers, I realized how much I wanted to place Ivy Litvinov at the center of a very different story – that is to say, the center of her own extraordinary life. Once well-known to the West as the British-born wife of Stalin’s top diplomat in the 1930s, Ivy was much more than Maxim Litvinov’s wife. Ivy Litvinov was a British writer who happened to fatefully marry a Bolshevik while he was living in exile from the tsarist regime. In the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution, she was plunged awkwardly into the role of “Kremlin wife.” Admittedly “bourgeois” and conspicuously foreign-born, Ivy Litvinov nonetheless fashioned herself a “people’s ambassadress” who – when called upon to do so – spoke effectively to the Anglophone West on behalf of the Soviet Union in a language it could understand. But I am equally fascinated by her “public role” as a “Kremlin wife” as I am by her private struggles as a foreign-born woman navigating a rather singular and often precarious fate in the Soviet Union all while pursuing her own ambitions as a writer of English-language fiction. My research on Huldah Clark has only recently begun. In summer 2020, I stumbled upon a photograph of a Black American teenager who was offered a scholarship by Nikita Khrushchev to study in the Soviet Union. Although constrained by the circumstances of the pandemic, I’ve discovered a powerful story that, I hope, can offer us insight into the racial politics of the Cold War but also inspire us to have some important conversations with our students about the intersections of race in American and Soviet history. Stay tuned!

4. How did you get interested in Russia and the USSR? Or another way to put it: how did someone from Cleveland get hooked on Russia?

My students ask me this question a lot, but they tend to phrase it slightly differently: “How did an O’Keeffe become a historian of Russia and the Soviet Union?” Suburban Ohio is as good a place as any for an O’Keeffe or for anyone else to fall headlong in fascination with Russian history. For me, my interest in Russia began when I was in high school. Although I enjoyed studying history, what I then loved most of all was to read fiction. When I was fifteen or sixteen, I read Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five and it changed my life. How? Well, as I remember it, there’s a character in Slaughterhouse Five who claims that all you need to know about life can be found in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. I took that claim literally. Next thing you know, I was tearing through Dostoevsky and reading as much Russian literature as I could. I was bewildered by all the patronymics but thrilled by these stories from a place I knew so little about. When I arrived at Ohio University as a freshman, one of the first things I did was sign up for a Russian language class. Never underestimate the power of a book or an excellent Russian language teacher to change your life. The pity of all of this from the vantage point of 2021 is that I learned last spring that Ohio University was discontinuing its Russian language program. It strikes me that a pandemic is perhaps the worst time for a university to give in to short-sightedness and to begin collapsing its students’ intellectual and cultural horizons in the name of so-called cost-saving. I still hope that Ohio University will reverse course and return to upholding its mission as institution of higher learning and intellectual inquiry.

5. Finally, you wrote an eloquent account for our professional organization’s publication about life in Brooklyn during the pandemic. Have things changed since the initial wave and if so, how?

Anyone who has ever loved New York City, even if just as a visitor, knows what a vital and special place this is – even when it is suffering. I have heard more aching sirens this year than I ever care to again in my life. But I have also heard my neighborhood erupt with jubilation on a sunny November afternoon during a year of extraordinary anguish – I will never forget the joy of that day. New Yorkers’ legendary creativity and capacity to mobilize to support one another in both mundane and monumental ways never ceases to amaze me. When it makes sense to travel again, I hope everyone who loves NYC even from a distance will make a priority of visiting. Come and pay triple price for handicrafts and souvenirs sold by street vendors; eat the delicious food that is still being served at restaurants that have reimagined themselves on this city’s sidewalks and streets – and be sure to be extra generous with your tips; buy plenty of tickets and go listen to the opera singers who last spring performed for neighbors from their fire escapes or to the musicians who practiced their instruments on street corners and along the waterfront; visit the museums and try out the ones you have never visited before. Spend some time in Brooklyn – it’s beautiful. Have you ever visited historic Green-wood Cemetery or Brooklyn Bridge Park? These are two incredible places that have given me much solace over the past year so I’m somewhat hesitant to tip you off to their beauty and glory, lest they one day become too overcrowded with tourist admirers. What you love about NYC is all still here, still humming, still adapting even under the strain and pain of the circumstances. The best of celebrations is yet to come.