By Izzy Tice

A sign of blessing and grace, crossing oneself is one of the most important acts of the

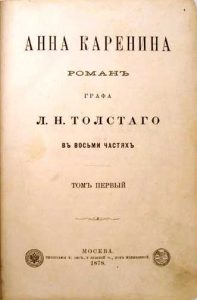

Christian religion, demonstrating faith and belief in God by means of prayer. In Leo Tolstoy’s novel Anna Karenina, Anna’s gesture of crossing herself before her suicide demonstrates the end of the spiritual battle between morality and sin that she experiences throughout the novel, and is paralleled by Levin’s later religious epiphany and faith in God.

Tolstoy depicts Anna’s final sequence as a culminating conflict between the light and

dark of her life, wherein she finds solace and gratification in her call out to God. As Tolstoy

illustrates:

A feeling seized her like that she had experienced when preparing to enter the water in

bathing, and she crossed herself. The familiar gesture…called up a whole series of girlish and childish memories, and suddenly the darkness, that obscured everything for her, broke, and life showed itself to her for an instant with all its bright past joys.

Anna’s flashbacks to her youth and happier memories are representative of her innocence, which has been lost through sin and her struggles with immorality. Through finding her faith in God once again, Anna is able to remember what life had been like before adultery, controversy, and the “darkness” that has consumed her.

In the eyes of God, her death may not be a true suicide, as after she “immediately drop[s]

on her knees,” she realizes the horror of her actions, and pleads to God to “forgive [her]

everything” (695). As Anna feels the “impossibility of struggling,” she is shown as not truly

wanting to end her life at this time; the flame of faith has been reawakened within her and has given her strength to fight, but she is overcome by evil and darkness (695). Tolstoy describes the candle of Anna’s soul as “flar[ing] up with a brighter light than before,” illuminating all of the uncertainties and evils in her life, and then growing dark before it goes “out for ever” (695). Her faith in God has been reignited too late for her to atone and repent for the wrongs she has done in life, but she has become cognizant of the “anxieties, deceptions, grief, and evil” (695) with which she has long-struggled to acknowledge and accept.

At the “literal end” of the novel, the spiritual revelation that Levin undergoes shifts his

views of God from that of needing constant proof of God’s work to an understanding that life is as meaningful as one makes it, without requiring perpetual reminders to have faith (740). Levin’s new faith parallels Anna’s last moments, as if Anna had lived life with full faith in God and with true morals, she may not have felt lost and alone, and could have truly repented and been forgiven of her personal sins. However, by dying before true penance, Anna cannot be completely absolved of sin, and the light of her soul is irrevocably extinguished.

Izzy Tice is a first year majoring in Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies and Political Science.