By Max Jelen

Note: this is the fifth of several articles posted to The New Contemporary that feature writing from this Fall’s Havighurst Colloquium, “Russia in War and Revolution.” Each student in the class had to select an object from the Andre de St.-Rat Collection in Miami’s Special Collections and write about it. These writings, as you will see, spotlight the incredible collections in our library. They also highlight how the Russian Revolutions in 1917 involved a battle over meaning: through these primary sources, one can read the words, see the images, and therefore gain more insight into the experiences of revolution. Other papers have been posted to the History Department’s new online journal, Journeys Into the Past: http://sites.miamioh.edu/hst-journeys/category/essays/. Special thanks to Masha Stepanova, Miami’s extraordinary Slavic Bibliographer.

Polonskiĭ, Vyach. Russkiĭ Revoliutsionnyĭ Plakat. n.p.: [Moskva] : Gos. izd-vo, [1925], 1925.

Polonskiĭ, Vyach. Russian Revolutionary Poster. n.p.: Moscow: State publisher, 1925.

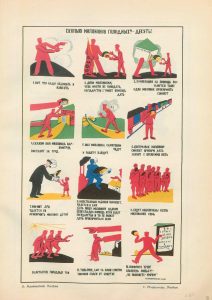

Before delving into any of the content regarding this paper, the reader should be aware that this paper will take the shape of a binary form. The first section will include necessary contextual information, which informs the reader about the origin of ROSTA Windows and the propagandistic they played in Soviet Russia. The second section will include an interpretation of Vladimir Mayakovsky’s ROSTA Window, “How Many Millions of the Hungry?—10!” (see pg 9).

Within the second section, Interpretation: “How Many Millions of the Hungry?–10!” by Vladimir Mayakovsky, a dual perspective will be offered. The first assumes the role of an illiterate Soviet citizen. The basis behind this perspective originates from two notions— first, the fact that I am not fluent in Russian; but second, recognizing that my own lack of Russian language skills makes me not that different from the majority of citizens encountering early Soviet propaganda. Taking this illiterate perspective will primarily involve an aesthetic interpretation of Mayakovsky’s ROSTA Window as it appears prima facie. Then, only after interpreting the aesthetics of the window, I will interpret it from a literate perspective by using an English translation of the text (see pgs 10-12).

The ROSTA Window, which will be subject to interpretation, “How Many Millions of the Hungry?—10!” by Vladimir Mayakovsky, can be found in Vyacheslav Polonskiĭ’s 1925 book, Russian Revolutionary Poster, which includes a collection of posters and other artistic works created by Russian artists during the 1917 Russian Revolution and Civil War. This source, located in Miami’s Special Collections, offers a valuable window into the famous propagandists and their works that would help to define the Bolshevik Revolution.

Russian Futurism and the Emergence of the ROSTA Window

Throughout history, propaganda has been utilized as an instrument to influence the opinions and gain the support of the masses—particularly during times of mobilization, war, and revolution. The utilization of propaganda, notably through the form of posters, can be illustrated through the context of the 1917 Russian Revolution and Civil War. During this period, Russian Futurism also emerged and caught fire with many artists, a style that derived from the works of the Italian intellectual Filippo Tommaso Marinetti.

The premise of Marinetti’s Futurism was rooted in “the destruction of all historical heritage, including museums, libraries and academies of any kind” (Glisic, 356). In his writings, Marinetti references the need for ‘tabula rasa,’ or a ‘blank state’. By this, Marinetti asserts the need for a new start, “on which a new industrial civilisation could grow” (Glisic, 356). Marinetti’s version of Futurism revolved around a movement branded by anarchy, militaristic action, and anti-traditional and anti-bourgeoisie sentiments. Many of the fundamentals on which Marinetti’s Futurism was founded resonated with Russian intellectuals and artists during the early 20th century.

As revolution enveloped Russia during World War I, a faction of Russian artists forged their own version of Futurism—Russian Futurism. Characterized by their avant-garde nature, Russian Futurists sought to merge Marinetti’s tenets with Marxist ideology. This coalescence was achieved by means of “modern artistic production fortified with the state ideology of Communist life-building” (Glisic, 359).

Russian Futurists did not strictly adhere to all of the tenets brought forth by Marinetti. Deviating from some of Marinetti’s notions was necessary in order to mold Futurism with the sensitivities of Russia’s volatile political and social states during the 1917 Revolution and subsequent Civil War. Leading up to, and throughout World War I, patriotic sentiments and actions amongst all social classes coursed throughout the Russian Empire. As seen through the works of Melissa Stockdale and Aaron Retish, mobilization efforts in the Russian Empire leading up to, and during World War I, were met with unwavering support not just from the wealthy, but also from peasants. Despite growing unrest amongst the masses toward the end of the Russian Empire’s involvement in World War I, ideals of patriotism bled into the revolution. However, these patriotic sentiments were premised on Russian culture and nationality—vehemently opposing Tsar Nicholas II and the Imperial Government.

This persistence of patriotic undertones can be seen through the creation and dissemination of ROSTA Windows. In September 1918, the Russian Telegraph Agency (ROSTA) was formed and tasked with the role of delivering news to the people of Soviet Russia. One method by which ROSTA delivered news was through “windows,” which “consisted of four to twelve different frames that told a story, in the style of a lubok” (Bonnell, 199). Lubki (the plurality of lubok) were a popular form of Russian folk print that depicted narratives by means of pictures, which were popular in Russian culture from the late 1600s . The adoption of the lubok style exemplifies a marked fissure between Russian Futurism and Futurism based on Marinetti’s manifesto. Marinetti called for a movement that was anti-traditional, going so far as to call for “the destruction of all historical heritage” (Glisic, 356). In contrast, Russian Futurists utilized traditional heritage through the adoption of the lubok style.

While lubki were used to tell a folk narrative, ROSTA Windows were utilized as an expeditious mode of communication to inform people about ongoing events—oftentimes containing propagandistic undertones. One common theme seen in ROSTA Windows was the binary portrayal of certain groups. Through the use of colors and other symbolic measures, the windows were able to clearly depict the protagonist—in the context of “How Many Millions are Hungry?—10!”, any person or thing colored red—and the enemy—bourgeoisie wore specific clothes (usually a black suit), smoked a cigar, and wore a top hat. The vilification of the bourgeoisie obviously originated from Marxist ideals.

Upon first implementation, one ROSTA Window would include multiple topics or themes, however, through the avant-garde work of Russian Futurist, Vladimir Mayakovsky, “by the end of 1919 [Rosta windows] begun to concentrate upon a single theme treated in a consecutive series of frames in the manner of a comic book” (White, 118). ROSTA Windows, influenced by the traditional lubok form, were short-lived, however—losing relevance by the end of the Civil War. The dynamistic nature of Russian Futurists provides an explanation as to why they were so short lived. Russian Futurists believed that through modern artistic production, they could prepare “the mental readiness of the Russian people to persevere in the process of building this new society after the revolutionary euphoria had been supplanted by the mundane affairs of everyday life” (Glisic, 357). Despite the window’s brief claim to fame and relevance as an instrument of propaganda, they embodied the nature of Russian Futurism and play an important role in revealing the complex political and social state of Soviet Russia during the Civil War through themes of propagandistic undertones.

Interpretation: “How Many Millions of the Hungry?–10!” by Vladimir Mayakovsky (see pg. 9)

There are twelve windows in this particular ROSTA window. From this prima facie perspective, the story begins in the top-left window of the page, following a path—moving down from left to right by row.

In the first window, a man colored red is standing on a hill with smoke in the background. Based on his red color, the man is a Bolshevik. Placing the man on a hill is symbolic of his status—he is placed upon a pedestal and is larger than other Bolsheviks (red colored people) in subsequent windows. As such, it can be surmised that the man in the first window is either a Bolshevik general or high-ranking officer, who is fighting in the Civil War. This interpretation is further reinforced in the second window, where he is holding a flag—signifying his military status. Also in the second window, it appears as though the Bolshevik general or officer is handing a lower-ranking Bolshevik soldier bread or money. It is hard to distinguish between the two. Regardless, the soldier then takes the material goods to a building with red legs. Following the ideals of Marxism-Leninism, the building with red legs can be interpreted as some sort of state owned (Bolshevik owned) building. Moving from the third window to the sixth, the material goods are urgently transported from one Bolshevik entity to the next, all of whom seemingly act with selflessness and in cooperation for a greater cause. In window seven, a large man dressed in a suit with a pipe and top hat appears. This man represents the capitalists, or bourgeoisie. Asserting his dominant role in the hegemonic pyramid of class consciousness, the capitalist strips the material goods from the hands of someone who appears to be a villager or proletariat. In window eight, the capitalist, material goods in hand, stampedes through a village with a Bolshevik factory in the background. Based on windows eight through ten, it is clear the capitalist is greedy and only concerned for himself. Despite the clear wealth disparity between the capitalist and the villagers, he continues to take from the poor and give nothing back. In window eleven, the factory in the background is black—the same color as the capitalist’s suit—representing a capitalist society. A man is then directing a soldier in red to go fight the capitalist.

The addition of the translated text (see pgs 11-12) clarifies the ambiguities that exist to an illiterate person. The title of the poster, “How Many Millions are Hungry?—10!” explains the issue at hand—there are 10 million starving people. As a whole, the poster serves to rally people in the fight against hunger. The first seven windows, with the exception of window five, list government sponsored agencies that are able to help the cause—quantifying how many millions of people each government agency will be able to provide for. After listing which groups and agencies can provide for people, and how much they can provide, window ten explains that three million people will still remain hungry. Upon this calculation, in window eleven a government official urges his “comrade,” who is to be an ordinary man, to save them from their deaths.

Through this visual interpretation of Vladimir Mayakovsky’s, “How Many Millions are Hungry?—10!,” the common Bolshevik propagandistic themes of a bourgeoisie enemy and red-colored protagonist are apparent. Russian Futurists sought to merge the ideals of Marxism and Futurism with the hopes of preserving a successful Communist state. In order to achieve this, they utilized modern artistic productions to “create a new person—person ready to embrace the industrial and technological era ahead” (Glisic, 357). The co-dependent relationship between the masses and the future of Soviet industry is exactly what Vladimir Mayakovsky presents in “How Many Millions are Hungry?—10!”.

Bibliography:

Bonnell, Victoria E. Iconography of Power : Soviet Political Posters Under Lenin and Stalin. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost(accessed December 14, 2016).

Glisic, Iva. “Caffeinated Avant-Garde: Futurism During the Russian Civil War 1917-1921.” Australian Journal Of Politics & History 58, no. 3 (September 2012): 353-366. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed December 14, 2016).

White, Stephen. The Bolshevik Poster. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1989.

Image: “How Many Millions of the Hungry?–10!” by Vladimir Mayakovsky

Translation 1: Russian Revolutionary Poster by Vyach Polonskiĭ

Introduction [page 3]

In the history of the proletarian revolution the poster played a major role. Having developed faster than anything in Europe or overseas, the revolutionary poster is an artistic monument, with which no other epoch can compare.

Born on the street during the revolution, the poster is at the same time a creation of Russian art, and this dual origin makes it even more interesting. A future historian of the revolution, same as an art historian will not be able to avoid chapters about the poster, especially its peak flourishing time during the years of revolution.

Having played a brilliant role during the years of storms and onslaught, the poster however did not exhaust its potential. Its golden age is ahead. We assume, this calls for directing the reader’s attention to its heroic period of development.

We think also that it is with the help of this product of the streets and squares the bonding of art with people will become possible. Not paintings hanging in museums, not book illustrations in the hands of collectors, not frescos, only accessible to some, but the poster and “lubok” — mass-produced, grass-roots, born on the street — will bring art closer to the people, it will show them what can be done with the help of paint and brush, will interest them with its mastery and free the artistic potential dormant in the popular conscious. In the last meaning we assign to this genre a huge art-educational mission.

* * *

The topic of the poster for the author of these words is not accidental. In the years of the civil war (1918-1922), he got to head an editorial serving the Red army. One of the important parts of this work was posters. [page 4] Participating directly in creation of a poster made this author write this essay, reporting on personal experience and some facts kept in his memory.

The work offered here is not research on revolutionary poster, pretending to be the final word and an exhaustive analysis of its formal characteristics or its complete historic development, — it’s not yet time for such a work.

But if this book serves as a source for future historians of the revolution and art, and if it underlines the role the poster played in the years of struggle, the author will be satisfied.

Moscow

May 1924

V [page 49]

Apart from others, but prominently, stands “Okna satiry” [“Windows of satire”] of the Russian Telegraph [page 50] Agency. Having established branches in the biggest provincial centers, Rosta took up residence in big store fronts, in the windows of which they displayed big sheets filled with satirical cartoons and captions, made by hand. One could not count the number of topics the Rosta “windows” addressed: it would mean to make a list of all events of the revolutionary epoch — economic, political, military, daily life, and many others. Rosta made their “Windows” as dictated by a telegraph bulletin. After getting a radio, before news hit the newspapers, Rosta artists with speed rivaling telegraph, often in the night time, prepared their “satirical” observations. These sheets were not to be mass reproduced. Their colorful look was therefore much richer than that of a poster. The drawings were accompanied by a rhyming text, a ditty, or an epigram. There were countless topic, so each “window” contained several pictures, either representing one issue, or just displayed together in one window. This was a handmade magazine, made for collective use, but unfortunately very limited, since the Rosta “windows” only served a small population of citizens. Stencils couldn’t fix this flaw, [page 51], they were later used to mass produce the “windows of satire.” Stencil method only allowed provincial towns to reproduce the drawings of big city artists, often very high in quality. Having not expanded the scope of propaganda, stencils played a significant role in art education: provincial artists, most often revolutionary youth, used them to learn from, copying achievements of their more advanced comrades. The biggest organizational achievement of “windows of satire” belongs to the artist M. Cheremnykh and the famous poet-futurist Vladimir Mayakovsky. Their exceptional energy is responsible for most of these sheets. Other than Mayakovsky and Cheremnykh, the following artists worked for Rosta: Ivan Maliutin and Lavinskii (in Moskow), Brodaty, Radakov and V. Lebedev (in Leningrad). Among the provincial artists, the most valuable original “windows of satire” were in Rostov-on-the-Don, Kharkov, and Kiev. The haste, with which this work was created, of course, was reflected in the character of the “windows.” Almost all drawings are sketches, hastily colored, always bright, often talented, mostly worked in the style of cartoon and caricature.

Translation 2: “How Many Millions of the Hungry?–10!” by Vladimir Mayakovsky

Title: How many millions are hungry? — Ten!

- This is what needs to be considered and weighed

- Two million,

So they don’t starve,

The government will help

- Cooperation will attempt

To help also

Will feed one million

- Let’s say half a million

Narkomtrud [people’s commission on labor]

Will find work for

- Half a million themselves

Will find work

- Tsentrozvak [Central Board for the Evacuation of the Population] to one million

Will be able to feed

Therefore together with the other five

- ARA feeds

It will be able to

Feed a million children

- A foreign worker helps,

He’ll be able

To give food to one million

If the help will arrive smoothly

Even the government is not able

To fee everyone

- About seven million will be provided for

- Three [million] remain hungry

- Comrade, watch after them yourself

Save 3.000.000 from their death

- Help the three!

Do you hear this plea? —

“If you don’t help – we die!”

Max Jelen is a senior History major.