By Charlie Fair

Lavr Kornilov at a military parade, c. 1917

Russia is no stranger to military coups. The army has a long history of pulling off the leash of state control and turning on its master, often at the instigation of actors within the state apparatus. When Catherine the Great overthrew her husband Peter III, she did so at the head of an angry mob of soldiers. Even today, Russia is no stranger to losing control of its own military, as just over a year ago, in a bizarre series of events, the Wagner Group attempted to march on Moscow with an ill-defined list of objectives against perceived slights and ills inflicted upon them by state and military leaders.

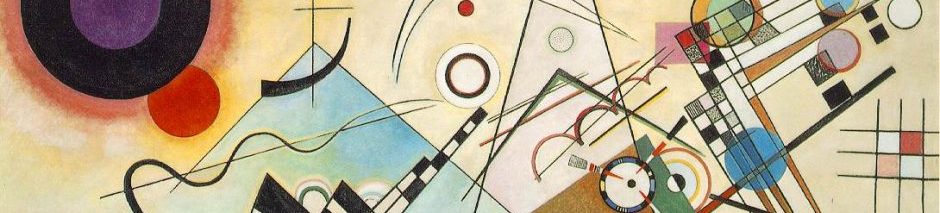

The very-much-not-dearly departed Yevgeny Prigozhin’s failed coup-de-état reignited my interest in Kornilov Affair, an arguably even more strange coup that on paper seems to be just a revolt of bitter, angry military officers, but at a deeper glance has compromising evidence on a vast swath of Russian politicians, officers, and more.

The Kornilov Affair, and Lavr Kornilov himself, have often been swept under the rug in Russian historiography – barely a footnote in the violent and chaotic chapter of Russian history between the end of the monarchy and the beginning of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Lavr Georgiyevich Kornilov was born a man of dubious ancestry – biographers and his own family have claimed possible Polish, Kalmyk, Mongolian, Russian, Cossack, Oirot, and Altai descent – and was truly a man of the worldly Russian Empire. He became a war hero during the First World War – beloved by his men for his bravery and despised by his superiors for repeatedly going on the offensive at the result of staggeringly high casualties (including getting himself and his entire division captured).[1]

Kornilov replaced Aleksei Brusilov in 1917, who although had become a national hero a year prior, had quickly worn-out his welcome for the new Revolutionary Provisional Government and the Russian public after the failed July Offensive, commonly known as the Kerensky Offensive named after then War Minister and later Minister-Chairman of the Government Aleksandr Kerensky. Kornilov was then given the unenviable task of restoring order in the Russian Army, keeping the Provisional Government secure, and somehow prosecuting the disastrous First World War to a Russian victory.

The Russian Army was already collapsing before the Kerensky Offensive shattered it, with soldiers refusing to follow orders and incidents of officers being murdered by their own men becoming regular occurrences. The Provisional Government, a body comprised of Russia’s still somewhat moderate intelligentsia, was consistently hamstrung by the regional Soviets, with whom they were in a power-sharing agreement known as ‘dual rule.’ This proved to be a political nightmare, with the fully radicalized Soviet promoting measures of ‘democratization’ in the army – namely the complete destruction of rank and physical power the officers had over their own men, causing a complete and utter breakdown of discipline in the army. Kerensky, now at the controls of the state, found himself trying to keep officers from being strung up and shot by their own men, while at the same time keeping the Soviets happy, who repeatedly called for him and his government to be overthrown.

Kerensky at the front, 1917

Kerensky’s failed offensive was a massive blow to the credibility of the Provisional Government. It caused a series of resignations, and in the streets of the capital, armed bands slaughtered one another and fought with the few loyal and intact military units to overthrow the government. As Kerensky and his ministers attempted to put out the inferno, he was discredited across the political spectrum. The left saw him as an enemy of the proletarian revolution while the right no longer believed he could keep Russia secure. This upheaval following the end of his offensive is known in historiography as the July Days, the anarchy which was ended largely by Kornilov. Soldiers loyal to him alone secured the capital and fought off the Red Guards of the Bolsheviks, who were spearheading the armed resistance against the Provisional Government. Swaths of Bolshevik leaders and strongmen were arrested, and Lenin himself fled into exile to Finland.

In preventing a Bolshevik takeover, Kornilov had only further strengthened his status in the army. He also now found himself a darling of the conservative and reactionary forces of Russia. Kerensky continued to lose face with his right-wing and center allies. The beleaguered Minister-Chairman could not contain the demands of the Petrograd Soviet, and he could not halt the ‘democratization’ of the army, which saw the state lose further control of its military. The industrialists and bankers of Petrograd communicated to Kornilov through his officers as early as April 1917 at organizing an attempt to crush the Soviets and Left-Revolutionaries.[2]

Kornilov died before the real chaos of the Civil War could begin, and also long before he could put pen to paper like many of his colleagues in the army would so in their respective postwar careers, illustrating their complex ideas on politics, nationality, economics, and society. It is therefore difficult to ascertain what he truly believed in and what he desired for Russia, as nearly all of our knowledge on Kornilov’s beliefs come to us from second-hand testimony, much of which often puts words in the general’s mouth. Kornilov supported the February Revolution and was in favor of land redistribution.[3] He also colluded with known murderer and terrorist Boris Savinkov, who possessed an even more incoherent political ideology that tended to shift on a dime (and more accurately, the current political winds and favors).[4] In 1937, General Nikolai Golovin attempted to summarize Kornilov’s beliefs in his Rossiiskaia Kontr-Revolutsiia [The Russian Counter-Revolution]:

“One thing is true, Kornilov was neither a socialist nor a reactionary. It was in vain to look for any party stamp… The main motive of General Kornilov’s entire behavior was a strong patriotism, which was aroused to the highest point of boiling in the form by the decaying army and the country, which was rapidly going into the abyss of anarchy.” (Golovin 1937, Pg. 12)

Fellow generals, subordinates, and elements of the Russian middle and upper class met with and egged on Kornilov to take some sort of action against the Provisional Government.[5] Though the July Days had been wrapped up and the Bolsheviks soundly thrashed, whispers emerged of a dubious imminent Bolshevik uprising in the capital. On August 3, Kornilov made the first move in a confusing game of chess of whose true intents and actions remain a mystery to this day. A note was issued to Kerensky and his ministers, with the following demands:

“The main of these priorities were: distribution to the entire territory of Russia in relations of the rear-exit army and the population at the jurisdiction of the military-revolutionary courts, the application of the death penalty for a number of the most serious crimes (mainly military); the restoration of the discipline power of the chiefs (officers); the establishment of the military committees in the framework of the military” (Golovin 1937, Pg. 14)

Kerensky had mixed feelings about Kornilov’s demands. According tothe historian James White, the Minister-Chairman believed they were “quite acceptable in principle, but formulated in a way and supported by such arguments that announcement of them would have led to quite the opposite results.” (White 1968, pg. 199) As Kerensky continued to reply in non-answers (finally declaring that the demands must be revised)[6], Kornilov was suddenly on the move. The day after Kornilov handed his note to Kerensky, he ordered the 3rd Cavalry Corps – who had been lurking on the Northern front as half a force to hold back the German advance, half to run back to the cities to put down any further insurrection – to the general Petrograd area. Confused, General Lukomsky asked Kornilov why, the latter giving the vague order ‘to maintain the Northern front.’ Several days later, Kornilov admitted to his chief of staff-

“My object in moving the Cavalry Corps is to have it at hand in the vicinity of Petrograd at the end of August and, if this manifestation of the Bolsheviks takes place, to deal with the traitors of Russia as they deserve to be dealt with. I intend to place General Krymov at the head of the operation. I know, if necessary, he will not hesitate to hang all the members of the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies.” (White 1968, Pg. 199)

Kerensky’s relations with Kornilov and the Army continued to deteriorate. Between August 4 and 10, Kornilov’s minions Savinkov and Filonenko revised Kornilov’s note as instructed, but instead of making it more agreeable to Kerensky and his government, escalated the demands. Now, along with having a blank cheque to use whatever measures necessary to restore order in the military, Kornilov wanted the railways under military control, the restoration of insubordination as a capital crime, re-establishing military courts, the placing of all factories producing weapons and other armaments under martial law, the establishing of a quota of goods, the dismissal of all workers who refused the ultimatum, and finally, all strikes were forbidden and made a capital crime until the war ended.[7]

Sketches of Kerensky (left) and Kornilov (right) at the Moscow Conference, Yuri Artsybushev

The last official dialogue between Kerensky and Kornilov was from August 25 – 28 at the Moscow Conference, a political assembly between the discordant factions of the Provisional Government. Kornilov had come to the conference fully prepared to rail against the Soviets and to rally the army, but Kerensky had taken him aside and forbidden him from addressing anything other than strictly military affairs, enraging Kornilov.[8]

Roughly a week after the conference, a rapid series of suspicious, late-night meetings occurred among Kornilov and Kerensky. Prince Lvov, the former head of the Provisional Government, paid a visit to Kerensky and warned him that he was “dangerously lacking in support”, and that “formidable” elements were opposed to him.[9] Lvov recommended that Kerensky reorganized the government to satisfy ‘a large element of Russian society and the people.’[10] On the night of September 5th, Kornilov met with Savinkov, who lied twice – first that Kerensky had approved his inflammatory memorandum, and second that Kerensky had approved using the 3rd Cavalry to put Petrograd under martial law. On that same night, Kornilov received visits from a suspicious amount of government figures from across the political spectrum, directly and openly talking about who they will appoint in a ‘reconstituted’ cabinet. Kerensky, despite growing increasingly wary of Kornilov, was still ironically supportive of most of his efforts, namely the restoration of order in the army.

The following night, Lvov met with Kornilov as a direct line of communication between the latter and Kerensky. Lvov claimed that Kerensky had agreed to reorganize the government along the lines of Kornilov’s measures. Kornilov additionally demanded the following: Martial law in Petrograd, all military and civil authority be transferred to the Supreme Commander (him), and most critically – all ministers, including Kerensky, must resign. This was framed as a temporary measure, in which the current Provisional Government would be suspended, letting Kornilov have a free hand in wiping out the Soviets and other Revolutionary bodies who continued to undermine the state and the army. But whether with malicious or very poorly phrased intent, Kornilov insisted that while this happened, Kerensky should come into Kornilov’s custody so that he could be “personally responsible for his safety.”[11]

Kornilov left these series of meetings fully confident that he had the backing of the entire Provisional Government. His last line, however, had made Kerensky and his remaining allies panic, now believing Kornilov was attempting a full military coup to overthrow the Provisional Government.[12] The Supreme Commander of the Russian Army sprang into action, telegramming allies and subordinates to mobilize their forces and seize major urban centers. Kornilov then turned his eyes to the capital. After receiving yet another non-answer from Kerensky as final confirmation, Kornilov issued a proclamation to his troops. He accused the Bolsheviks of being German agents, and that an imminent German-Bolshevik invasion would conquer and dismember Russia. He appealed to the army and to the people, declaring that “the life of the motherland is in your hands!”[13]

Kornilov and his officers, July 1917

As Kornilov marched on Petrograd, the Duma and the military began issuing contradictory orders, with some resigning their posts as instructed by the original plan and others remaining defiant at Kerensky’s insistence. Kornilov never explicitly called for an overthrow of the government, but Kerensky omitted words of his proclamation while spreading word, twisting it into a more aggressive, militaristic tone.[14] As Kornilov neared the capital, panic, not patriotism, seemed to grip the hearts and minds of the people. Kerensky’s public denunciations alerted the Petrograd Soviet, who were further aided when Kerensky released Bolshevik prisoners and allowed the Red Guards to re-arm themselves. By September 10, effectively outlaws, Kornilov and his subordinates realized that they had no legitimate support from the government, and now vastly outnumbered by scores of armed Bolsheviks, they were no longer able to swiftly overwhelm the Soviets with their cavalry.[15] Kornilov halted his officers, and General Krymov shot himself.

The aftermath of what was deemed the “Kornilov Affair” was swift. Kornilov and a whole swath of military officers and generals were sacked and thrown into Bykhov prison, surrounded and guarded by military men loyal to Kornilov. Kerensky’s anti-Kornilovite purge made the army go berserk, as the closely-knit officer organizations were enraged that he had been dismissed.[16] Kornilov’s removal from office and subsequent end of Kornilovite measures to restore order caused a final collapse in the discipline of the army, as now the center and right-wing forces in the military turned on Kerensky.[17]

Kornilov arrives at the Moscow Conference, August 1917

If Kornilov truly sought to end the Provisional Government, then Kerensky had saved himself from such. Yet his quashing of the Kornilovite block had not only led to the arrest of officers loyal to Kornilov, it also swept up those merely sympathetic to him, robbing the Provisional Government of its last true loyalists in the military. Meanwhile, the Bolsheviks, who had been on the ropes since the July Days, were now back in full force, with Kerensky having released scores of them and worst of all, allowed them to armthemselves. The Bolsheviks, a force that had been actively attempting to overthrowthe government, now had scores of rifles and machine guns it had no intention of handing back to the civil authorities and the commissars.

“Having entered the fight against Kornilov and ‘Kornilovshschina’, A. F. Kerensky missed the subsequent moment and deprived the country of the last chance to get out of the state of disintegration and re-establish a serious and strong revolutionary power.” (Milyukov 1921, pg. 3)

Today, well over a hundred years after the fact, it is still incredibly difficult to figure out the motives behind every strange and often botched action of the Kornilov Affair. Kornilov, though a very much autonomous agent acting with his own ill-defined goals, was also the face of a wide, semi-organized bloc of Russian officers, politicians, and economists who found the state of affairs that Kerensky had led them in to be completely unacceptable. Kerensky, a political idealist to a fault, was constantly beset by agitation from both the left and the right and sought to preserve the government’s authority and power at all costs. Despite this, there are factors in the chain of events leading up to the Kornilov Affair that do not allow the clear-cut separation into Kornilov vs. Kerensky. If the Affair was simply a mutiny of conservative and reactionary officers, why had there been such cloak-and-dagger in the nights prior, with well-to-do liberals, progressives, moderates, and others meeting with Kornilov and Kerensky? Why had Kerensky begun to entertain the idea of letting Kornilov run the Petrograd Soviet, then abruptly change his mind at the final second?

James White’s “The Kornilov Affair: A Study in Counter-Revolution”alleges that Kerensky was supportive of Kornilov marching on Petrograd initially, but soon realized that in a subsequent reformed government under the auspices of the military, he would be a powerless figurehead being used by military strongmen for legitimacy. He therefore broke with Kornilov and denounced him, and the subsequent placing outside the law made the factions within the Kornilovite bloc panic and turn on one another – officers, financiers, and all.[18]

Kerensky’s tossing-under-the-bus of Kornilov would have dire consequences for the Provisional Government. Power was handed to Nikolai Dukhonin, a competent staff officer but totally unequipped to save the Russian Army from finally falling apart. He would later be hacked to pieces following the October Revolution by a Bolshevik mob. Kerensky and his government were run out on a rail by the Bolshevik coup, and soon after, any remains of the Provisional Government evaporated. The anti-Bolshevik resistance would form largely out of the army and the same officers who Kerensky had arrested, not the intellectuals who had constituted the Revolutionary Government of 1917. Kornilov would lead this anti-Bolshevik resistance in the South of Russia for some time, before being abruptly killed in the Siege of Ekaterinodar only just at the start of the Russian Civil War. While we still do not possess the full picture of what truly occurred in that confusing, chaotic week in September, one wonders that had Kornilov successfully marched on Petrograd, that the word “Soviet” would even be in the English vocabulary.

Charlie Fair is a junior majoring in Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies. This blog post is part of his 2024 Undergraduate Summer Scholarship project on the anti-Bolshevik forces in revolutionary Russia.

WORKS CITED

Golovin, Nikolai. Rossiyskaya Kontr-Revolyutsiya. Vol. II. Biblīoteka “Ill︠i︡ustrirovannoĭ Rossīi,” 1937.

Milyukov, P. N. Istoriia Vtoro Russko Revoliutsii. T. 1. Vyp. 1-3. Sofiia: Rossisko-Bolgarskoe Knigoizd-vo, 1921.

Stone, Norman. The Eastern Front 1914 – 1917. Penguin Books, 1998.

Suvorin Boris. За родиной: героическая эпоха Добровольческой Арміи 1917-1918 гг.: Впечатления журналиста. Paris: О.Д. и ко, 1922.

White, James D. “The Kornilov Affair: A Study in Counter-Revolution.” Soviet Studies 20, no. 2 (October 1968): 187–205. https://doi.org/https://www.jstor.org/stable/150017.

[1] Norman Stone, The Eastern Front 1914 – 1917 (Penguin Books, 1998), 137.

[2] James D White, “The Kornilov Affair: A Study in Counter-Revolution,” Soviet Studies 20, no. 2 (October 1968): 187–205, https://doi.org/https://www.jstor.org/stable/150017, 187 – 188.

[3] Nikolai Golovin, Rossiyskaya Kontr-Revolyutsiya, vol. II (Biblīoteka “Ill︠i︡ustrirovannoĭ Rossīi,” 1937), 11.

[4] Suvorin Boris, За Родиной: Героическая Эпоха Добровольческой Арміи 1917-1918 Гг.: Впечатления Журналиста (Paris: О.Д. и ко, 1922), 24.

[5] Golovin, “Kontr-Revolutsiya”, 13

[6] White, “The Kornilov Affair”, 198

[7] Ibid, 198 – 199

[8] Golovin, “Kontr-Revolyutsiya”, 18 – 19

[9] White, “The Kornilov Affair”, 201

[10] Ibid, 201

[11]Ibid, 203

[12] Ibid, 204 – 205

[13] Golovin, “Kontr-Revolyutsiya”, 37

[14] Ibid, 38 – 39

[15] Ibid, 57 – 58

[16] Ibid, 52

[17] Ibid, 63

[18] White, “The Kornilov Affair”, 205