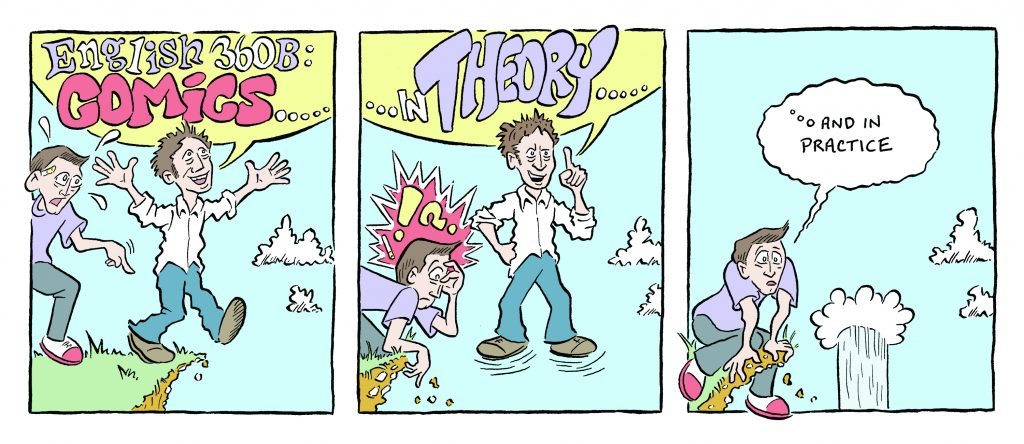

Last semester, back when things were strange in the way we call “normal,” I was thrilled to be in the course ENG 360B: Comics in Theory and In Practice, co-taught by professors Jody Bates and Patrick Murphy. I had tried making comics before but always stopped short of completing them, but this class gave me the tools I needed to return to this incredible form of art and creative writing. When I decided to start this series of professor spotlights, I knew I wanted to learn more about Dr. Murphy’s work in comics. And now, with this interview, you can learn more too! — Lauren Miles

Lauren Miles: How did you get started with making comics? Tell me about the people/institutions/etc. that supported you.

Patrick Murphy: I suppose you are asking that because I’m in the dubious habit of drawing comics for my classes? It’s not always the regular or recommended practice for those who teach courses on medieval literature and the history of the English language. But I just keep coming back to comics. I drew them at the coffee table before afternoon kindergarten. I made them in middle school. I submitted unsolicited strips to my college newspaper. There must be something in the medium that calls to me. When I first started teaching in graduate school, it wasn’t long before I was making “teaching comics” and photocopying them for class: cartoon guides to close reading, slapstick metaphors for topic sentences, that sort of thing. At one point, a mentor asked me to deliver a talk on medieval literature to a cavernous auditorium of undergraduates. I was terrified. Naturally, I went home and immediately began drawing with a felt-tip pen on printer paper. It was like a gag instinct. I brought a stack of cartoon diagrams to the overhead projector, and comics carried me through the ordeal. Now I wouldn’t lecture without them.

I must say that everyone has been so understanding and supportive. My mother praised my stick creatures. Classroom buddies tolerated my stapled, serialized stories of talking bathroom plungers. I was not thrown out of graduate school. The chair of the English department looks the other way and pretends to be distracted by something uncommon happening in the hallway when I purchase pen nibs with my professional expense account.

LM: What other creative artists have inspired the style of your work?

PM: The apocryphal story goes that as a three-year-old I asked my mother for a one-way plane ticket to California so that I could go to work for Walt Disney. “Disney’s dead,” my sister interjected. When I was older, I scissored out each daily “Calvin and Hobbes” and taped them into notebooks. The newsprint grew yellow as it aged. In high school, I became obsessed with George Herriman’s classic Krazy Kat, which is about a cat in love with a psychopathic mouse. More recently, Michel Rabagliati, Lynda Barry, and Alison Bechdel have also been very inspiring to me, in different ways.

LM: What are you reading currently?

PM: Well, I’m working on a comic about the history of the English language and the current chapter is about “correcting” grammar and rule-writing. So right now, to be perfectly honest, I’m reading a lot of rather dry articles about eighteenth-century prescriptive grammars. Fun fact! Early grammars referred to exclamation points as “shrieks” (!) and advised against using them too frequently!

LM: For potential students: how would describe your teaching style?

PM: I guess I would say I’m “informal” but “on task”? In discussion, I try to have a very calculated plan for producing moments of spontaneity.

LM: What is the no. 1 thing you want Miami Creative Writing students to take with them or have learned by the time they graduate?

PM: The last two questions got me thinking about interrobangs, which you probably already know (‽) are exclamation points and question marks mashed together. In class, the best moments seem to come when a sudden shriek of insight opens up a cacophonous chorus of new questions and everybody raises their hands at once. I miss that, these days. But the same thing can happen at home, at your desk, when you are writing a paper or pursuing a creative project. These moments feel spontaneous, but there are ways to get them to bubble up with more regularity and to amplify their pop. I hope our majors feel equipped and empowered to cultivate their own interrobangs, always.

LM: And my favorite question: what is your least favorite book that you have read and how has it influenced your creative work (or perhaps your approach to teaching)

PM: There’s a classic comic strip called Nancy by Ernie Bushmiller, which was tremendously popular in its day. When I myself pick up an anthology of Nancy strips from the 1950’s, I don’t always experience a laff riot of pure pleasure. But studying Bushmiller’s work can be very illuminating for understanding the formal features of comics and their intricate design. Mark Newgarden and Paul Karasik have written an entire (and quite thick) book dissecting a single Nancy strip, and that’s the sort of book I can really sink my teeth into.

As someone who studies medieval literature, I would also hazard that frustrating texts are often the most fascinating. Displeasure or confusion can force us to shift our perspective, to seek to understand the value other readers found in books we find totally baffling in their mysterious purpose or appeal. In my medieval literature classes, I often start things out with a totally enigmatic, bonkers text (like the Old English “Wulf and Eadwacer,” for example, or the gnomic poem known as the “Cotton Maxims”). Why would anyone slaughter a sheep to make the parchment to record such a thing? What on earth could they be thinking? Taking a question like that seriously can be a good start to a semester.