Han Kang’s Human Acts, in translation by Deborah Smith, is an exercise in memory and postmemory, a necessarily brutal rendering of trauma and its complex relationship with time and language. In this 2017 novel, which inhabits the framework of real historical occurrences, Han employs strikingly human voices (including her own) to recall the loss of a young boy’s life during the Gwangju Uprising of 1980. Each chapter steps forward in time to visit another life that struggles to understand its own living after this death. The Gwangju Uprising itself was an occasion of death, a violent ten days that saw Gwangju citizens organizing themselves against South Korean national military forces who had killed local university students protesting against the looming Chun Doo-Hwan dictatorship. The death toll is still unknown, recently placed by a BBC News report as somewhere “between one and two thousand.” These murdered bodies are where Han begins, a viscerally overwhelming motif in the novel’s first chapter, illustrating the magnitude of tragedy that Han proceeds to slice slowly into, so that the reader bares and must bear the buried bones of human cruelty with each chapter.

The opening voice of the book is that of Dong-ho, the young boy himself, a middle-schooler who joins a small volunteer force that organizes the conflict’s dead bodies for identification, all the while looking for his friend who has gone missing in the days previous. This first chapter, spilling with corpses, is written in self-address, which reads as both a difficult and intriguing choice. For example, Dong-ho’s narration begins with the statement, “‘Looks like rain,’ you mutter to yourself” (1). This word, “you,” literally haunts the rest of the novel, as every other narrator addresses it in their own chapters. While the “you” only sometimes refers to Dong-ho himself, it acts as an anchor within the text to which his ghost is tethered. Its constant presence denies the reader the privilege of forgetting.

The other voices that follow Dong-ho’s belong to, in order, Dong-ho’s missing friend, an editor for a small, struggling publishing house, a tortured prisoner, an ex-factory girl with dying ties to radical activism, Dong-ho’s mother, and Han herself, this final chapter effectively blurring the lines between fact and fiction. The childhood recollections that Han shares in this final section, explaining that the real Dong-ho had lived in the housing vacated by her family when they moved from Gwangju to Seoul and that he had been known by people in her family, amplify the dissonance between the living and the dead that she illustrates. How is it that these small, near insignificant connections between people have such an inescapable hold on our living selves? In every chapter, these faint tethers of connection can be found, like the invisible string holding the confused, non-corporeal spirit to the rotting body, and together these connections realize the delicate web between people that Han weaves.

The delicacy of these links is evident as they quietly reveal themselves in each section. The narrators’ stories are held together not only by shared, but also mirroring experiences. As an example, the editor’s chapter follows the seven days it takes for her to deliberately forget the seven slaps she received in interrogation — interrogation by an opponent to her and her publishing company’s efforts to translate and publish a play directly responding to the Gwangju Uprising for which she was present. Here, memory is at war with itself, as censorship threatens to erase the event entirely from South Korea’s national narrative, but it is clear that for the editor herself, forgetting is the closest thing to release besides death itself.

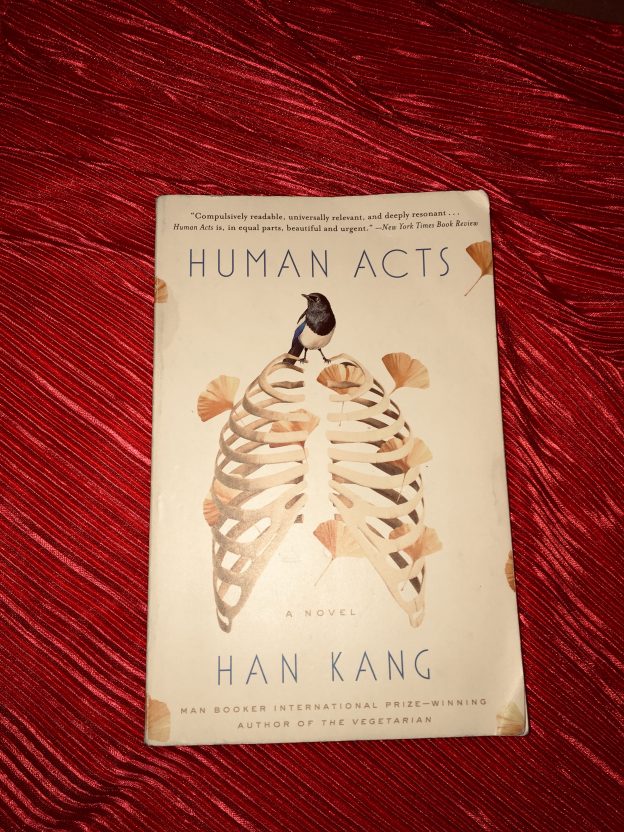

The characters’ constant struggle to access their own language to reveal and revisit the effects of their experienced trauma recalls Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee and the two books’ shared postmemory not only of the Gwangju Uprising, but of imperialist attempts to eradicate the Korean language entirely — readers of Cha will find distinct echos of her in Han’s work, despite Han originally writing in Korean, and Cha in (mostly) English. Deborah Smith’s clean and thorough translation into English shines in Human Acts, and fans of The Vegetarian, Han’s previous novel that won a Man Booker Prize for both her and Smith, will find Smith’s translation more seamless in this round. These readers might also know what to expect from another Han novel (although Human Acts is anything but predictable) — an obsession with the root of violence, disorienting changes in narrative structure as it fits itself around the movement of time, and most of all, a deeply compelling desire to find what exactly it means to be human, however terrifying that may be.

Sarah Berg is a senior from Oxford, OH. She is an English Literature major with minors in Asian/Asian American Studies, Creative Writing, and Art History. Her research interests lie in poetics, Korean literature, and translation.