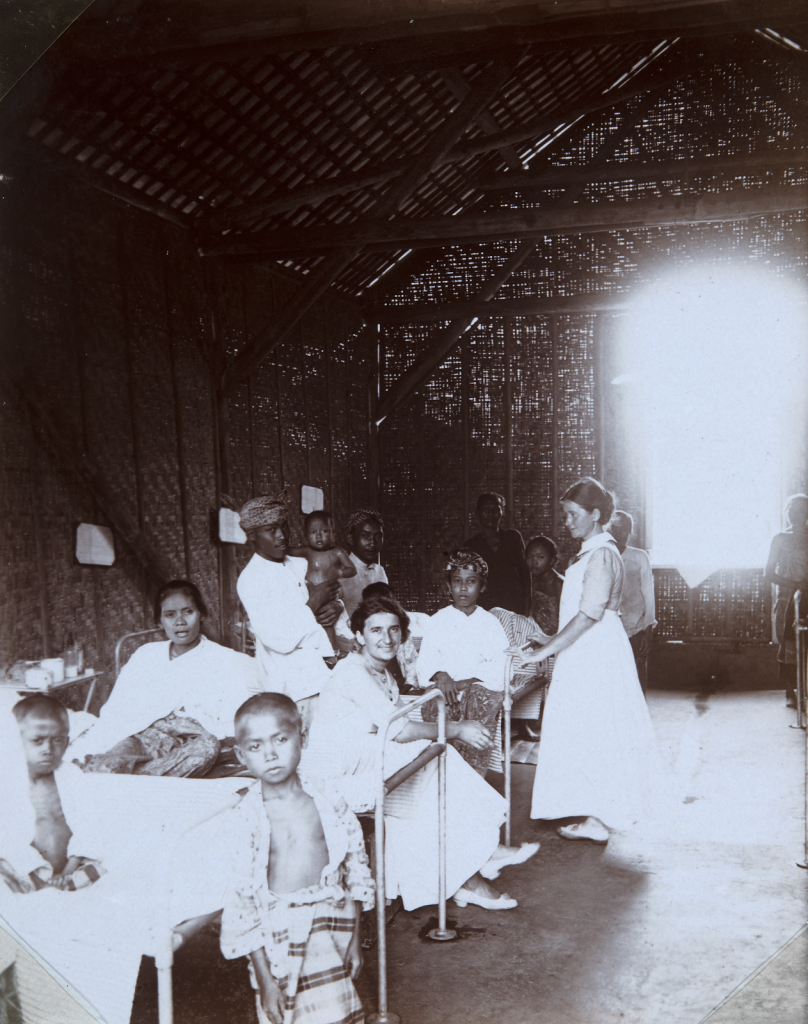

Children’s ward with nurses and visitors in a nursing institute in Java

By Gretchen Blackwell

Note: Essay 3 in a series, all from Dr. Amanda McVety’s Spring 2019 class on Medicine and Disease in Modern Society

Beginning in 1894 and lasting until around 1950, a pandemic of the plague began to spread, wreaking havoc on much of the developing world. This pandemic was the third outbreak of its kind, harkening back to the days of the Plague of Justinian that occured around 541-542 AD and the Black Death that desolated much of the world between 1347 and 1500 AD, both of which killed millions and reshaped the political and social spheres of the world. When the plague spread in the early 1900s, clinicians, politicians, and researches were no more prepared for its destruction than those of outbreaks before germ theory was developed. Despite the various methods of prevention, cures, and treatment employed by public health officials, the outbreak in colonized countries, where the cities were overcrowded and unsanitary, worsened drastically. The actions of officials were met with much protest and resistance from citizens, as many did not trust any Western medical interventions. Though the third outbreak of plague ravaged the majority of the world, the rich and powerful West was unscathed. Consequently, the memory of this outbreak faded in the minds of the West; yet, its devastation marked the beginning of a clear inequality in health care in those countries affected by the plague and the developed world.

The plague, a contagion caused by Yersinia pestis, is transmitted by rodents and their fleas. There are three types of plague- bubonic, septicemic, and pneumonic, the most deadly. A person can catch the plague from being bitten by an infected flea, handling carcases of rodents with the disease or, in the case of pneumonic plague, from Y. pestis particles transmitted person to person. The plague kills by reproducing its bacteria rapidly and overloading the immune system until the organs fail. The symptoms occur around six days after infection and have various effects depending on the type of plague.[1] In bubonic plague infections, the patient’s lymph nodes swell, and the patient experiences fever, aches, and chills. When infected with septicemic plague, the patient develops fever, chills, shock, and bleeding under the skin that causes the blackening of skin tissue, a characteristic that is typical of this type of the disease. When either bubonic or septicemic plague is left untreated, it can develop into pneumonic plague which causes pneumonia.[2] There is no vaccine available for the plague; however, if it is treated with antibiotics, the patient has an increased rate of survival.[3] If the plague is left untreated, the patient has a 50 percent survival rate.[4]

During the third outbreak of plague, no cure or treatment was known, and there was a lack of understanding of the exact mode of transmission. The theory that rats spread the plague developed during this time; however, it was accepted by many that human to human transmissions occurred in every case of the plague, some even attributed miasmic theory to the outbreak.[5] Ultimately, public health officials resorted to the methods used in past pandemics. These methods included quarantining and the burning homes and belongings of victims, forcing them to relocate, in order to stop human to human transmission, what they assumed was causing infection. Additionally, officials would roundup and poison rats in order to control the spread of disease. Further, vaccination, a method that has now been proven very dangerous, was compulsory for citizens of Senegal.[6] None of these efforts did much, however, to fight the pandemic.

Many actions taken by health officials during the third plague pandemic were met with resistance in colonized nations, as the officials were ignorant of or apathetic towards the cultural and religious traditions of the colonized people. For instance, in India, citizens reacted with violent protests when forced to conform to Western medical practices, leading “to the death of four Britons, and helped accelerate the growth of Indian nationalism.”[7] Further, in Bombay in 1936, it was reported that after objections from citizens, officials would stop the trapping of rats because of the religious beliefs.[8] The title of an article from the Sunday Times of London read “Plague Preferred”, showing a clear inconsideration of the values of the society in which Britain was occupying. In the West, it was thought that only those who were ignorant caught the plague. In fact, when there was an outbreak in Scotland, officials were embarrassed by its presence.[9] It was generally accepted that backwardness and uncleanliness would cause the plague. A medical professional in the American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health in 1934 claimed that it was “ignorance and fear” that worsened the fatality of disease.[10] In India, this became “an excuse for letting the plague epidemic… burn out”.[11] Officials decided to stop intervention and let the disease run its course, resulting in 10 million deaths in the country.

By the end of the outbreak around 1950, nearly 15 million were dead, primarily in the port cities of India, China, and other Asian countries. There were many deaths in Africa, South America, and Australia as well, but, comparatively, Europe and North America experienced very few casualties. The breeding ground for plague epidemics is overcrowded and unsanitary spaces, a description of many seaports in the developing world during the early 1900s. The threat of death by the plague struck so much panic in citizens of India that two men from Calcutta were sentenced to death for the murder of a man by using “bacilli serum” containing plague microbe.[12] In comparison, the West had a developed public health system that enforced sanitary codes and prevention efforts. The New York Sanitary Code from 1940 lists the rules and regulations to be followed in the case of plague, including notifying authorities, isolating the patient and the patient’s family, and quarantining the patient’s home.[13] Ultimately, these measures led to the disparate effects of the plague pandemic. In an article from The Science News-Letter from 1938, “the horrors of the plague of the Orient” are described as being far off and distant from the minds of Americans.[14] Further, an article from The Sunday Times discusses the public health efforts to prevent infection and how the threat of plague has been “happily” reduced in Britain because of them.[15] While the majority of the world was being ravaged by the plague, the disease was barely on the radar of Westerners.

The disparities in public health interventions that existed during the time of the third plague pandemic led to the death of millions by, as evident by the low mortality in Western countries, a preventable disease. While North America and Europe were barely touched by the disease as a result of the regulations and precautions set in place by their bureaucracies, poor and often colonized countries such as India and China experienced an unbridled pandemic that struck fear into the populations and left the countries with political and social turmoil. This sharp contrast between formally colonized countries and the Western world is still evident today. According to the World Health Organization, as of 2017 “nearly 9 million children under the age of five die every year” and “around 70% of these early child deaths are due to conditions that could be prevented or treated”.[16] Most of these deaths are concentrated in developing countries, the same regions ravaged by the plague around 100 years ago.

Gretchen Blackwell is a freshman from Huron, Ohio planning on majoring in history and political science with a minor in computer science.

Works Cited

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “CDC Plague | Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About Plague.”

(Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/plague/faq.asp.

Echenberg, Myron. “Pestis Redux: The Initial Years of the Third Bubonic Plague Pandemic, 1894-1901.” Journal of

World History13, no. 2 (2002a): 429-49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20078978, 435.

Echenberg, Myron J. Black Death, White Medicine: Bubonic Plague and the Politics of Health in Colonial Senegal,

1914-1945. (Oxford: James Currey, 2002b), 103.

Larkey, Sanford Vincent. “Public Health in Tudor England.” American Journal of Public Health 24 (November 1934):

1099–1102. doi:10.2105/AJPH.24.11.1099, 1102.

“Murder by Germs.” (Sunday Times 1935), p. 21. The Sunday Times Digital Archive,

http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/9M3dZ9. Accessed 4 Mar. 2019.

Our Agricultural Correspondent. “Plague Peril from Rats.” (Sunday Times 1937), p. 31. The Sunday Times Digital

Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/9M3Aq2.

Our Own Correspondent. “Indian City Not to Trap Rats.” (Sunday Times, 1936), p. 24. The Sunday Times Digital

Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/9Lzbq6.

“Provisions of the Sanitary Code of the City of New York and Regulations Relative to Reportable Diseases and

Conditions and Control of Communicable Diseases”(Department of Health, 1940).

Stafford, Jane. “Death Rides a Rat.” (Science News Letter, 1938), 134–35. doi:10.2307/3914747.

Unknown author “Children’s ward with nurses and visitors in a nursing institute in Java”[digital

image]. https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/285241

U.S. National Library of Medicine. “Plague.” (MedlinePlus, 2018). https://medlineplus.gov/plague.html.

World Health Organization. “Child Mortality.” (World Health Organization, 2011).

[1] Echenberg, Myron. “Pestis Redux: The Initial Years of the Third Bubonic Plague Pandemic, 1894-1901.” Journal of World History13, no. 2 (2002a): 429-49. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20078978, 435.

[2] U.S. National Library of Medicine. “Plague.” (MedlinePlus, 2018). https://medlineplus.gov/plague.html.

[3] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “CDC Plague | Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) About Plague.” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018). https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/plague/faq.asp.

[4] Echenberg 2002a, 435.

[5] Echenberg 2002a, 437.

[6] Myron J., Echenberg. Black Death, White Medicine: Bubonic Plague and the Politics of Health in Colonial Senegal, 1914-1945. (Oxford: James Currey, 2002b), 103.

[7] Echenberg 2002a, 443.

[8] Our Own Correspondent. “Indian City Not to Trap Rats.” (Sunday Times, 1936), p. 24. The Sunday Times Digital Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/9Lzbq6.

[9] Echenberg 2002a, 448.

[10] Sanford Vincent, Larkey. “Public Health in Tudor England.” American Journal of Public Health 24 (November 1934): 1099–1102. doi:10.2105/AJPH.24.11.1099, 1102.

[11] Echenberg 2002a, 443.

[12] “Murder by Germs.” (Sunday Times 1935), p. 21. The Sunday Times Digital Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/9M3dZ9. Accessed 4 Mar. 2019.

[13] “Provisions of the Sanitary Code of the City of New York and Regulations Relative to Reportable Diseases and Conditions and Control of Communicable Diseases”(Department of Health, 1940).

[14] Jane Stafford. “Death Rides a Rat.” (Science News Letter, 1938), 134–35. doi:10.2307/3914747.

[15] Our Agricultural Correspondent. “Plague Peril from Rats.” (Sunday Times 1937), p. 31. The Sunday Times Digital Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/9M3Aq2.

[16] World Health Organization. “Child Mortality.” (World Health Organization, 2011). https://www.who.int/pmnch/media/press_materials/fs/fs_mdg4_childmortality/en/.