by Hayden Uribes

When most of the residents of Storm Lake think of refugees, they no doubt think of the Hmong and Tai Dam who fled Southeast Asia following the Vietnam war. What they’re less likely to think of are Franco-Belgian refugees following WWI, Armenians, and victims of mid-century fascism. Yet those are all refugee groups whose fates have been tied to the citizens of Storm Lake. Today, the Hmong and Tai Dam of Storm Lake are a vital part of the town’s community, workforce, and business superstructure, and on some level it seems that the acceptance of these refugees may stem from a century-long tradition of support for refugee populations.

In 1914 German troops to marched through the sovereign state of Belgium, allowing the German Empire to invade its long time enemy, France, by bypassing its militarized border, leading to a series of atrocities commonly reffered to as the “Rape of Belgum.” This officially resulted in the death of over 5,520 people, with another 6,000 or so having been killed in unofficial mass shootings by lower level German Officers and over 120,000 Belgiuns being essentially enslaved in German factories. To the south, the German Empire’s allies, the Ottoman Empire, began a campaign of nationalist extermination against an ethnic and religious minority scattered throughout their empire known as Armenians. Numbers are hard to come by, as the Ottoman government is thought to have fudged the numbers, but commonly accepted numbers exceed a million casualties, and over 600,000 Armenians reduced to refugees.

While all of this was happening in the Old World, the citizens of the New World watched on with a combination of fear, disdain, and sympathy. While few refugees had ended up within the United States, a great many languished in refugee camps across Western Europe and the regions that make up modern day Turkey and Armenia. Fortunately, organizations like the Red Cross acted to provide these refugees with food, clothing, and other necessities to survive until the establishment of general peace in Eurasia, and the people of Storm Lake seem to have been happy to help.

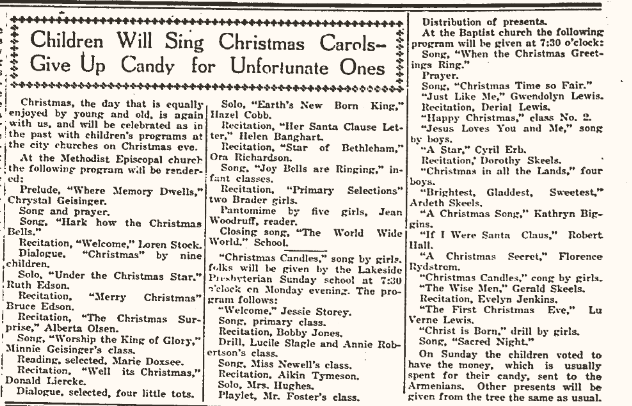

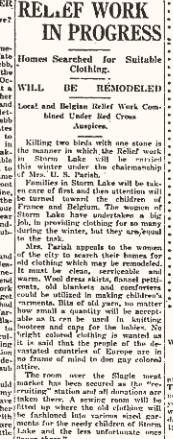

We know Storm Lakers were amicable to helping these refugees mostly because of newspaper articles covering fundraisers. For instance, in a 1917 article in the Storm Lake Pilot Tribune, a local Red Cross chapter led by “Mrs. Parish” requested donations of clothing, primarily meant for French and Belgium refugee children. In another Tribune article, the Methodist Episcopal Church is recorded as having donated funds to refugees from the Armenian genocide, and only about a year after it was created. Even decades later in the prelude to the Second World War, when Japanese forces were invading large chunks of China and committing war crimes on a daily basis, there are articles in the Storm Lake Register calling for donations to support refugees of the conflict.

As these articles reveal, of course, it wasn’t all rainbows and butterflies in Storm Lake. There was some level of nativism. In the first article, for instance, the author claims that donations would be given to locals before foreign refugees. Regardless, in both cases there’s compassion shown to outsiders, people whom the citizens of Storm Lake had never met, and in most cases never would meet. That compassion seems to have survived to the present day.

On some level, there’s a tendency for historians discussing Storm Lake to begin its history of support for refugees in the eighties, but this aspect has been present for over a century, and is arguably a part of the town’s cultural tradition.