by Piper Nicely

I am a proud resident of Toledo, Ohio: the Glass City; home of Tony Packo’s, Libbey Glass, Jeep, and Corporal Maxwell Klinger from M*A*S*H. But if you look behind the historical buildings, quirky arts district, and beautiful waterfront, you can see that Toledo houses its own troubles, specifically with our water.

Downtown Toledo is located along the shores of Lake Erie, a lake that feeds into 31 different water treatment plants on Ohio’s North Coast. My family, like the majority of those living in Toledo, gets our water supply from this lake. But now, even eight years later, I still remember waking up to a note left on the faucet by my father, the words capitalized and underlined, warning me not to use the water.

On August 2nd, 2014, a highly toxic algae bloom took over Lake Erie, rendering its water unusable for over half a million people relying on it as their only source. Ohio declared a state of emergency, and within hours bottled water sold out in stores. The news ran stories showing the lime-green water of the lake, and the people of Toledo watched in shock as we were left without water for what seemed like an eternity.

Luckily, the order not to drink (or come into contact with) our water came to an end after three days, but the paranoia and public interest it caused would last for years.

Even though I was only 11-years-old at the time, the algae bloom has stuck with me. It is a topic that still horrifies and fascinates me after seeing what damage it can cause.

Now, in our class some time back, we read Art Cullen’s Storm Lake. In it, Cullen discusses algae blooms, even comparing the issue to the water crisis in Toledo. This immediately caught my interest, of course.

As it turns out, Lake Erie and Storm Lake have something in common when it comes to these polluting events: agricultural runoff.

Agricultural runoff is when water from farm fields enters bodies of water due to irrigation, erosion, rain, or snow. As the runoff flows, it can pick up natural and synthetic pollutants, depositing them into waterways and causing “overfeeding.” This takes place when nutrients like phosphorus, nitrogen, and carbon from fertilizers are brought into the water, creating a perfect environment for these harmful algae blooms.

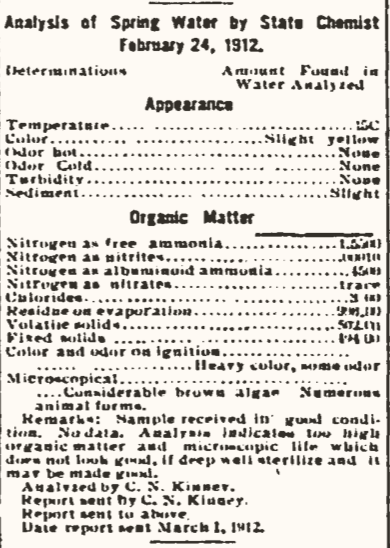

We work with historical newspapers in this class, so I began digging into some of the archives, searching for any information I could find on algae blooms in Storm Lake to see how long this has been a problem. In my research, I found troubles with water pollution and algae spanning back to 1912. Seeing over a hundred years of environmental concern was absolutely mind boggling to me, and a lot of the information I found was alarmingly similar to what we hear today.

An article from a 1912 edition of the Storm Lake Pilot Tribune gives a sanitary analysis on the water of Storm Lake. The conclusion was less than good. State Chemist, C.N. Kinney, found “high organic content” in the water and stated that it is “alive with animal organisms as well as considerable algae.”

In a 1933 edition of the Storm Lake Register, there is an article devoted to the state conservation board meeting with citizens to discuss algae in Storm Lake, its causes, and its effects. Chief speaker of the evening, William Woodcock, a member of the board, brought up a few causes of the algae growing in Storm Lake. The first was sewage disposal, something that Toledo is also guilty of, where the city was emptying its sewage into the lake. This causes another unwanted spike of nutrients for the algae in the water, allowing it to grow out of control.

The second he mentioned was agricultural runoff, something to be expected with rural communities. The article reports that Woodcock “declared that washings from barnyards and soil erosion contribute to the pollution of the lake but that nature can handle that much contamination were it not for the sewage effluent which, he says, is ‘the straw that broke the camel’s back.’”

But now nearly a century later, the camel’s back is far more than broken. It may even be beyond repair.

This has been a problem happening for so long, and yet it only continues to worsen with the onset of modern agriculture. Industrial farms and mass agriculture are exacerbating this problem more than ever. The runoff from fertilizer used to produce large crop harvests, or the waste from mass cattle, pig, or poultry farms, is far more than our waterways can handle. We see one crisis happening after another, from algae blooms making our water toxic and undrinkable to the onset of invasive species that harm the local ecosystem even more. Both Lake Erie and Storm Lake have had to deal with an increased amount of zebra mussels, a creature that disrupts our local ecosystems and harms native species.

In the grand scheme of things, there is no simple fix. Solutions like dredging and planting cover crops are expensive and stand little chance against decades of pollution. For now, though, we can only take small steps: planting the cover crops we can afford, looking into the treatment of our waste and the chemicals in the fertilizers we use, and bringing awareness of the situation to communities struggling with algae blooms and other damaging effects of water pollution.

Cullen’s recent editorial, “The River is Dead,” has a haunting message. But he’s right. It is hard to look at the world around us and see any positives coming from our current environmental situation. Whether it be growing up in a city where, at any moment, your water supply could become poisonous, or watching the slow decline of your local lake due to pollution, we all feel the effects.

And this is not a new problem. Storm Lake has been dealing with algae blooms for over a century. If it really were a problem people wanted to solve in 1912, then it wouldn’t be a problem we need to solve today. What will future generations say of ours?

Storm Lake and Lake Erie are central to our local community cultures. Both Toledoans and Storm Lakers have seen firsthand the devastating effects pollution and algae blooms can have on our waterways. It is a problem spanning centuries with no simple solutions or quick fixes.

Now is the time to look for bold long-term solutions, to look for ways to help our waterways so that, a century from now, those looking back on our newspapers will no longer see our problems reflected in their world.

Piper Nicely is a freshman journalism and creative writing major from Toledo, Ohio, with interests in cultural studies, politics, and environmentalism. Outside of class, she is involved in Miami’s League of Geeks as a member of the Role Playing Guild and enjoys reading, writing, and spending time with friends and family.