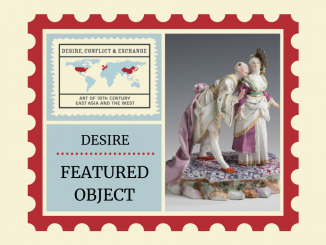

An expansion of trade and intercultural relations between East Asia and the West developed after the Opium Wars. These fueled an intense interest in the different artistic styles and technologies of these new foreign “Others”. Many Westerners saw East Asia as a place of romantic exoticism, while those in the East saw the West as a source of new and interesting technologies.

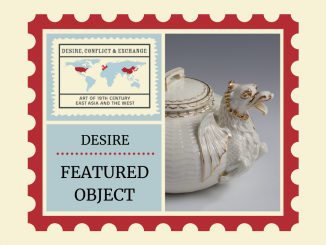

Western countries were first exposed to East Asian art in the 16th century through trade in porcelain, tea and silk. Over the next 300 years, export goods, which were limited to designated ports of Canton, China and Nagasaki, Japan, evolved for a global capitalist market and were crafted to meet Western aesthetic demands for Eastern styles. Often highly ornate and gaudy, these goods reflected orientalist fantasies of the East rather than authentic images. Western artists and writers imitated and appropriated East Asian styles. Paintings, sculptures, staged photographs, and travel books captured the idealized “otherness” of a misinformed Western audience.

Meanwhile, artists in East Asian countries were less interested in Western subject matter. They selectively adopted Western stylistic techniques like shading, horizon lines and perspectival construction of space. Pre-existing Chinese portraiture traditions were enhanced at this time through the introduction of photography, particularly in the depiction of faces. East Asian printmakers, painters and photographers combined local and Western styles to create a new, eclectic East Asian aesthetic.