Journeys into the Past: New Tevye Tales

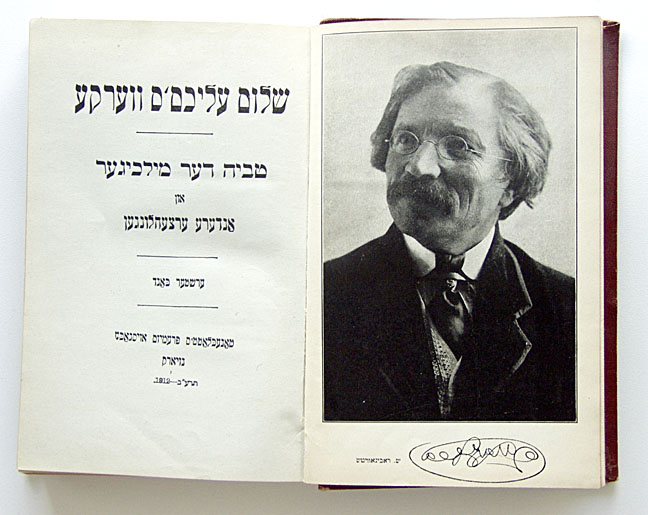

Sholem Aleichem’s popular stories of Tevye the Dairyman made the author famous within and putside the Russian Empire. Published between 1895 and 1916, the stories are mostly known today as the basis for the Broadway musical Fiddler on the Roof.

Here three students from HST 374–Addison Caruso, Tessa Ralinwosky, and Emily Erdmann–“find” lost stories of this beloved character and his daughters.

- “The Sabbath”

Found by Addison Caruso

Shabbat Shalom, Reb Shalom Aleichem. It may not be the Shabbos when you are reading it, but it is the Shabbos at my house and I have had an interesting experience that I think you might enjoy. Now, not too many peculiar things happen in the life of Reb Tevye, but this one is as I received a guest and learned a little more about the city life. Maybe you can write me back and tell me if it’s true Reb Aleichem as I’m sure you know your fair share of city dwellers. It also started this Friday night as we were getting ready for the Shabbos. I had just finished getting ready for the meal as the sun was setting that night, as you know Reb Tevye is always ready for the Sabbath and not a minute late, as it says in our Torah, “thou shalt honor the Sabbath and keep it holy” and Reb Tevye isn’t one to go against the will of God.

As I am getting ready and my wife Golde is putting the last preparations on the beautiful meal she prepared, I hear a knock at the door. “Who could be knocking at this time” I thought, as it is written in our Talmud: those who disturb a man’s peace before Shabbat are destined to get as cold of a welcome as our ancestors did in Canaan. This apparently did not trouble my Golde though as she called over to me, “Answer the door Tevye!” Oy, is it my lot in life to live with this, I love my Golde, but isn’t this what I have children for? As I open the door though, I was surprised to see a man in a suit. He looked like a big macher, with a gold pocket watch, nice suit, no beard, and fairly plump as well. “This must be a rich man” I thought. Tevye is not one to be rude to someone though, and I answered the door with a pleasant hello and asked him his business. “Hello” he said, “my name is Meir Bronstein, I am travelling from Kiev on important business, but due to the Sabbath I feel I must stop for the evening, would I be able to join you on this Shabbos meal, you will be compensated.” “Ah yes, as the Migillah says: to travel on the Sabbath is like riding a horse backwards, it works but it’s not quite the same.” “Right, I will not need lodging for the night but as I mentioned earlier could I join you for a meal tonight.” How could I turn this man away, we were once strangers in the land of Egypt, so I invited him in and quickly tied up his horse outside to not miss the Sabbath. I must mention this horse though, you have heard about my house, but this horse, its coat shone like the Tabernacle and it was so large as well. “This is definitely one big macher” I thought.

“Golde!” “Yes” she called. “We are having a guest for dinner.” “What!? A guest? No warning, no nothing! You invite a man off the street for food, we are not a charity house Tevye, we barely have enough as it is.” “Ahhhh” I said, “but he seems to have more than he needs, fix a nice meal for him, and maybe he’ll take care of Tevye and his Golde.” “Oh, alright” she lamented. I often wonder how Adam dealt when he first saw Eve, I’m sure at first he was smitten by her beauty, but then I wonder how long it took for him to try to get some personal space away from her.

As the Shabbos started, my wife lit the candles, beautiful ones passed down from her grandmother Rachel, we said the prayers and began to eat. “So what are you doing in our little village I asked?” “I have business in a few towns over.” “What kind of business?” “In Kiev I am a manager at a big factory there specializing in textiles, we have a potential client I am meeting with tomorrow morning, I thought I could make it to the town today, but alas due to various circumstances I had to depart from Kiev late.” “Ah, as the Talmud says, it’s not about the journey but about the destination.” “Tevye” my wife said, “stop with your storytelling, can’t we just have a Shabbos meal without your constant sayings?” “Alright Golde, I’ll stop, I’ll stop.”

The meal proceeded in silence for a little while as I enjoyed the delicious Challah, gefilte fish, chicken, and soup my wife had prepared. I would like to say to you Reb Aleichem, if you ever find yourself in need of a good Shabbos meal, my wife Golde makes a delicious one. My daughters help out and of course while not exactly rich, I always manage to provide a nice amount of food for the holiest day of the week. This did not escape our guest either as he commented several times on the meal. Anyway…I am sorry to ramble Reb Aleichem, as I know you have more important things than read about the deliciousness of my wife’s cooking. I will proceed to my story.

As we were enjoying our meal I heard a banging on the door. “Who could that be at this time? On the Shabbos?” my wife Golde said. As I went over to the door to check, I peered through and saw a group of people standing outside. As the man stumbled outside I opened the door. Though I had a few glasses of wine, I was still in a state of mind to conduct business, these men outside on the other hand were almost falling over. As they say in our Megillah, “if man drinks enough he may turn from a donkey to an ass.” “Hello may I help you?” “Ahhhh Reb Tevye, we heardddd you tellllll a good storyyyy spin ussss a tale!” “I am sorry but it is the Shabbos, I must refuse and go back inside, plus I have guests I must entertain.” As I turned to go back into my house I felt something sharp poke and as I turned around I saw one of the men holding a very sharp pitchfork. Slurring his words rather heavily he said, “This wasnnnnn’t a requessssst Reb Tebye.” As I began to panic, I am not good on the spot with stories, Meir walked up to the door. Pulling out a handful of rubles he said, “Leave this man and be on your way.” Ahh money, the best motivator, if only I had a little more.

As we began to walk back Meir turned to me and asked, “Why do those men bother you like this?” “Ehhh it’s just how it is, why should I question what God does.” “Yes, but is this something common here?” “What, our Russian neighbors paying us unwanted visits, the horse does not want a horsefly to pay him a visit, yet he is powerless to stop it. I am surprised you are not aware of this.” “Well in Kiev things are a little different, while I am not exactly best friends with the Russians, some of my good friends and business associates are them and I often attend cocktail parties.”[1] “With the Russians?” “With the Russians. In Kiev this is not so uncommon amongst the upper classes.” Jews mingling with Russians?? In our little village this is almost unheard of, we stay amongst ourselves and they stay amongst themselves. This is just how it is. As our great Rabbi Hillel says, “The best kind of cake is a layered cake, not a marble.”

My wife Golde seemed surprised by this as well as well as my kids. “I have unfortunately heard about the things that go on in the countryside, it’s horrible that you must go through that. I’m ashamed to say I thought they may be a little exaggerated,” Meir said. “What can a man do, it’s the lords way.” “You always talk of this lord, but why don’t you do something?” Meir retorted. “What can I do, confront them? Talk to them, you say that there are options to deal with this but unfortunately here it’s life. I don’t know if it’s humiliation, or why they do it, but why does the rooster crow every morning, it’s what they do, why ask questions.” As we sat down and continued our meal, Meir continued to talk this subject of what they call “pogroms” in the city. “I believe it is an environmental factor, mainly motivated by a social hierarchy and humiliation as they feel powerless so you are the people that they take it out on.”[2] “They feel powerless???” I almost fell out of my chair laughing. “Why don’t they try a day in the life of Tevye the dairyman, then we’ll see how powerless they feel.” “But you must look at it in their perspective Tevye.” “Why don’t they see it in my perspective then Meir.” “Understanding is the first sign of forgiveness and reconciliation Reb Tevye, maybe one day this town will be like Kiev, where you will be able to live side by side with them, and maybe even be friends.” “Wishful thinking, but hey we’ve been waiting for the Messiah for 2000 years so what’s hoping for one more miracle going to do.”

It was then that Golde brought out the dessert. I cannot tell you how happy the sight of blintzes makes me. As the Talmud says, “Dessert is stressed spelled backwards” this means that it is important to eat, and I am often stressed so a little dessert helps that good ol Tevye. As we were eating this delicious dessert I asked Meir, “Is this the kind of Shabbos food you have in Kiev?” “I must tell you something Tevye, I often find it hard to find a good Sabbath meal in Kiev, there are not many who still keep the Sabbath on a regular basis.” “Do not keep the Sabbath.” “Yes, I have occasionally missed it for meetings and parties I must admit. It is mainly the young people who do this, this secularization. It is unfortunate, I think of my mother and how she would be rolling over in her grave thinking of these kids. She moved to the city from a little village quite like this, and I am thankful for it, but as much as I’ve tried to keep my Judaism alive, it can be hard, and it’s hard to see younger generations losing their focus on Judaism. My son, for example, he does not cover his head when he goes out and I’ve even seen him sneak pork into our house.”[3]

“That’s awful!” My wife Golde said before turning to our five daughters, Tzeitel was married earlier as you remember, “If I see any treif in this house you will not hear the end of it from me or your father!” “Yes Mama!” they all said in unison. What good daughters I have, but who is surprised that Tevye has good daughters. As I was thinking of my daughters Meir turned to me and said, “Well Tevye, I believe I must be off, I would like to thank you for this good meal, it was delicious.” “It was a pleasure, King Solomon once said, a nice meal with a stranger is one of life’s small luxiries.” “Tevye” Meir said laughing heartily, “I do not know where you learned all of these sayings but it has certainly made this Shabbos that much better. Please take these rubles as a token of appreciation and I hope things keep going well with you.” As he handed over the rubles and left we saw him walk out the door.

As I held the stack of rubles in my hand my wife Golde rushed over, “Great!” she said “Now we can get another cart, you’re last one is nearly broke!” Leave it to your wife to take all the fun out of getting money. As I watched him ride away in the dark into the forest I began to think about the differences of our lives. Yes, as surprising as it might be to you Reb Aleichem, Reb Tevye does think about these things sometimes. Things are changing in the cities, and I wonder how this change will affect our little village. I often wonder how different my life would be if I was born in Kiev. While still a Jew, obviously there were successful Jews there, and friendly Russians. Maybe I would’ve been a banker, Reb Tevye the banker, the most important Jew of Kiev they would call me. I would ride around and I’d be the big macher. This is wishful thinking though, if this is my lot in life, God will deliver it. I’m sure you are getting tired of reading this letter though Reb Aleichem, like Meir you yourself are an important man so I will not take up much more of your time with Reb Tevye’s stories, but send my regards to everyone and I wish you a happy and peaceful Shabbos.

2. “Teibl”

Found by Tessa Ralinowsky

As I walked out of the house to milk the cows in the morning, the last morning I should own them, I found my sweet Teibl behind the barn sitting under a big tree. I had often found her here as a child. It reminded me of happier days, when the family had not yet been pulled apart. She sat curled up like a little bird that had fallen out of the nest. As I neared her, I noticed her distress.

“Ah, Teible! The tears of my child reach God! What brings these tears?”

“Papa, forgive me!” sobbed Teible.

“Child, lighten your heart. Tell me what ails you.”

“Conviction, father. This has always been our home, and now we are told no longer can we live here.”

My heart sank, losing my dairy farm would be a swift blow below the belt from those whom I called friends. Oi, beware of friends, enemies do not deceit.

“Sweet Teibl, do not stress. This would not happen if it was not part of our fate.” I said calmly.

“But papa,” she pleaded, “Your fate is not the same as mine. I feel as though I see my future darkening as we speak.”

“You cannot know the future until it is the present. Such is the way of life.”

“Father, I need to ask something of you. It is of the utmost importance.”

“Ask away my child.”

“Papa, I fear that while we cannot stay here, we cannot stay anywhere else near here. Haven’t you heard what’s going on around us? They are killing us Jews. We are not safe here. I have a plan to help us, but I need money to make it happen. It must happen now if we are to leave.”

“Tell me of this plan you thought up little Teibl.”

“My friend from the market, Gluke, gave me this pamphlet. It talks of a land where we could freely practice, the United States of America. It is only a matter of getting our papers all together, so we can travel there and live without fear.”

“Men fear the knife more than God himself! Teibl, what makes you want to leave our homeland? We will find peace somewhere.”

“Some from Gluke’s family have already moved. She has told me that their trip was long and difficult. But that they have made a life for themselves there, and no longer fear the pogroms, or being asked to leave their new home. I dream of a life where I can practice as I please, and not fear because of it. A land of religious freedom is what we need desperately, and if I am bold enough we can live like Gluke’s family too.”

I sat in silence for a moment. After all I had accepted with my elder daughters, I could hardly believe my ears.

“This is the land of our family, are you willing to give that up?” I asked.

“The land of my family is not here, I no longer feel tied to the land that we are not wanted on. It has been said before, ‘get thee gone thence, you must leave your native land.’ ”

She looked stubborn. She sat now with her arms folded in front of her, until she brought out the literature she had mentioned. It was titled “What Every Emigrant Should Know” and it was written in English and Yiddish. I read through it, feeling farther away from my daughter than I ever had before. I knew that my young Teibl would have no problem getting into the United States, but oh, health comes before making a living! I knew that my health would not hold out long enough to make the journey.

“You see papa, we meet all the requirements. We are lucky that you have taught us to read, this will help us get in. And Gluke has offered to help us further, not only will she and her parents travel with us, for they know the way, but she has offered to make arrangement with her family already there to make sure that we get in. She has a cousin there, and he is looking for a wife. We can be guaranteed entry if I marry him.”

This hurt my heart than more than all my previous daughters had. While they may not have conformed to my traditional wishes, they at least had married for love and happiness. This I could stand behind. But a loveless marriage? She hadn’t even met the man before! I felt my temper rising.

“My daughter, I cannot allow for this! There is so much uncertainty in your plan. If you stay with us at least you will be guaranteed happiness with your family.”

“Papa, you have taught me to love my family, and all that family stands for. But I cannot be guaranteed happiness if I stay in a land so hostile to us.”

“I have talked to your sisters. We will not stay in a land like this, we will go to our true home, in Israel. Here we will be safe, all we must do is stay together. Even your sister Chava will join us.” I explained the plan I had decided, how the whole family could move together and start over.

Teibl looked surprised at my last comment, and raised her eyebrows.

“This is where I see a fork in the road for our family. What opportunity lies in Israel for us? I fear about finding work there, and being able to support the family. The United States is a changing land, and full of work and opportunity. The pamphlet talks of Jewish organizations that will help us find work. I believe there is the best place for us to resettle.”

“I have already lost one daughter, I cannot lose another.” I pleaded with her.

I could tell this displeased Teibl. She picked herself up and ran inside the house, crying yet again. I went in to milk my cows for the last time before I sold them. It was bittersweet; all I could see was loss surrounding me. I thought long and hard while milking about what kind of life I wanted for my daughters. I had thought that riches would bring them happiness. But Tzeitl had taught me otherwise. I thought that giving my daughters freedom from my judgments would bring them happiness, but Shprintze taught me otherwise. Yet again, I saw my daughter choosing a path that would break my closely held value of the family, and all that held dear to me. I finished my milking and went inside to talk to Teibl about what I had decided. With curses and laughter, the world does not change. I found her packing up her things in a small suitcase.

“Teibl, my daughter. I have thought about what you said to me. I see now that it is not about the future I see for you, but the future that God sees for you. It is not my place to tell you what your fate should be, therefor I cannot tell you no. It is your life’s duty to follow the path set for you, where ever it may lead you.”

Teibl again began to cry, but this time they were not tears of sorrow. She looked at me with a half smile on her face and threw her arms around my neck for a tight hug.

“My dear father, I fear that this is the path set for me. I have been given a chance and I cannot let it pass by. I have talked to my sisters. They agree that I should do what is best. I thank you deeply for coming to understand the same.”

“I fear that while I have come to accept your choice, my heart tells me that I cannot go with you. I will still go to Israel, with your sisters. I believe this is the best path for me, the one written in my fate. I hope that you too, can accept this as I have done for you.”

“I understand that we are on different paths now papa. If this is truly what you want, then I will meet Gluke and her family at the train station without you. While I will miss you terribly, this I can accept.

We set out in the evening by cart for Odessa. We had heard this was a good point to leave where we would not be detained. The cows and house had been sold; we carried with us the few possessions and clothes we had left. Oh how I wished my Golde could be here with us for this life-altering journey. I wanted to weep, thinking of all the memories of her I was leaving behind in my house. All the memories of raising our girls, all our years of struggle and strife to keep the farm, for what? I could not bring myself to look behind me at the house, as it grew more and more distant.

I reflected on all that we had done together as a family. I realized that the most valuable thing I had done as a father was prepare my daughters to make their own independent choices, and know what was best for themselves. I had raised them in a proper home, and given them the skills they needed to succeed.

Our journey was a long one, it took us days to reach Odessa. When we finally arrived there was a strange tension between the family. Everyone was apprehensive, waiting for what was to come next. We stopped at the market to sell the horse and carriage to make as much money as we could. I gave the profits to Teibl, for her journey. Somber and quiet, we all headed to the railway station to say our goodbyes. Myself and only four of my seven were starting out on train, while Teibl would head in the opposite direction and head West to catch a boat. We shared our final tears, hugs, and I love yous. I stared tearfully at my daughter while thinking about her future, and where God would take her. I knew that this was not our final goodbye; for we would be reunited by the good Father himself one day. “Scholem Aleheiem, Teibl.”

“Scholem Aleheim, Papa, thank you.”

And with that my little dove spread her wings and began to fly, we parted and went on our separate ways, letting fate guide us from here.

3. “A Daughter’s Prayer”

Found and introduced by Emily Erdmann

Introduction:

The following section of text is intended to represent the prayer of one of Tevye’s unnamed daughters, conveying her frustration and desperation with the treatment of Jews in the Russian empire around the turn of the 20th century. Her grievance is directed at the general mistreatment of her fellow Jewish people, but she is confused as to where to direct the blame: is the fault on God or humanity? This confusion is meant to represent the complex and disconcerting emotions felt by late 19th century Jews as they found themselves being “… punished by [their gentile] friends, for no reason at all.”[4] Regardless of the answer, be it God or flawed human nature, the fact of the matter remained that Jews were manipulated and helplessly subjected to the whims of the Russian Orthodox majority.

Forced to live in a specific region entitled the Pale Settlement, and to serve as the majority’s scapegoat, Jews found it difficult, if not altogether impossible, to merit respect in their European environment. According to Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, pogroms consisted of the persecution of the Jews for their alleged practices, meaning that an assumption was considered a sufficient and acceptable rationale for the terrorizing of innocent Jews. In reality, these mob-like outbursts served not as ‘an eye for an eye’ vengeance, but rather “… documentary evidence [showed that] the pogroms were deliberately organized by the czarist government to divert into channels of religious bigotry and ethnic hatred the Russian workers’ and peasants’ discontent with political and economic conditions.”[5] Their character was out of the question, a given Jew could be the nicest or the meanest man in town and either way he would be considered prey to a pogrom. With no control over their fate, the Jews became increasingly despondent, as Tevye’s family did, and so many others alike. Aleichem speaks through the Dairyman to say that “A Jew must [therefore] exist on hope and faith,”[6] because Jews at the time had nothing and no one else in their environment that could support them; the Jews had no one but their God.

Ultimately, history seems to attest to the fact that many Jews arrived at a state of learned helplessness, wherein they anticipated the next hardship, the next pogrom, the next eviction – whatever it was to be – as something that would inevitably befall them. Existing on naught but hope and faith proved to be an arduous request as misfortune followed misfortune. Tevye, exasperated, exclaims, “… if one tragedy happens, another is soon on the way … That’s the way God created His little world, and that’s the way it will always be—a lost cause!”[7] Tevye, despite being a proud Jew who loves scripture and puts his religion first, is still subject to this phenomenon of fading hope.

Aleichem was a religious practicing Jew, thus it is logical that his main character overcomes his brief bout of doubt as he proclaims near the end “… we have a powerful God and … a person, so long as he lives, should never lose heart.”[8] However, this renewed religious vigor was not the only response to the everlasting trials around the turn of the century. As a result of the Jewish Enlightenment (or Haskalah), which lasted from the late 1700s to the late 1800s, there was a gradually growing secular perspective that separated the religious practice of Judaism from its culture. Jewish Historian Shira Schoenberg notes that “The Haskalah was characterized by a scientific approach to religion in which secular culture and philosophy became a central value.” The rationality of this movement aimed to better integrate Jews into European society—a process that therefore encouraged interaction with non-Jews.[9] This secularization combined with external interactions and, later on, the tribulations of being used as a scapegoat, is likely to have contributed to the growing number of Jews identifying as secular. Data collected by the Pew Research Center suggests that this trend continued on through the 20th century, perhaps even more notably during the Bolsheviks’ years in power. Former Soviet Union Jewish emigrants to Israel were surveyed and found to be 81% secular. It is interesting to note that “Only 60% of second-generation FSU Jews say they are [secular].”[10] This seems to support the idea that experiencing religious persecution and suffering like that which was inflicted by Stalin contributes to a diminished religious inclination; on the other hand, without the same degree of prejudice, a greater number of the children of said emigrants were recorded as believing.

In short, the prayer below can be seen as a sort of alternate ending, one that attempts to show the inner turmoil and doubting perspective that might lead a once-devout Jew down a more laic path.

A Prayer:

O Father, where did we go wrong? Did You not command us to love the strangers living alongside us as if they had been born unto us?[11] Why did you “… create Jews and non-Jews, and why [are] they so set apart from one another, unable to get along, as if one had been created by [You] and the other not?”[12] You claim that all are equal in Your eyes and yet we are divided, disadvantaged, and persecuted by the very people we set out to love.

These pogroms have been an issue for other Jews recently, but I never would have thought that our neighbors—although they are Christians—who have forever treated us with kindness, could turn on us unanimously and without warning. Has Papa not worked for them long enough? When did he lose their respect?

Forgive me, for I know that You are supposed to know better than I what is best and what is to come. Yet I remain upset. “Why should people be so bad when they can be good? Why should people embitter the lives of others as well as their own when life could be sweet and happy for all? Is it a given that [You] created man in order to have him suffer?”[13] I fail to see how we are created equal and called to love thy neighbor even as said neighbor arrives, as the mayor did, informing Papa that although he is not a “bad person,” he is still a Jew, and because, in the gentile perspective, these two things have apparently nothing to do with another, Papa must be beat up for the latter.

“… [When] there is a rumor of a pogrom, Jews run from one city to another,”[14] so we are like caged mice, trapped in the Pale of Settlement. Father, where do we go from here? We are leaving the home we have lived in and loved, this harsh fact is certain, but is there anywhere You can guide us where neighbors won’t turn on neighbors and enemy is not distinguished from friend by the mere difference of a symbol?

Papa may endure on faith alone, but I don’t know how much longer the rest of us can last. As Jews, our life revolves around the law that is our service to You, acts of loving-kindness, and Your word in the form of the Torah.[15] But my acts and services to You have only brought me to my deplorable present state: evicted and on the brink of obliteration at the hands of a people towards whom my people showed nothing but love. With each new, negative development, I feel the Torah’s roots slowly withdrawing from the foundation of my life.[16] Papa always says that “… the more troubles you have, the more faith you must have, and the poorer you are, the more hope you must have,”[17] but this is more simply put than practiced…

Addison Caruso is a senior majoring in History.

Tessa Ralinowsky is a senior majoring in Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies.

Emily Erdmann is a junior majoring in French and Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies.

[1] Kenneth B. Moss, “At Home in Late Imperial Russian Modernity-Except When They Weren’t: New Histories of Russian and East European Jews, 1881-1914,” The Journal of Modern History 84, no. 2 (2012) 413.

[2] Stefan Wiese, ““Spit Back With Bullets!” Emotions in Russia’s Jewish Pogroms, 1881-1905,” Geschichte und Gesellschaft 39, no. 4 (2013), 477.

[3] Moss, 411.

[4] Page 120 of Aleichem, Sholem. Tevye the Dairyman. Penguin, 2009.

[5] “Pogrom.” Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia, 2017, p. 1p. 1. EBSCOhost, proxy.lib.miamioh.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=funk&AN=PO101600&site=eds-live&scope=site.

[6] Aleichem, 14

[7] Aleichem, 117

[8] Aleichem, 132

[9] Schoenberg, Shira. “Modern Jewish History.” The Haskalah, 2017, www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-haskalah

[10] Theodorou, Angeina E. “Israeli Jews from the Former Soviet Union Are More Secular, Less Religiously Observant.” Pew Research Center, 30 Mar. 2016, www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/03/30/israeli-jews-from-the-former-soviet-union-are-more-secular-less-religiously-observant/.

[11] Paraphrase of Leviticus 19:34: “The stranger who resides with you shall be to you as the native among you, and you shall love him as yourself; for you were aliens in the land of Egypt: I am the LORD your God” (NAS, 1977)

[12] Aleichem, 81

[13] Aleichem, 95

[14] Aleichem, 84

[15] Rich, Tracey R. “Love and Brotherhood.” Judaism 101, www.jewfaq.org/m/brother.htm.

[16] Tevye’s daughter is expressing difficulty in holding to her faith and the devout religious component of her Jewish culture. According to Eugene M. Avrutin, a professor of modern European Jewish history at the University of Illinois, Jews “… turned to Christianity as a last resort. [They] chose to convert for strategic reasons—to alleviate the existential burdens of Jewishness” (Jews and the Imperial State, 118). In other words, if Tevye’s daughter were to go through with such a conversion, she would conceivably be able to marry a Christian, thereby opening a door to more opportunities. Converted men in particular could hope to achieve a better education and a better job.

[17] Aleichem, 34-35.

UCLA’s Jewish Newsmagazine, Ha’Am, commented that a substantial portion of the Russian Jews that had once comprised the “Jewish Question” had “… [disappeared] into secularism” (Solovey, Mark, et al. “The Difficult History of Russian Jews.” Ha’Am; UCLA’s Jewish Newsmagazine, 14 May 2015, haam.org/2015/05/11/the-difficult-history-of-russian-jews/.)