Profile Text: Hunter Kolbus Editor: Sam Purkiss Audio: Joceline Medina

One of the first things Matthew Marroquín and his family knew about Storm Lake was the local Burger King. Not exactly fine local cuisine, but it would do. His family had come to town in 2000 because of the job opportunities available at IBP for his father, and the company offered them a hotel room while they sought more permanent accommodations. With his dad taking the car to work, Marroquín’s mother had to feed the family at restaurants within walking distance. Right next to the hotel was a whopper of fast-food fare, and after four weeks of the BK life, they were sick of flame-grilled haute cuisine. To this day, most of the Marroquín family avoids Burger King.

Matthew Marroquín’s family came to Storm Lake as the town experienced large growth in immigration, especially for the Hispanic community. As a young boy, he didn’t immediately notice the unique diversity in this Iowa small town. He did begin to notice some small oddities, though. “If I go over to this friend’s house, I have to say hello to their mother in this way,” he said, “and if I go to this [other] house, I have to learn [hello in] Laos or Vietnamese.” With age, he realized that there were differences between him and his classmates beyond just language. He started learning how different cultures celebrated holidays, and how some residents had holidays foreign to him.

What can I create to empower them [to] be the shakers and movers…not only within the school, but within the community?

As Marroquín matured and appreciated more of the diversity around him, he became involved in community and school organizations. One of the first was the National Hispanic Institute (NHI), an honor society. Through the NHI, he traveled to various events and conferences with other outstanding students of Hispanic descent. These events inspired him to think of ways he could influence other students to continue their education and engage in leadership training, so that they could contribute more to their communities. “But how do I also empower them, or what can I create to empower them,” Marroquín pondered, “[to] be the shakers and movers…not only within the school, but within the community?”

In 2018 he graduated and enrolled in Buena Vista University, where his activism grew. He joined Raíces, the university’s Latino organization. All this involvement helped Marroquín not only to raise awareness of issues affecting his community, but to empower those from diverse communities, his ultimate goal.

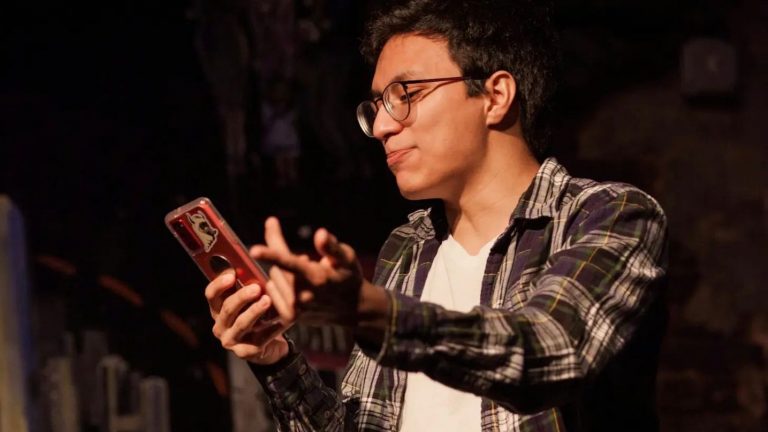

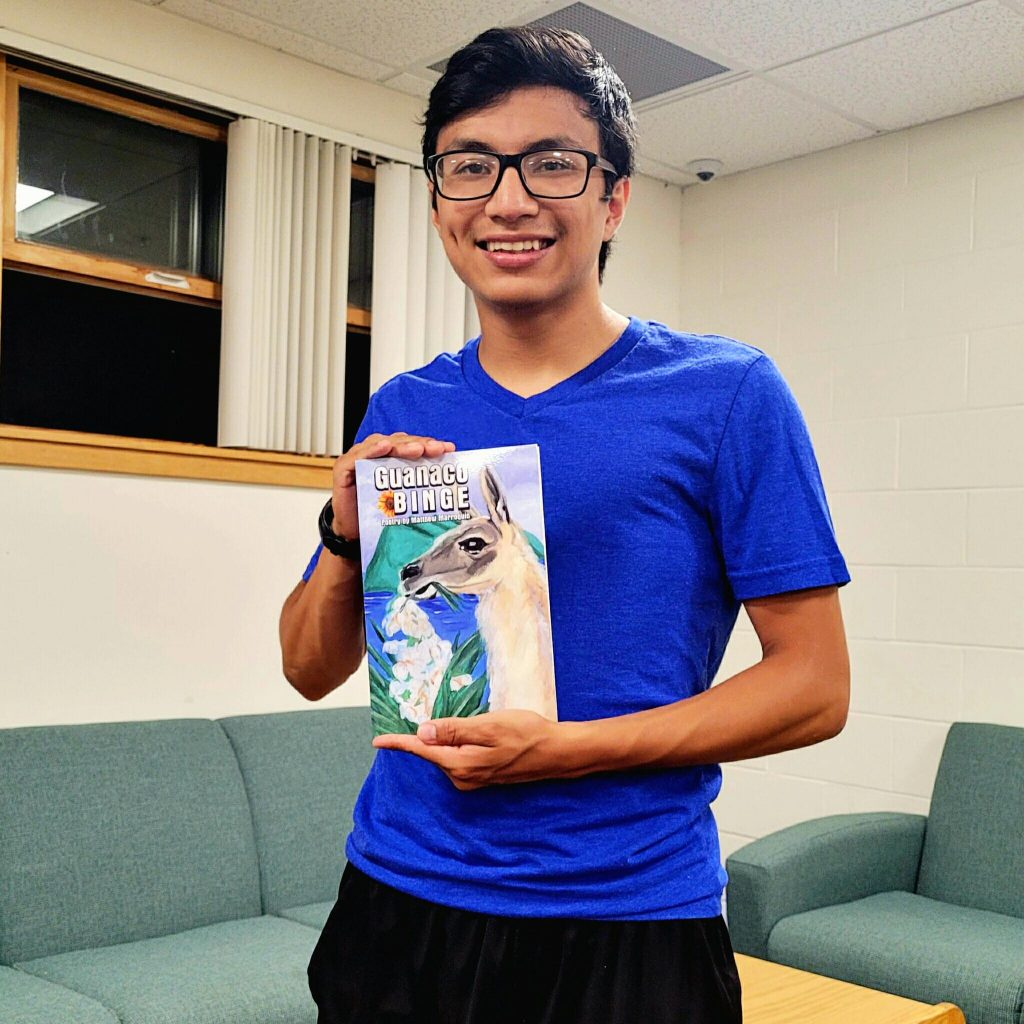

Marroquín has now graduated from BVU and has moved to the greater New York area to pursue his passion for writing. He has developed a love for slam poetry and has been writing and performing some of his own work. One of his poems focuses on the hardships that immigrant families have to endure when coming to America, and contrasts this with an idealistic view of America that many people have. “They force you to trade your linked fingers for linked chains,” Marroquín recently recited. “Your mother’s warmth for foil blankets. Your father’s strength to take care of another child, who is not yours, but simply came to this country just like you. This is America, where surviving was supposed to mean thriving…The place that you do not know. The place that is not your home and they make damn sure that you know that, too.”

One of the challenges that BVU faces is trying to integrate its community with the larger Storm Lake population. Marroquín once tried to put on a Latino gathering, but when the community members arrived on campus, they got lost because they had never set foot there before. Some residents claimed there was nothing for them. “So, there is no community engagement when it comes to, ‘Let’s bring people here,’ or ‘Let’s go out with them,’” he said. He did express some hope about this issue, though. “Now they’re starting to try to build that up and they’ve been saying that for years now. Trying to build that connection, but it’s just been hard.” He also remarked that it’s a challenge to work around some of the community members’ schedules, especially those that work at the Tyson plant, because of the strict working hours.

[T]here is no community engagement when it comes to, ‘Let’s bring people here,’ or ‘Let’s go out with them.’ . . Now they’re starting to try to build that up . . . Trying to build that connection, but it’s just been hard.

BVU’s racial diversity is below the national average with 82.1% of the undergraduate students being white, and for Marroquín, this was a shock coming from a high school so nearby, where Hispanic students make up the majority (51%). In one of his first classes at BVU, Marroquín walked in and realized he was the only person of color in that class, and that the white students might expect him to talk about his own diversity as well as minority identities that are not even his own. He also learned that some of his habits, like talking in a combination of Spanish and English, were not the norm in this new community. “Even at Storm Lake, the high school, I could talk Spanglish and people would understand me because half of my people are Latinos” Marroquín said. “I’ve never been called out before for intermixing my languages until I came to BV.”

Outside of his involvement within the university, Marroquín tried to be as involved with the Storm Lake community, which caused him to confront some of the biggest challenges the city faces, such as the presence of Tyson. After all, it was the original reason the Marroquíns came to Storm Lake along with so many other families. “Everybody knows somebody who works at Tyson. Everybody,” Marroquín said. “It’s either your parents, your uncle, your aunt…Just, somebody related to you works at Tyson, probably.” Although Tyson has become a mainstay in the community, there are still issues with the diversity among upper management. Marroquín’s summer job at the Tyson Feed Mill opened his eyes to these issues. He recounted that he and other feed mill workers were forced to park in the back of the parking lot and were not able to walk through the front offices, offices filled with mostly white workers.

Despite the challenges that Storm Lake faces, Marroquín still loves and gives back to this community that helped him become the person he is today. He still recognizes the value of “Iowa Nice,” the idea that Midwesterners are inherently kinder to one another, and how important diversity is for the community. “I would not mind raising my family in Storm Lake,” he said proudly.