Profile Text: Charlotte Moore Edited by: Sam Purkiss

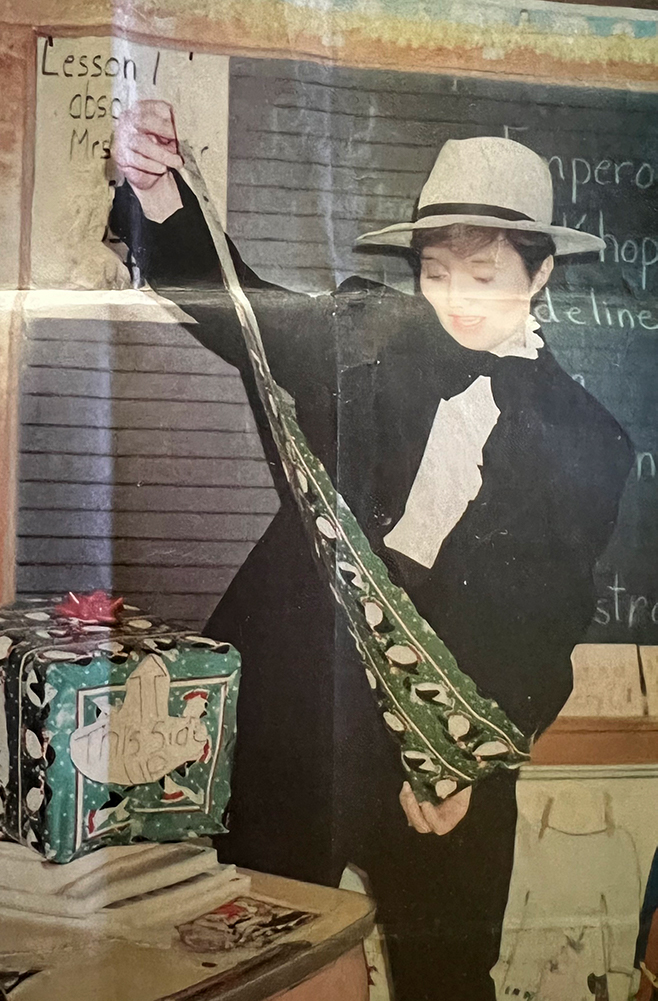

There she stood, decked out in a black and white tuxedo, pretending to be a penguin. Jan McKenna waddled before a class full of young kids, hoping the ruse would somehow help her students learn the day’s lesson. “Everybody learns differently,” she said, laughing at the memory.

By dressing up like a penguin, McKenna made herself vulnerable to giggles in exchange for some energy from the students, and therefore crossed the line from being a good teacher to a great one. At other times, she would do a Hot Air Balloon Unit, a “Hog Wild” Unit, as well as others on rainforests, city government, and space. “One of our biggest accomplishments was ‘Thumbs Up for Reading,’ which had the students stay overnight at the school and do Reading Activities,” she recalled. “What an undertaking, but so much fun.” In 2008, she was recognized as the Walmart Teacher of the Year in Storm Lake.

McKenna began teaching at St. Mary’s Catholic School in 1985 as a third grade teacher. After a few years of dedicated and personal involvement with the school board, McKenna applied for a teaching position with the Storm Lake Community School District in 1989. Up to then, she had been advocating for educational opportunities on a board primarily concerned with the logistics of staffing, budgeting, and finances, but she recognized that her fellow teachers and other leaders “were awesome,” she said. “My leadership [team] was absolutely phenomenal. I had terrific superintendents, terrific principles, and a great team.” With a subsequent masters in education from Buena Vista University, she began to thrive within Storm Lake’s public school system and eagerly accepted any opportunity to advocate for children’s educational welfare.

In the classroom, McKenna liked to encourage her students to learn about things that they would encounter in their own lives and in Storm Lake. With the help of her husband, Kevin, she brought students a bale of hay from their family farm, a seemingly disruptive thing to a classroom, but in reality it allowed for a connection between school and home. Students “could roll [the hay] around, and they get to feel it and smell it, because we did have a wild unit, and they wonder what you could sleep on, so I had Kev bring in a whole, big roll.” She even brought her students out to her farm several times, showing them the animals and equipment. All of this allowed for a wider scope of what “learning” meant to them, beyond mere mathematics and language lessons.

McKenna also described a tactic and strategy that she and her co-teachers would use in their classroom. They would send “home a stuffed animal every weekend,” she said, “and every weekend a child took a journal and they could give [the stuffed animal] any name they wanted and they had to write about everything they do with that animal like. They would take it to grandma’s house, they take it to the grocery store, they sleep with it…” When the students would return to the classroom, they would share what the stuffed animal did that weekend, giving the teachers insight into their students beyond the classroom in order to better support and understand them in school. Such innovation deserves praise in isolation, but McKenna has made a whole career out of these delightful learning opportunities.

McKenna also recognized that a vital part of developing the SLCSD would require coordination and collaboration with parents and the community at large. While trying to find a compromise between the needs of the students and the limits of the school’s budget, McKenna–like many other teachers at the time–contributed personal funds, effort, and love to her school in order to address immediate needs. She also noted how her coworkers were equally dedicated to their jobs. They truly loved the students that they were able to raise.

With any job comes challenges. For Storm Lake teachers, McKenna noted, it was the introduction of a diverse array of immigrant cultures to the classroom. She remarked, “When I got done teaching I had two or three different languages — in my classroom. I think now there might be up to fifteen or eighteen. I’m not sure. But they come from little countries that you maybe wouldn’t have heard of. The biggest problem we have is getting someone that will speak [their] language. That’s the difficulty.” McKenna made a point of how diversity can be a mutually beneficial relationship between people: “Those children bring things to us and help us to grow with their cultures and their backgrounds…that’s a wonderful thing,” she said.

McKenna has shaped the lives of her students and peers. She spoke fondly of memories about a former student-teacher of hers, the current superintendent of Storm Lake City Schools, Stacey Cole. Cole models a great example of a community based participatory model of education, focusing on meeting community needs in time with accomplishing broader goals set forth by curriculums and state guidelines. By working with and enacting community actors and leaders to engage in interconnected conversations, where residents and parents are a part of the research process and assessing community needs, the district is able to come together, find, and work with resourceful partners.

This community-based approach to education and the SLCSD at large has been in place and created an environment conducive to accepting more and more diversity while enabling growth and change in the curriculums. Her children went through the school system, and now her grandchildren are going through it with very different demographics and circumstances.

McKenna stands as an example of a person whose life has been dedicated to her students, family, and community. She did mention one regret from her time in Storm Lake schools: “I wish [that I learned] Spanish, because I could have been so much more of a benefit to this community,” she said. The language challenges also revealed, to her, the burdens her students faced. “I mean, I know a few words here and there,” she said, “but a change in the reverse is they are learning a lot of English now…I always had my students come to the [parent-teacher] conference because they were good interpreters. They were. I mean, it humbled me, because I’d sit there and wonder what they said to the parents. And I said, “Okay, tell me what you told them,” because they would turn to them and say it in Spanish, turn around and listen to me in English, and then turn around and say it to them in Spanish.” Ever the educator, ever the student.

Currently, McKenna is looking forward to the next chapter of her life, with her retirement now nine years behind her. She is excited to spend more time with her three children and ten grandkids, to work with her husband on their land, and to enjoy the town and its lake, especially now that she can see former students growing into their own community roles.