By Kara Reedy —

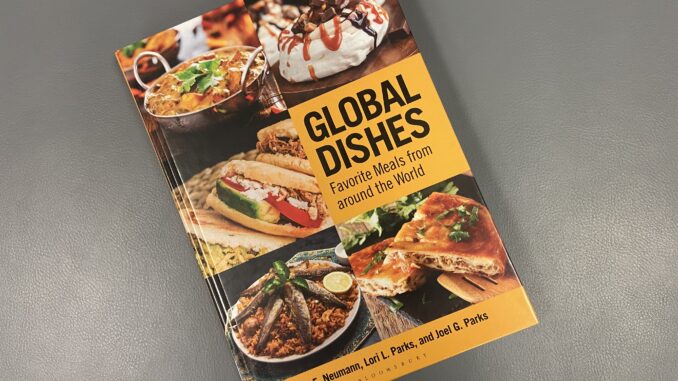

Recently, there was a special day for Doctors Caryn Neumann and Lori Parks, who wrote Global Dishes: Favorite Meals from Around the World, with the additional expertise of culinary artist and Executive Chef Joel Parks. Their book details many favorite foods from around the world; American, Greek, and Iranian cuisines are examined among one hundred other countries. Their presentation on Middletown’s campus discussed the book at length, focusing specifically on what makes a national dish.

According to the authors, a national dish is more than just ingredients. A dish can be deemed “national” depending on its “affordability, tradition, and political status” in the eyes of its people. History has extensive influence over the perspectives of people, and nowhere is that more visible than in the foods of the world. Our connection with food reaches beyond our differences, bringing us all together in more ways than many of us may comprehend.

American cuisine is particularly fascinating, given how much other cultures and communities have influenced it, but what comes to mind when you think of America’s national dish? You may think of hamburgers or something similar, but such a distinction is not so easy when the diversity of American culture is taken into consideration. So, what do you think of as a “regional” dish? Chili may come to mind. Perhaps Cheese Coney’s? The Cincinnati area is famous for its spin on the dish, but do you know where the original concept for the dish comes from? Chili comes from near Mexico and Texas, and has taken on many different forms, with many arguing that the best chili has beans, corn, or even chocolate, depending on the region. Immigrants from Greece created the Coney as a transfusion of Greek cuisine into an American classic: the hotdog. Coneys were served cheaply by vendors looking to make their way in this country, fitting the affordability requirement of Doctor Neumann and Parks’ model for the national dish. The foods we call ours often originated from the minds of others from all over the globe, and America isn’t the only example of this occurring.

Tomatoes and potatoes were originally from the Americas, yet both feature prominently in the national dishes of countries across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Dizi, also known as abgoosht in some places, is an affordable Iranian dish containing “inexpensive cuts of meat,” “chickpea stew with spices,” and tomatoes. Ireland is often associated with potatoes, but they are found in countless dishes across the globe, including Great Britain’s national dish, Fish and Chips.

The main thing these dishes all have in common is how cheap they are. Affordability accounts for accessibility, which, in turn, ensures notoriety among the wider public. There are also traditional foods that are considered nationally recognized dishes. The Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) biscuits—which Americans might view as cookies—are considered a traditional food in Australia. Anzac biscuits were created as an alternative to others that might have eggs in them, as those who baked them wanted them to last long enough to make it to soldiers on the front lines in World War I. Australia and New Zealand have another traditional dish that has caused some controversy over its origin. The Pavlova, which is a desert that is light and fluffy with an assortment of fruits, was created to honor the Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova, who spent time touring the countries.

Even politics has a way of seeping into many of the foods we eat, causing arguments over the origin of dishes in some cases and sometimes even bringing about celebratory dishes that bring attention to momentous accomplishments. Soup Joumou is a Haitian dish that heralds the independence of Haiti from France following their revolution, which ended on New Year’s Day in 1804. The soup was reserved for French enslavers who kept the Haitian people from enjoying it. Following the victory for emancipation and freedom, the Haitian people reclaimed the soup, making it a dish for themselves to celebrate their win. Soup Joumou continues to be served on New Year’s Day in Haiti and remains a symbol of freedom from enslavement.

Food can also bypass cultural and physical barriers, tying the world together in ways that other means cannot. The foods we’ve come to love that we define as unique to our countries have never truly been separate from every other country; food exists as an amalgamation of diversity, and what we love wouldn’t have ever existed without it. Trade and persistent relationships across borders and over seas have ensured that our food will continue, as it always has, to intermingle, creating new dishes that we will come to see as national dishes in their own right.

The Gardner-Harvey Library continues to host an extraordinary collection of events which never ceases to impress and intrigue the Miami Middletown community. The Pulse News has happily reported on many of these events at the library since its beginning only a year or so ago. The organization looks forward to continuing its coverage of everything happening at the Gardner-Harvey Library, with the hope that the entire Miami community can continue to attend these events. If you ever have any questions concerning presentations held at the library on the Middletown campus, get in touch with librarians John Burke and Jessie Long. The next presentation will be held on Tuesday, November 28th, and will be led by Dr. Tammie Gerke, who will be discussing Yellowstone National Park. It will be the third and final installment of her National Parks Talk Series this fall. Keep an eye out for the story in the coming weeks.

Contact Information:

- Caryn Neumann – neumance@miamioh.edu

- Lori Parks – parksll@miamioh.edu

- Jessie Long – longjh@miamioh.edu

- John Burke – burkejj@miamioh.edu