Issue 1

The first issue of Journeys into the Past features eleven essays, four historical journeys, and one opinion piece (in a section entitled “Past and Present”). We will […]

Read More

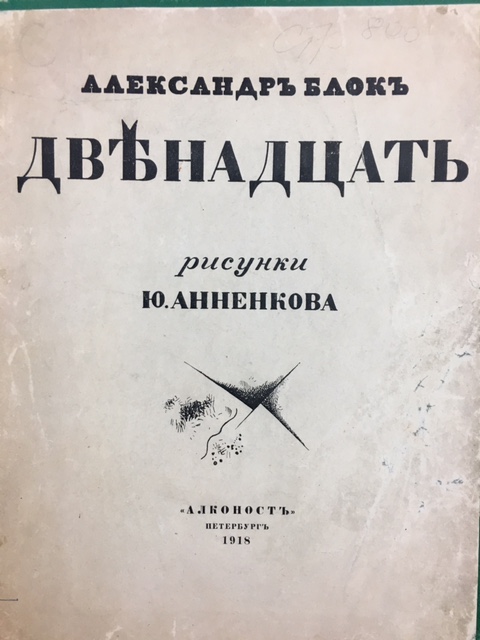

By Jake Hensh Блок, Александр. Двенадцать. Blok, Alexander. The Twelve. Oxford : Miami Special Collections, 1918. Throughout the Havighurst Colloquium series on “Russia in War […]

Read More

By Emily Oneschuk The following documents were the basis for this paper and can be found in the De Saint Rat collection of the Havighurst […]

Read More

Fig. 1, Album of Revolutionary Russia Cover. By Riley Kane DK265.15.A43 1919 Al’bom revoliuitsionnoi Rossii = Album of Revolutionary Russia. [New York] : Russian Socialist […]

Read More

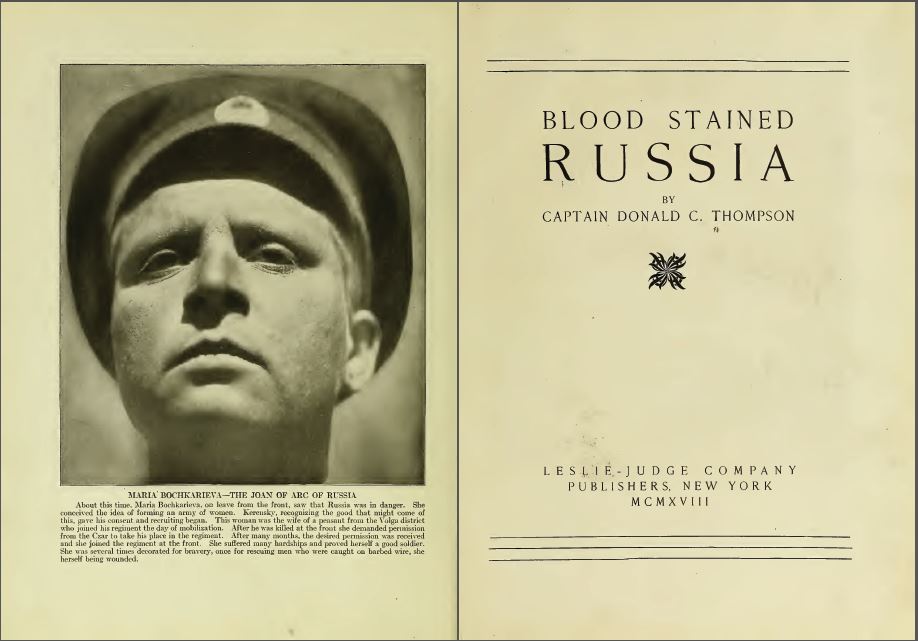

By Courtney Misich DK265.15 .T46 Thompson, Donald C. Blood Stained Russia. New York : Leslie-Judge Co., 1918. This medium-sized, red book, Blood stained Russia, offers […]

Read More

Smert’ Kommandera Pashkevicha. 1920. Photographs, 1917-1920s. Miami University Special Collections. Oxford, OH. The Death of a Revolutionary: Commander Pashkevich To most European nations, the […]

Read More

By Heidi Hetterscheidt Beginning with Peter the Great, the Russian Empire became increasingly influenced by numerous Western influences and ideas; however, Russian elites exhibited a […]

Read More

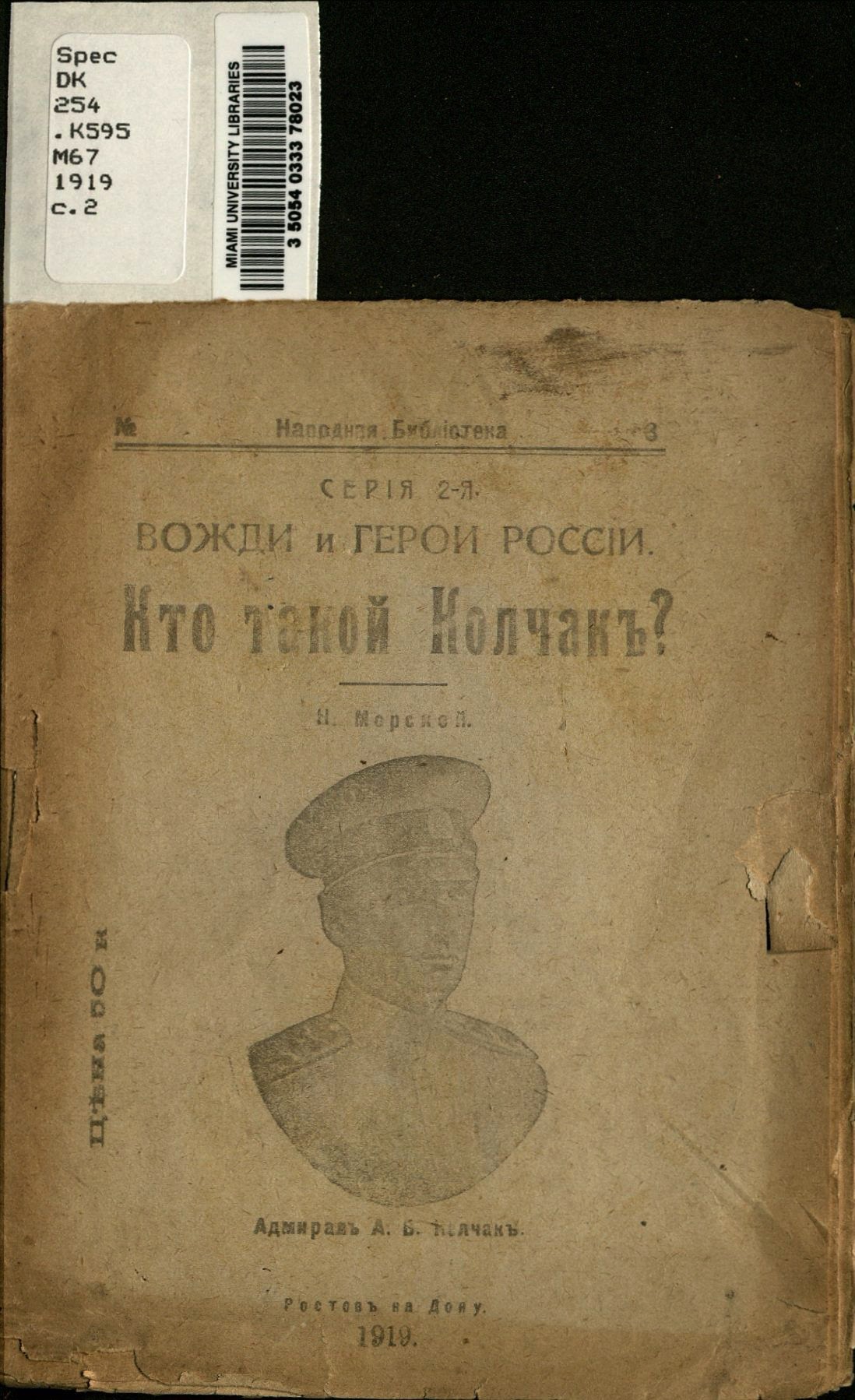

By Anna Melberg DK254.K595 M67 1919 Morskoĭ, N. Kto takoĭ Kolchak. Rostov-na-Donu : [s.n.], 1919. Morskoy, N. Who is Kolchak? Rostov-na-Donu: [s.n.], 1919. Kolchak: […]

Read More

By Colin Sullivan Admiral Alexander Kolchak was a true patriot of Russia and a hero to those of the White forces during the Russian Civil […]

Read More

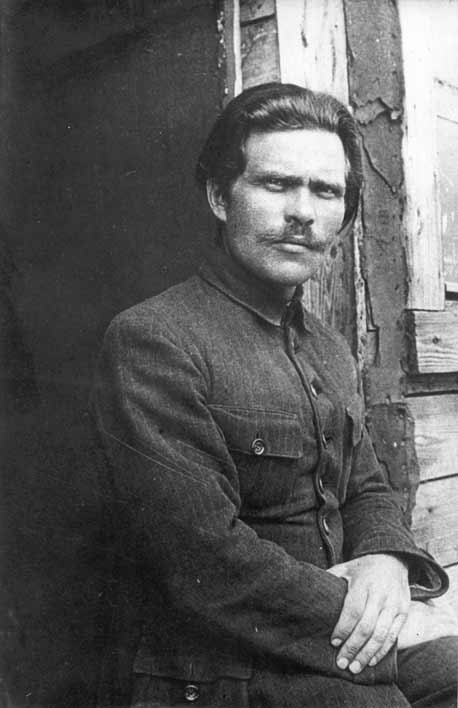

By Adam Rodger Makhno, Nestor Ivanovich, and M. I. Kubanin. Makhnovshchina i ee vcherashnie soiuzniki-bol’sheviki; otvet na knigu M. Kubanina “Makhnovshchina.” n.p.: Parizh: “Biblioteka Makhnovitsev,” […]

Read More