Volume I

Honors students enrolled in Dr. Stephen Norris’s Russian Revolution class transformed the Upham Room in Upham Hall into a propaganda room. Half of the students, […]

Read More

The second issue of Journeys into the Past builds on the first, which featured writing from students in a course on Russia in war and revolution. The […]

Read More

John Singelton Copley, Portrait of Mrs. John Stevens, 1770-72. By Jacob Bruggeman Devotees to the study of history are quickly becoming a bygone breed. In […]

Read More

Note: Students in Stephen Norris’s Spring 2017 class, Introduction to Russian and Eurasian Studies, participated in a final role-playing exercise that asked them to plan […]

Read More

Note: Students in Dr. Stephen Norris’s Spring 2017 class, Introduction to Russian and Eurasian Studies, read Boris Dralyuk’s recent edited collection of poems from the […]

Read More

Note: On February 2, 2017, students in Stephen Norris’s Spring 2017 Introduction to Russian Studies course engaged in a role-playing exercise that aimed to replicate […]

Read More

Mark D. Steinberg, The Russian Revolution, 1905-1921 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017). 388. Review by Jacob Bruggeman Mark D. Steinberg’s new book, The Russian Revolution, […]

Read MoreThe first issue of Journeys into the Past features eleven essays, four historical journeys, and one opinion piece (in a section entitled “Past and Present”). We will […]

Read More

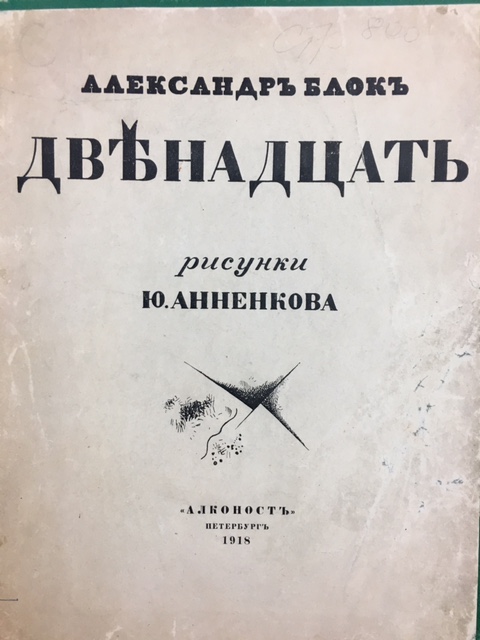

By Jake Hensh Блок, Александр. Двенадцать. Blok, Alexander. The Twelve. Oxford : Miami Special Collections, 1918. Throughout the Havighurst Colloquium series on “Russia in War […]

Read More

By Emily Oneschuk The following documents were the basis for this paper and can be found in the De Saint Rat collection of the Havighurst […]

Read More