The Haskell Boys of Battery B

By Jaden Singh

Last summer, Dr. Cameron Shriver sent me a 1,214-page PDF file, sizing up to one and a half gigabytes. This file contained all issues of The Indian Leader from 1917 to 1919, a magazine published by Haskell Institute, a Native American boarding school. He provided this source for my ongoing research on Native American participation in the First World War, where over ten thousand Native Americans served in the United States military, despite many of them lacking citizenship. I have used these materials to demonstrate how boarding schools often encouraged and even promoted military service as an opportunity for their students to demonstrate their patriotism; however, for now, I wish to discuss what I know of a small batch of students-turned-soldiers: the Haskell Boys of Battery B.

I had first come across these men shortly after delving into The Indian Leader. In three issues, the magazine included lists of Haskell students who were serving in the military. Finding these lists was exhilarating, as it had felt as though I had discovered something; I was not simply reading another scholar’s work or digging through an author’s footnotes- I had found this myself. Although I would later come to realize that, even in the extremely sparse research present on this topic, I was not the only one to consider The Indian Leader as a potential source, I felt very elated in the moment.

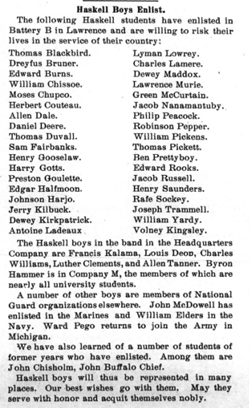

The list containing the men of Battery B is the first chronologically, but the only one to tie names to a specific unit, even though “Battery B in Lawrence” is vague by itself. Nonetheless, the article is still noteworthy, highlighting the pride the magazine aimed to convey with the mention of the students’ willingness to “risk their lives in the service of their country” and wishing them the best as they do so.[1] Still, the article raises several questions: what was service like for these men? What did they think of their service? And Battery B of what?

The chance to partially answer some of these questions arose during my visit to the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at Indiana University. This museum housed the Wanamaker Collection, a trove of material pertaining to Native military service in the First World War originally compiled by Joseph Dixon, a white photographer turned activist of the era.

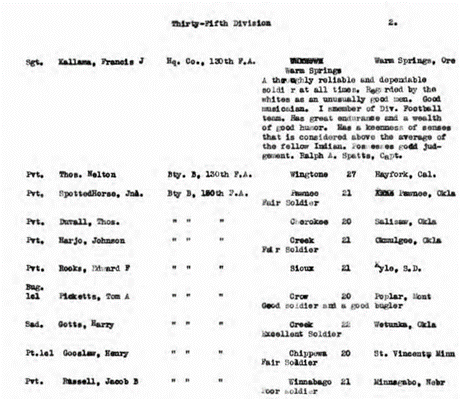

The first source of note from this collection are military records that intended to compile the results of a survey conducted on officers about their Native soldiers. Through these records, Battery B became Battery B of the 130th Field Artillery, 35th Division. Little commentary is provided by the officers reporting on the soldiers of this unit, but twenty-five out of the thirty-three soldiers listed received some sort of notation. Nine are said to have been fair soldiers, eight are said to be good, four are said to be poor, and the remaining four are said to have been excellent.

While not as evident within the record on Battery B, many officers viewed their Native soldiers as having inherent strengths and weakness due to being Native American; while a common criticism of these soldiers was their deficiency in speaking English, operating mechanical devices, and adhering to military discipline, they were often praised for their endurance, courage, and being ideal for scouting and night work. Praising and criticizing their Native soldiers in such ways suggest that officers adhered to the popular imagination of Native Americans: natural, but uncivilized, warriors. While this racialized element is not as present in the records of Battery B, the affirmative commentary that was provided by officers alludes to the fact Natives were often viewed positively as soldiers.

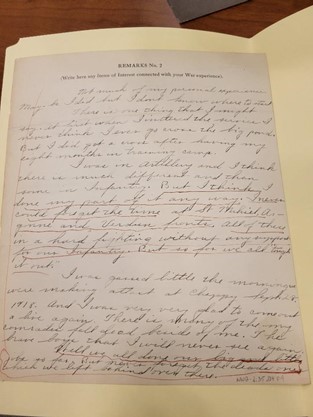

A second source from the Wanamaker Collection are the “List of Indians in the World War” questionnaires, which Dixon had distributed to Native communities and veterans, asking for details relating to their service, to support his effort of securing Native American citizenship. Of the 1,361 questionnaires, 849 were filled out by government employees, containing demographic information but often lacking personal commentary from the soldiers; however, over five hundred were filled by veterans or their families, some of which do provide commentary. Some of the soldiers in Battery B filled in questionnaires and did write on their service- one such soldier was Benjamin Prettyboy, who personally filled two questionnaires. In one, he writes of his experience during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive: “[They] gave us Hell but we give them double Hell … We the artillery men’s were catching hell during that drive.”[2] Jacob Nunomantuby wrote “My great experience in the World War” followed by a list containing the dates of “battles, engagements, skirmishes, expeditions” he had participated in.[3] Similarly, Jacob Russell wrote of the battles he was in, stating that he would not “[forget] the time at St. Mihiel, Argonne, and Verdun.” Adding to this, he asserts “There is many of the my comrades fell dead beside of me. (sic) The brave boys that I will never see again.”[4] Although mourning, the fact that Russell, and other soldiers who filled in questionnaires, were willing to contribute information indicates that they had felt pride in their service.

There is much that cannot be learned from Battery B alone. How did their militarized education from the boarding schools contribute to their training in the army? Did they encounter any prejudice from white soldiers or officers? What did their families think of their service? While Battery B may not answer these questions, we are lucky that the unit and its soldiers still left a paper trail. Through it, we can glean some parts of these soldiers’ backgrounds: the education they received, how their school and officers perceived their service, and how they themselves came to view their presence in the military. In doing so, the memory of this unit and the men within it, alongside their unique status as Native American soldiers of the First World War, can be preserved.

The Wanamaker Collection is currently located at the Indiana University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology; all materials from the collection were photographed and used with the permission of the IUMAA.

[1] “Haskell Boys Enlist,” The Indian Leader, September 14, 1917, 3.

[2] WWQ.di35.098:4, Wanamaker Collection, Indiana University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

[3] WWQ.di35.084:4, Wanamaker Collection, Indiana University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

[4] WWQ.di35.104:4, Wanamaker Collection, Indiana University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.