Personalizing Miami’s History: James T. Titus

By Brittany Vonkamp

From its introduction to North America in the Seventeenth Century, slavery was an important aspect of society, culture, and the economy of the growing United States. Over time, slavery became more and more enmeshed in American life. At the same time, Americans were building their colonies and ultimately their country, to where they relied less heavily on Britain and foreign aid, including the establishment of colleges and universities across the colonies/country. Craig Steven Wilder argues that higher education in America reflects the nation’s deep ties with slavery, and as the nation was built to be so intertwined with slavery, so too were these colleges and universities – of which many are still prominent today. Wilder also outlines the imperialistic ideals surrounding the nation during this time, as Americans were building their new nation and expanding westward, relocating Native Americans along the way and moving slavery with them. The life of one student, James T. Titus, and his family serve as a case study to see how Miami University had those deep ties to slavery and to national imperialistic ideologies.

Although Ohio entered the Union as a free state in 1803, Miami University – chartered in 1809, and classes beginning in 1824 – was an institution of higher education that began in the midst of American expansion to the west and at a high point of slavery in America. Located in Ohio, Miami was not a part of the south, but at this time was on what would be considered the frontier of America. The University was an active participant of the nation’s movement westward, making opportunities for higher education on the frontier more accessible. The new profitability of cotton following the invention of the cotton gin, though, led to the spread of cotton across the south, ultimately allowing for slavery’s spread across this region as plantation owners needed more labor to produce the cotton.[1] This increased production of cotton and slave labor became important in aiding the financial stability of many universities. For example, Miami and other schools in the Midwest were “constantly teetering on the edge of financial disaster,” and financially relied on students’ tuition money, as “the state did not appropriate money regularly” to Miami until 1896. Wilder exhibits how, at this time, excess wealth was used to fund a students’ higher education, and that excess wealth often came as a result of slave labor. Thus, while Miami participated in American imperialism to the west, it was also “attracting students from [both] the Midwest and South between 1824 and 1873,” and, as college was “reserved for the sons of elites,”[2] it remains likely that many of those southern students’ tuitions (leading up to the Civil War) were paid from an excess wealth from slavery – including that of James T. Titus.

The Titus family first arrived in America in 1635, with Robert Titus on the Hopewell, (which sailed in the same fleet as the Mayflower) coming to New England with the migration of Puritans from England. Wilder highlights how “the Puritans quickly adopted slaveholding [when] the plantations were so profitable that an enslaved African paid for himself or herself after only eighteen months.”[3] Because of this, it is possible that the Titus family had their hand in slavery by the late 1600s. Slavery in the Titus family can be dated at least as far back as James’s great-grandfather, Ebenezer Titus, who purchased an enslaved girl in May of 1797.[4] As a part of the westward imperialism Wilder discusses, Ebenezer moved to Tennessee during its first settlement in Davidson County around 1780,[5] when the land was still part of the North Carolina territory, and where he was given a land grant in 1787,[6] on which he built the Dry Creek Plantation.[7] Other “Bill of Sale” records show Ebenezer’s purchase and sale of slaves as well as some stating the gift of slaves to his children – including gifts to the grandfather of our Miami student, James.[8] Along with the gift of slaves, Ebenezer also divided his plantation among his children upon his death, though the land was eventually sold off.[9]

Ebenezer’s son, James, the grandfather of James T. Titus, also played an important role in the Titus family’s connection to slavery as well as national imperialism. Although he sold the land passed to him from his father, James Titus moved to the new Mississippi Territory (present-day Alabama) in 1809, where he became a prominent figure in society there, as a captain of the Mississippi Territory Regiment, a member of the Mississippi Territory Legislature, and eventually “the sole council member for the entire first Session of the Alabama Territory Legislative Council.” Ultimately, after assisting Alabama’s government to statehood, James moved his family back to Tennessee in 1824 and specifically to Shelby County, Tennessee in 1836.[10] Here he owned 2,800 acres of land, worth $11,200 and sixteen slaves, worth $7,500 by 1837.[11]

In Tennessee, James was hired by the federal government to assist in President Andrew Jackson’s plan for “the immediate and complete removal of Indians to areas beyond white settlement”[12] under the Indian Removal Act of 1830. This relocation of Native Americans later became known as the “Trail of Tears.” By 1839, though, James Titus had settled in Texas with his son Andrew Jackson Titus, where he had received a land grant and built a plantation.[13] Here he opened the first post office of Clarksville, Red River County.[14] James “was one of the oldest [and] most respectable residents of [Shelby] County…[and] was well known both in [Tennessee] and Alabama.”[15] Upon his death in 1843, he willed his Texas plantation and his slaves to his wife and children. James’s son, Frazior Titus, the father of our Miami student, in addition to a piece of land, was given “a Negro boy between the age of twelve and fifteen to be bought for him out of the money coming to [James] from the state of Tennessee.”[16]

Frazior Titus was a member of a prominent Tennessee family, and remained a member of that elite class into his adulthood. For many years, he held position of alderman in Memphis local government [17] and also served as President of the Committee of Safety for the city, particularly during the Civil War, as he sympathized with the Confederate cause.[18] Being over sixty years old when the Civil War began, Frazior did not fight in the Confederate army, but many – if not all – of his sons did, but he still supported the Confederacy through his position in Memphis government. Even before the outbreak of war, Frazior signed the “Memphis Secession Directory,” on February 26, 1861, supporting Tennessee’s secession from the Union.[19] However, before the war officially came to a close, Frazior did take an oath of allegiance to the United States, and was later pardoned by President Andrew Johnson on August 14, 1865, for the role he played in the war.[20]

Not only did he actively participate on the confederate side of the Civil War through his position in local government, Frazior Titus was also a prominent businessman of Memphis. In 1850, he funded and built the construction of the first apartments in Tennessee on what was known as the “Titus Block.”[21] In addition to the apartments, Frazior also played an important role in the slave society of the south, as he owned at least twenty slaves by 1860 – “placing him in the top ten percent of slave owners”[22] – was a wealthy cotton factor and merchant who owned a Cotton firm, Moon, Titus & Co.,[23] and was director of the Memphis and Ohio Railroad in 1860.[24] Although Wilder’s argument focuses more on colonial merchants when he says they “became the patrons of higher education,”[25] the idea holds true after American independence as well. He later claims that “merchants and manufacturers with economic ties to the cotton and sugar plantations of the south and the Caribbean transformed higher education in the antebellum North,”[26] – this transformation being a tuition based on slave money, which ultimately helped fund the institution and then influenced the content that was taught, including the concept of “race.” Holding these strong ties to cotton, and subsequently slavery, as Wilder suggests, Frazior Titus likely played a hand in this transformation of higher education in the North by sending his son to Miami University.

That son, James T. Titus, was born on December 24, 1836, in Tennessee to Frazior and Louisa Ann Edmondson Titus, and James T. attended Miami University around 1852. While not much else is known about him or his time at Miami, speculation can be made about his life through the records of James’ family. Through these records, it is clear that this Miami student did come from a prominent elite family in Memphis, Tennessee, supporting the “sons of elites” notion surrounding colleges during this period. He grew up in a household, family, and society where slavery was an important aspect of life, and imperialism was a strong belief. His grandfather helped expand the nation west to include Mississippi, Alabama, and Texas, and later his father was both a wealthy slave owner and important player in the cotton industry of Memphis. Like many other young men, Titus likely learned values and ideals during that time, coming to age, that he later carried with him as he attended school at Miami University. He may even have debated with other students based on those values and ideals during his time at Miami, where students, especially in the Literary Societies were discussing and debating the current events and rising tensions of the nation.[27] Although Titus only appears once in records of Miami students, when he is listed in the 1852 catalog as a student in the Preparatory Department,[28] he at least spent some time at the university, where he could have shared his beliefs with others and gained new perspectives from his peers.

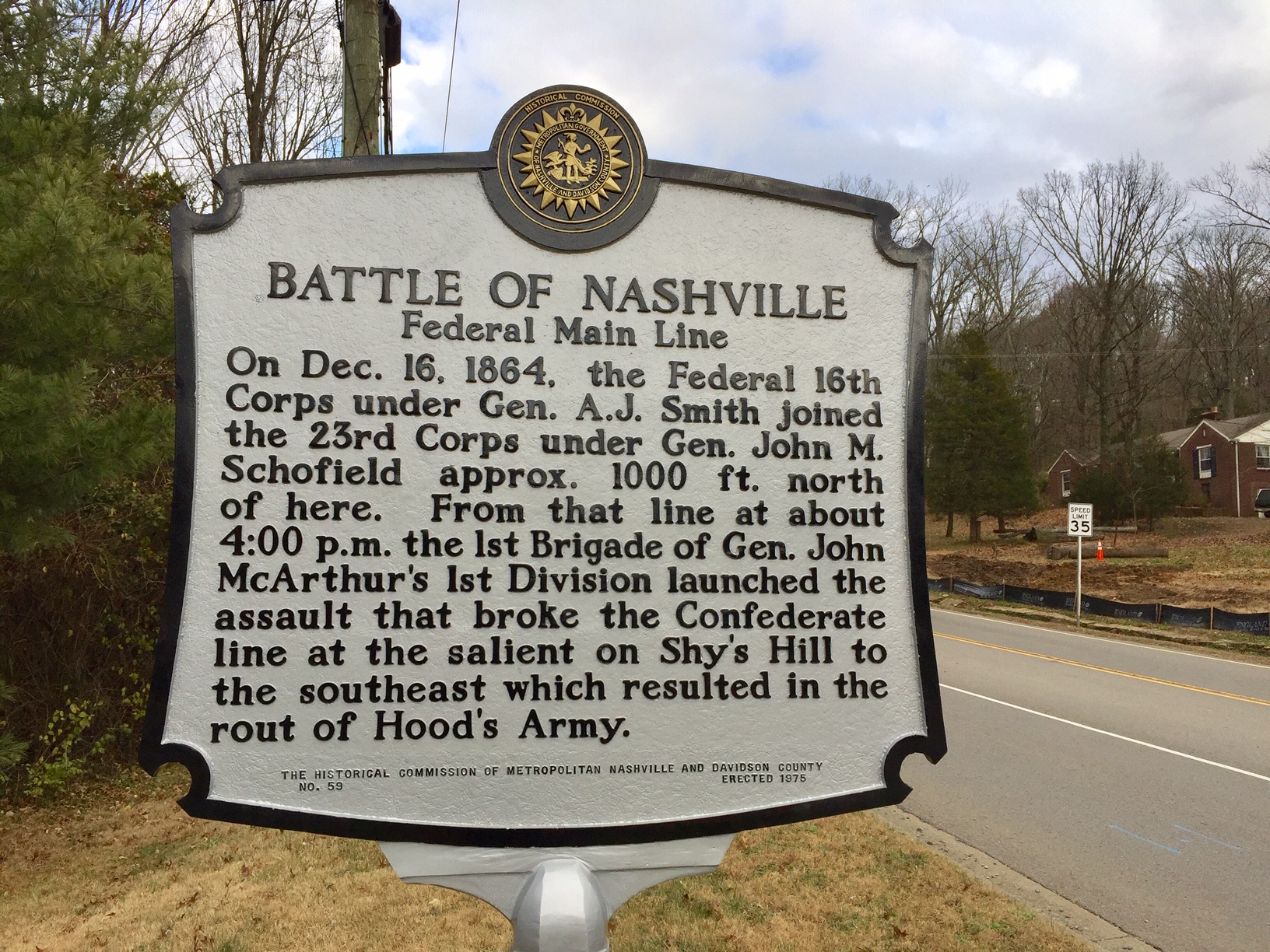

Still, while it is difficult to track his life at Miami, through the few records available of James T. Titus’s later life, his family and youth evidently influenced him in adulthood. For one, Titus, like his father, signed the “Memphis Secession Directory,” supporting Tennessee’s secession from the Union and joint of the Confederacy, before the Civil War officially began. Titus also enlisted to serve in the Confederate Army with the 1st Tennessee Volunteers. He served as a corporal in Company B, of the Tennessee 154th Infantry Senior Regiment, which was organized for the Civil War in May 1861.[29] With this regiment, Titus participated in “the difficult campaigns of the army from Murfreesboro to Atlanta.”[30] Upon the regiment’s return to Tennessee, James T. Titus was killed in the Battle of Nashville, at only 27 years of age. The death of James T. was one of the two that the Titus family suffered during the war.

Though Titus died at a young age, and few records of his lifetime are available, by looking into his family and ancestry, it is evident that the Titus family was a part of the elite class in the Southern United States that participated in the growing institution of slavery and the cotton industry that it provided, as well as American imperialism and relocation of Native Americans along the way. Thus, when James T. Titus came to Miami University, he fit the idea at the time that it was the sons of the elites who received a higher education. Titus and his family, with their connection to cotton industry, slavery, and imperialism, in addition to Miami, also represent and reflect the numerous other students that came to Miami in those early years, and their families, with similar connections to slavery and imperialism. Ultimately, James T. Titus is a case study to show how the university – like many others of its time – has a history that is deeply rooted and intertwined with the wealth of slavery, just as Craig Steven Wilder suggests.

Brittany Vonkamp is a senior majoring in History with a minor in Museums and Society.

Bibliography

1852, The Twenty-Seventh Annual Circular of Miami University, Comprising the Catalogue, The Course of Studies, etc., For the Year 1851-52, Cincinnati: T. Wrightson, in Miami University Catalog; Miami Catalog [Bound]; 1832-65, 8.

“Alderman nomination,” Frazier Titus Col, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, posted by wendyakeman, 23 July 2013, accessed 24 November 2018.

Ancestry person: James Titus, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, accessed 24 November 2018.

“Battle Unit Details: Confederate Tennessee Troops.” National Park Service. Accessed 9 December 2018. https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=CTN0154RIV.

“Biographical Information,” Ebenezer Titus, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, posted by wendyakeman, 7 April 2012, accessed 24 November 2018.

“Biography of James Titus Sr. by Ollie Lynn Titus,” James Titus, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, posted by wendyakeman, 2 April 2013, accessed 24 November 2018.

Early Tax Lists of Tennessee. Microfilm, 12 rolls. The Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, Tennessee. Accessed on Ancestry.com.

Early Tennessee/North Carolina Land Records, 1783–1927, Record Group 50, North Carolina (Revolutionary War) Land Grants, Roll 11: Book H-8. Division of Archives, Land Office, and Museum. Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, Tenn. Ebenezer Titus, Bell Family Tree, accessed on Ancestry.com.

“F Titus Presidential Pardon, pic 1,” Frazier Titus Col, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, posted by wendyakeman, 19 February 2012, accessed 24 November 2018.

“James Titus (1775-1843) Obituary info,” James Titus, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, shared by JenniferB Collins, 22 June 2016, accessed 24 November 2018.

Jones, James B. Jr. Hidden History of Civil War Tennessee. Arcadia Publishing, 2013. Accessed on Google Books.

Keating, J. McLeod. History of the city of Memphis and Shelby County, Tennessee: with illustrations and biographical sketches of some of its prominent citizens, Syracuse, N.Y.: D. Mason & Co., 1888. Accessed on https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=chi.20527175;view=1up;seq=502.

Miami University, 1809-2009: Bicentennial Perspectives. Edited by Curtis W. Ellison. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2009.

Mitchell, John L. Tennessee State Gazetteer and Business Directory for 1860-61, Issue 1. 1860. Accessed on Google Books.

“Moon, Titus & Co.,” Frazier Titus Col, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, posted by wendyakeman, 23 July 2013, accessed 24 November 2018.

Seventh Census of the United States, 1850; (National Archives Microfilm Publication M432, 1009 rolls); Records of the Bureau of the Census, Record Group 29; National Archives, Washington, D.C. Accessed on Ancestry.com.

Shakenbach Regele, Lindsay. “How Did Slavery Change Through the Early Republic?” Lecture, The Early American Republic, 1783-1815, Miami University, Oxford, Ohio, 29 October 2018.

“Soldier Details: Titus, James T.” National Park Service, accessed 7 December 2018, https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-soldiers-detail.htm?soldierId=668FC0D9-DC7A-DF11-BF36-B8AC6F5D926A.

“Tennessee Historical Magazine, Vol 3,” Ebenezer Titus, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, shared by BigMuddy2Sides, 11 August 2016, accessed 24 November 2018.

“Titus Block information,” Frazier Titus Col, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, shared by Frazor Edmondson, 15 April 2012, accessed 24 November 2018.

“Titus Block, Third & Market Streets, Memphis, Shelby County, TN.” Library of Congress. Accessed 26 November 2018. https://www.loc.gov/item/tn0139/.

Wilder, Craig Steven. Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2013.

“Will of James Titus,” James Titus, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, posted by wendyakeman, 1 April 2013, accessed 24 November 2018.

Young John Preston and A.R. James. Standard history of Memphis, Tennessee, from a study of the original sources. Knoxville, Tennessee: H. W. Crew, 1912. Accessed on https://archive.org/details/standardhistoryo00youn/page/116.

[1] Lindsay Shakenbach Regele, “How Did Slavery Change Through the Early Republic?” (lecture, The Early American Republic, 1783-1815, Miami University, Oxford, Ohio, 29 October 2018).

[2] “’Old Miami’ Themes,” in Miami University, 1809-2009: Bicentennial Perspectives, ed. Curtis W. Ellison (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2009), 10; “A New University in and Emerging Nation,” in Miami University, 19-20.

[3] Craig Steven Wilder, Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2013), 30.

[4] “Biographical Information,” Ebenezer Titus, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, posted by wendyakeman, 7 April 2012, accessed 24 November 2018.

[5] “Tennessee Historical Magazine, Vol 3,” Ebenezer Titus, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, shared by BigMuddy2Sides, 11 August 2016, accessed 24 November 2018.

[6] Early Tennessee/North Carolina Land Records, 1783–1927, Record Group 50, North Carolina (Revolutionary War) Land Grants, Roll 11: Book H-8. Division of Archives, Land Office, and Museum. Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, Tenn. Ebenezer Titus, Bell Family Tree, accessed on Ancestry.com.

[7] “Tennessee Historical Magazine, Vol 3,” Ebenezer Titus, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, shared by BigMuddy2Sides, 11 August 2016, accessed 24 November 2018.

[8] “Biographical Information,” Ebenezer Titus, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, posted by wendyakeman, 7 April 2012, accessed 24 November 2018.

[9] “Tennessee Historical Magazine, Vol 3,” Ebenezer Titus, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, shared by BigMuddy2Sides, 11 August 2016, accessed 24 November 2018.

[10] “Biography of James Titus Sr. by Ollie Lynn Titus,” James Titus, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, posted by wendyakeman, 2 April 2013, accessed 24 November 2018.

[11] Early Tax Lists of Tennessee. Microfilm, 12 rolls. The Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, Tennessee. Accessed on Ancestry.com.

[12] Wilder, Ebony and Ivy, 249.

[13] “Biography of James Titus Sr. by Ollie Lynn Titus,” James Titus, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, posted by wendyakeman, 2 April 2013, accessed 24 November 2018.

[14] Ibid.

[15] “James Titus (1775-1843) Obituary info,” James Titus, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, shared by JenniferB Collins, 22 June 2016, accessed 24 November 2018.

[16] “Will of James Titus,” James Titus, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, posted by wendyakeman, 1 April 2013, accessed 24 November 2018.

[17] “Alderman nomination,” Frazier Titus Col, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, posted by wendyakeman, 23 July 2013, accessed 24 November 2018.

[18] J. McLeod Keating, History of the City of Memphis and Shelby County, Tennessee: with illustrations and biographical sketches of some of its prominent citizens (Syracuse, N.Y.: D. Mason & Co., 1888), 484.

[19] John Preston Young and A.R. James, Standard history of Memphis, Tennessee, from a study of the original sources (Knoxville, Tennessee: H. W. Crew, 1912), 116-17.

[20] “F Titus Presidential Pardon, pic 1,” Frazier Titus Col, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, posted by wendyakeman, 19 February 2012, accessed 24 November 2018.

[21]“Titus Block information,” Frazier Titus Col, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, shared by Frazor Edmondson, 15 April 2012, accessed 24 November 2018.; “Titus Block, Third & Market Streets, Memphis, Shelby County, TN,” Library of Congress, accessed 26 November 2018, https://www.loc.gov/item/tn0139/.

[22] James B. Jones, Jr., Hidden History of Civil War Tennessee (Arcadia Publishing, 2013), [no page numbers provided].

[23] “Moon, Titus & Co.,” Frazier Titus Col, Bell Family Tree, on Ancestry.com, posted by wendyakeman, 23 July 2013, accessed 24 November 2018.

[24] John L. Mitchell, Tennessee State Gazetteer and Business Directory for 1860-61, Issue 1 (1860), 138.

[25] Wilder, Ebony and Ivy, 48.

[26] Ibid, 285.

[27] “Life at Old Miami,” in Miami University, 65.

[28] 1852, The Twenty-Seventh Annual Circular of Miami University, Comprising the Catalogue, The Course of Studies, etc., For the Year 1851-52, Cincinnati: T. Wrightson, in Miami University Catalog; Miami Catalog [Bound]; 1832-65, 8.

[29] “Soldier Details: Titus, James T.” National Park Service, accessed 7 December 2018, https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-soldiers-detail.htm?soldierId=668FC0D9-DC7A-DF11-BF36-B8AC6F5D926A.

[30] “Battle Unit Details: Confederate Tennessee Troops,” National Park Service, accessed 9 December 2018, https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-battle-units-detail.htm?battleUnitCode=CTN0154RIV.