Revolutionary Poetry

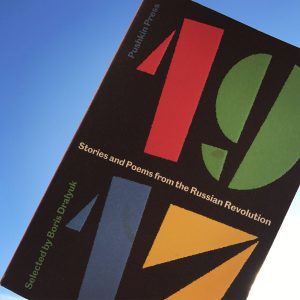

Note: Students in Dr. Stephen Norris’s Spring 2017 class, Introduction to Russian and Eurasian Studies, read Boris Dralyuk’s recent edited collection of poems from the 1917 Russian Revolution. For one assignments, several students wrote their own 1917 poems. Examples are below.

From the Inferno | Товарищ Иаков Бруггемана

By Jacob Bruggeman

The Worker stands,

Red flag in hand,

Atop the shell of old.

We stand, bold.

We scowl Westward;

No longer part

Of that sullen herd;

No longer an Anglo lark.

The German nation, too,

Obfuscates our truth in dark.

This is no longer true!

The truth, now, is stark:

Your days are few.

Time propels us,

History pumps our blood.

Proletarian posh lust

Erased by our flood.

The old now at dusk,

Our hour now in bud.

O forgotten fools:

Your Parisian bastards abound,

Enslaving souls as mules,

You must be uncrowned.

Beaten by workers’ tools,

O old world, now earthbound.

Let your retort be laconic,

Your laws have been drowned.

Ah, how beautifully ironic:

‘Now’ is your burial ground.

The laws of History cyclonic,

Judge without dissenting sound.

Hammered into Hell,

Limb to limb, feel the fire leap;

Of burning flesh, the smell swells.

You, doomed to damned sleep,

Married to perdition’s mademoiselle,

This is the fate you reap.

Satan rings your death knell,

Yet hope remains. In the thick

Smoke of inferno, you have an air well.

Join your slaves! This is no feudal trick.

Time is of the essence; you shan’t dwell.

Comrades, join our body politic!

This poem was inspired by Alexander Blok’s The Scythians. Blok’s poetry was guided by an eschatological vision of the world, through which Blok “fully expect[ed] the dreary, rationalistic, thoroughly corrupt world he had come to detest to be swept away by a destructive, “purifying” fire, which would then give rise to a new, harmonious way of life.”[1] The above poem has attempted—with hardly a simulacrum of poetic talent—to replicate Blok’s eschatologically-informed poetry. Much like The Scythians, From the Inferno espouses a vision of the end of the world in post-Revolution Russia. This poem, mirrored on Blok’s, presents a proletarian thrust into the future, one that would cast overboard—this analogy, used in other poems, meaning the ‘Ship of State’—old, bourgeois cultural artifacts. It makes sense, then, that Blok “had anticipated—indeed, had welcomed—[a] fire” that consumed his library.[2] Similarly, my poem espouses a militarized, even violent, pro-Bolshevik worldview. My poem is even structured in a way that aggrandizes the future, for as its narrative moves forward, the stanzas widen, signifying the growth of proletarian power. Furthermore, towards the end of the poem, wherein the petty bourgeoisie is extended a hand of comradeship, the proletarian body politic is represented as Messianic; an entity whose purpose is to lift the damned out of hell, and thus to preserve life.

[1] Dralyuk, Boris. 1917: Stories and Poems from the Russian Revolution. London: Pushkin, 2016. Print. Pg. 47.

[2] Ibid.

Вместе [Together]

By Erica Edwards

в

valiently we march through the land; through towns that lay

vacant. we carry the dream of a bolshevik

victory. we push on with the hope of crushing the bourgeoisie, in all their

vapidity.

м

мaybe we fight so fearlessly, because it is the only way to keep the doubt

мanageable. we believe in the cause, but does it justify all this

мurder? we struggle knowing we have been sponsors in the starving of children, are we all

мonsters?

е

yеsterday we speak of when we were young boys playing in the fields of wheat so

yеllow. we want the bolsheviks to keep their promises; but can they truly satisfy our

yе? we wish for the shelling to quiet; can lenin make voices of our dreams cease

yеlling?

с

stop, we say to the carnage! cease with the talking and

speeches! we ask; why don’t you bolsheviks halt with the lies and the

secrets? we try find an answer; did we agree to be your holders when we volunteered to be your

soldiers?

т

тoday we conspire no longer! we demand you let us return to our farms, our cities and

тowns! we stand still with the socialist ideals; but did anyone consent to this destruction and

тermoil? we reject this ugly despotism; lenin, why don’t you go back to germany with your ravenous

тerrorism?

е

еt, we dream these thoughts all alone in our beds.

еt, we scream these questions till there’s an ache in our heads.

et, we wish these sayings would fall on listening ears.

еt, we march these words into the ground, to be found by later years.

The Explanation:

In my interpretative piece I drew from primary sources found in Mark Steinberg’s Voices of Revolution and Boris Dralyuk’s 1917: Stories and Poems from the Russian Revolution. When I read both of these collections, particularly Steinberg’s, I was struck by how integral the idea of the collective was to the people of the lower classes. That is why in my poem I sought to expand on the idea of the collective, specifically through the lens of soldiers. I also felt that the feeling of betrayal in the writings following the beginning of the year 1918, was an important theme to incorporate into my poem. Synthesizing both of these nebulous ideas into one poem, to me, gives an accurate depiction of how the lower-classes felt as 1917 turned into 1918, and the Bolshevik approach to governance turned from quasi-democratic to outright authoritarian.

Before I dig into the significance of the stylistic decisions I made, and how they work toward building a theme that is shared in the Russian writing of 1917/1918, I would like to give an overview of the structure of my poem. Particularly, I wish to explain why my poem develops the way that it does. I intended the structure of this poem to mimic the historical chronology of the end of 1917 and the beginning of 1918. Specifically, the poem begins after the October Revolution and ends shortly after the violence and closure of the Constituent Assembly on January 5th.

The poem begins with letter “в [v];” here the soldiers are marching through Russia, they are thorough believers in the Bolshevik ideas and are supporters of the Bolshevik cause. While not everyone was supportive of the Bolshevik’s after they first gained full control of the government in October, people of the lower classes generally supported them as a step toward a democracy of all-socialist parties[1]. As the Bolsheviks begin instituting harsher restrictions on civil liberties, the soldiers began to express doubt in the efficacy of the Bolshevik party; eventually, their doubts culminate when one reaches the letter “с [s].” Here is when I intended the violence of January 5th to have occurred, and serves as the incident that changes the soldiers’ perspectives on the Bolshevik government.

Now that the structure has been expounded upon, I will begin my justification for the stylistic decisions I made, Overall, the theme I tried to express in the poem was that of the collective, and the conflicted thoughts and feelings of the average people that made up that collective. To me, soldiers represent a very tangible image of a collective; they are supposed to act as one and help one another reach a common goal. That is why I specifically focus on soldiers in my poem. This idea of a collective can be seen in the repeated use of the greeting “comrade” throughout the letters by soldiers in part one of Steinberg’s Voices[2]. And like the drum in Valentine Kataev’s short-story, there is a push-and-pull relationship between one soldier and the group to which that soldier is a part. This idea of “one as a part of many” is what inspired me to title my poem “вместе [vmeste, or “together”],” and then structure the poem with each letter being broken down into a stanza of its own. To continue the idea of a collective, I chose to include the repetition of “we” at the beginning of each sentence. Further, I wanted my poem to speak to the fact that each letter or poem in Steinberg’s Voices simultaneously represents the whole group of people (ie. peasants, soldiers, workers), but is also a declaration of that person’s particular belief.

So, while I did spend a lot of time thinking about the theme of the collective, I also focused on the idea of betrayal. After the Bolsheviks had been in power for a little while, and especially after they decided to close the Constituent Assembly, there was a feeling of deep betrayal among the lower-classes of society; this can generally be seen in the poems and writing in part three of Steinberg’s Voices, but because my poem focuses specifically on soldiers, I will only provide examples from the “Soldiers” subsection.

I feel that an excerpt from a letter written by a soldier to Lenin, dated January 6th, 1918, most accurately describes the sense of betrayal felt by those that had previously supported the Bolshevik cause: “You lie, scoundrel,…you promised loads, but did none of it. You are deceivers![4]” Another letter to Lenin from a soldier, this one dated January 15th, 1918, states, “Comrade Lenin, did you really seize power so that you could drag the war out for three more years? Comrade Lenin, where is your conscience, where are the words you promised…this is all lies.[5]” I wanted to embody that feeling of betrayal in the stanza succeeding “c.” I wanted to portray the same level of indignation that the soldiers felt (without the colorful language).

As a closing note, I would like to return to the title of this poem. I decided to have the title of the poem in Cyrillic letters because I thought it would be interesting to invert the style in which poems throughout this course have been read; specifically, the fact that we have mainly read poems, letters, and stories written in Russian that have then been translated into English. I also feel that keeping the title of the poem in Russian is a nod to the nationalism felt in the country immediately following the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II.

[1] Mark D. Steinberg, Voices of Revolution, 1917 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 258

[2] Ibid. 106-128

[3] Boris Dralyuk, 1917: Stories and Poems from the Russian Revolution (London: Pushkin Press, 2016), 94-108

[4] Steinberg, 292

[5] Ibid. 292

Seasons of Revolution

By Mohinee Mukherjee

Spring

Chill in the air and

Seeds are sown.

Among the sheep

A lamb—naïve and defiant—

Is born

And watches

As a storm brews in the sky.

Summer

Frequent monsoons yield

Emerald fields and

Bountiful crops—more than in years.

Sheep graze with glee.

Among the sheep

A lamb—naïve and defiant—

Learns to walk

Among pastures

So free.

Fall

Harvest comes and

Fields turn bare.

Sheep, unsure

Of where to go next,

Follow the shepherd

To unknown pastures.

Among the sheep

A lamb—naïve and defiant—

Frolics

Away from the drove.

Until,

It is herded back

Into the flock.

Winter

Blankets of snow

Cover the pastures.

Frost lingers

From every gust of wind.

Sheep can only trail

The shepherd, and

Willingly give their wool.

Among the sheep

A lamb—naïve and defiant—

Unwillingly

Follows the shepherd

To the sickle, and

Warm drops of red

Desecrate

The immaculate white.

As an allegory to the events transpiring in 1917 into early 1918, my poem follows the initial optimism of many of the Russian proletariat as the socialist revolutions gained fervor. In the end, however, it serves as a warning about blindly following the Bolsheviks until the party becomes totalitarian.

My poem is partially inspired by Mikhail Gerasimov’s Symbolist-style of writing, and attempts also to emulate the Proletkult feel with the pastoral backdrop. While Proletkult writers generally support the Bolsheviks and the proletariat class of factory workers and farmers, as they strive to transform the “‘tender’ pastoral world […] in their own steely, industrial image,” my poem stays true to traditional pastoral imagery and can be interpreted as anti-Bolshevik (Dralyuk 41).

Similarly, the sentiments of Marina Tsvetaeva are reflected in the poem, as she offers “a vivid portrait of the tumult unleashed by the February and October Revolutions […]” (Dralyuk 18). For the poem written during the last days of October 1917, Tsvetaeva initially shows the excitement of people as the revolution unfolds, as she says, “The world and its wine—ours! The town stamps about like a bull, swills from the turbid puddles” (Dralyuk 20). Then, she suddenly ends the poem with “Deep in wine—a couple has drowned” (Dralyuk 20). While Tsvetaeva is more frank about her disagreement with the revolutions and the aftermath in her poetry, I strive for more subtlety with pastoral symbols. However, like Tsvetaeva, I attempt to show a positive image of the revolution and finish the poem with an unanticipated conclusion.

In one year, 1917, many different political entities vied for control of Russia, which ultimately led to the Bolshevik’s seizing power. For that reason, I divide the poems’ stanzas into seasons to reflect the time periods in which each period has a new party become more prominent. Moreover, the sheep, a common symbol for something that follows an idea or person blindly, represents the proletariat who follow Bolshevik ideas without question. The lamb represents the Russians who are bystanders when the Bolsheviks fight for power against other parties, and who nonetheless face the consequences of a Bolshevik government. The shepherd is the Bolshevik party, which grows in influence over the Russian people.

In Spring, the “Chill in the air” and “storm brew[ing] in the sky” represent the tension that results when the power dynamic shifts from the imperial system to the socialist entities.

In Summer, the “Emerald fields and / Bountiful crops” resulting from the “Frequent monsoons” represent the growing power of the socialists and the rising influence of the Bolsheviks, which provides an opportunity for the peasants to seize land from the bourgeoisie (“Sheep graze with glee”). Even the bystanders benefit from the redistribution of land (“Learns to walk / Among pastures / So free”).

In Fall, the excitement of the revolution declines as the fighting between the Bolsheviks and the other socialist group increases (“Harvest comes and / Fields turn bare”). Eventually, the Bolsheviks seize power in the Second Congress of the Soviets with the October Revolution, and they create the Sovnarkom. This creates a new era in Russia, and the future of Russians is uncertain. Nonetheless, many Russians obey the Bolshevik decrees (“Follow the shepherd / To unknown pastures”), and those who initially do not must comply or face consequences (“Until, / It is herded back / Into the flock”).

In Winter, as the Bolsheviks establish more authoritarian rule with writing more decrees, creating the Cheka, and dismantling law courts and the Constituent Assembly, the political efficacy of the Russian people diminishes (“can only trail / The shepherd, and / willingly give their wool”). Moreover, punishments for anti-Bolshevik actions are severe, as many disappear or are killed (“To the sickle”). The growing political power of the Bolsheviks over dissenting groups becomes more evident with time (“Warm drops of red / Desecrate / The immaculate white”).

This poem takes an element of the pastoral Symbolist-style of writing from Mikhail Gerasimov and the discontent of the Bolsheviks from Marina Tsvetaeva to provide a warning that a Bolshevik government will result in more harm for the Russian people.

In the year 1917, when revolutionary feelings in the then Russian Empire reached a boiling point and the Tsarist empire collapsed, numerous writings were produced by a wide variety of Russian peoples. They included hardworking peasants that desired the freedom to possess their own land to soldiers wishing to discontinue fighting in a baseless, territory-driven war to essentially anyone with a proclivity toward anti-Bourgeoisie sentiments. The two poems that follow are similar to what one might encounter in “The Voices of Revolution” and “Stories and Poems from the Russian Revolution,” compiled by Mark D. Steinberg, and Boris Dralyuk, respectively. However, what has been assembled here has never been viewed by anyone other than myself and those who had authored them; they are the dregs of the faintest of echoes of the collective outcry of the Russian peoples at a time when revolution seemed to be the only means by which they would be delivered to better lives and a United Russia.

Poems of Revolution

By Tyler Sagendorf

Why We Marched

Olga Andreevna

Baseless coward and treasonous leader,

You barricade yourself in that palace.

While Russia starves and you cannot feed her;

Your words are lies, promise conceals malice.

We stand here now, hoping, begging for change,

The bread is gone, “rationed”; the shops lie bare.

Sovereign unable to provide, how strange,

A crumb, a fragment, nothing you will spare.

You turn your ears away, our cries reach not,

The soldiers came, ordered, to disband us,

We beg, implored, please join; our deaths they sought.

They fired volleys, lives extinguished thus.

Bodies, broken, in Petrograd they lie.

In time, the people will be asking why.

Why we marched.

“Why We Marched” is a Shakespearean sonnet – 14 lines with an ABAB rhyme scheme ending with a couplet – written by Olga Andreevna, one of the female textile workers who, “took to the streets of Petrograd” to protest dwindling bread supplies (Smith, p. 5). She blames the Tsar, Nicholas II, for his ineffectual leadership as being the cause of many people being unable to feed their families and hates the soldiers for blindly following orders and causing unnecessary casualties. Ostracized because of her love of English and, therefore, capitalist poetry, Olga Andreevna never submitted her work for publication. Her poems and stories were written in solitary, relegated to a makeshift wooden box buried some five meters away from her place of dwelling. That is, until it was unearthed some years ago during the construction of a modern apartment complex. The argument in this piece is that the Tsar is unable to feed his subjects and the rationale behind that is the stores are devoid of the barest necessities such as bread and some people are facing starvation.

Abdicated the throne! Abdicate the throne!

Baird Muirland

Abdicated the throne! Abdicate the throne!

Y’ feast on the corse of Russia, sucking the marrow from ‘er bones!

Ye vacuous coward cavorting with sorcerers and demons!

You’re not fit to rule us; ya shall be punished for your treasons!

Hang ‘em, shoot ‘em, slice off ‘es head!

The whole of Russia will rest easy once ye are dead!

And as for the fate of yer son, the weak little heir?

His death will come swift. We are merciful, we are fair.

As for your wife, the tsarina? We heard what goes on.

She and that “monk” Rasputin will also be drawn

Up by their necks with a thick cord of rope!

I do not think that will kill him, at least, of that I hope!

We’ll stab him and shoot him and then drown him in icy water!

He’ll bloat like a pig and we’ll revel in the slaughter!

From the rotting flesh of these dictators and monsters

Shall sprout the seeds of a new government controlled by the people, and all the much stronger!

Rejoice! Rejoice! For the Tsar’s abdication

Will momentously benefit the next generation!

This poem, left untitled with an AA/BB/CC rhyme scheme and heavy usage of exclamation points, was found hastily scrawled on the back of a poster depicting the “greatness” of the Tsar, Nicholas II, and signed by a Scot of the name Baird Muirland that had become embroiled in the political and social tumult of Russia due to familial ties shortly before the Tsar had abdicated the throne. While the language and vehement demands may be a little harsh to some, it pales in comparison to some already-published works, however violent they may appear.

Furthermore, one must look at this through the lens of 1917 when tensions are high and, to many, the Tsar is the only thing standing between them and a utopian Russia. In their eyes, and true to history, he was an irreverent ruler who was not versed in methods of proper leadership and his actions caused many casualties during the Great War due to his insatiable need for amassing huge tracts of land in order to expand his already unstable empire.

The aforementioned information about this man was discovered by cross-referencing his name with records in Scotland. However, what happened after he composed his “Abdicate the throne! Abdicate the throne!” is a mystery, though there are no records of him ever returning to Scotland. One can assume he met a gruesome fate once the writing was discovered and passed on to officials in the Tsarist regime.

Another interesting thing to note is the fact that this man seemingly predicted how Grigori Rasputin would ultimately die. Perhaps it is a coincidence? Perhaps someone read it and thought it was a good idea? We may never know for sure, but the idea is interesting to puzzle over nonetheless.

Ode to the Proletariat

Anonymous

Honorable Proletariat!

What is better than to work for your daily bread!

To sweat and toil and earn everything you have in life!

Much better are you than the Bourgeois –

Those, like babes with supple skin and no talent for crafts,

Having weak constitutions unfit for labor.

Come, honorable proletariat!

Seize your place in the sun, bask in its radiance, for you deserve nothing less.

Noble proletariat, you who bear the weight of Russia on your back,

Like Atlas holding up the sky,

So that others may be allowed the freedom to have privileged lives.

We are indebted to you.

This last poem, an ode – a celebratory poem that utilizes literary devices such as simile and metaphor to make comparisons to a loved person or thing – was written by an anonymous Russian citizen with an apparent deep love for the proletariats. In it, he commends the proletariat for being the one to hold up the entirety of Russian society, like Atlas holding up the sky, and toiling away so that the “higher-ups,” the aristocrats and church members, can afford to have their luxuries in life.

The overarching theme in the first two poems is the ineffectual leadership of Nicholas II and how that causes issues, such as with the bread shortage and how he dealt with it, or how he is treasonous for having dealings with the monk Rasputin. The final poem simply demonstrated the theme of the exoneration of the proletariat, which was the basis for many Bolshevik political stances during the early months of what quickly became the revolution.

CONSISTENCE OF HOPE

By Aleah Sexton

The chaos of 1917 – from the initial revolution on February 23rd when female textile workers stormed the streets of Petrograd (now St. Petersburg again) until December, when Bolshevik forces fatigued the nation with decrees – was captured through the impulsive and hopeful nature of poet Katerina Volkova. Her revolutionary enthusiasm is evident through an ability to document the occurrences with a poetic lens. Russia of 1917 was plagued with a multi-vocal struggle of power from the spheres of influence regarding class, government, and identity. The foundation of the revolution bred an unprecedented nationalism among the proletariat that was irrepressible. The unvoiced suddenly gained a responsibility to express their grievances and visions. As stated by Fyodor Korsun, a private in the infantry in March 1917 and recorded in Mark D. Steinberg’s Voices of Revolution, 1917: “For the people, Hurrah! No longer shall our blood be drained by tsar above. Freedom is ours now” (81). Korsun’s excitement for the revolution and end to the reign of Nicholas II was supported by thousands of Russia’s underprivileged – including Katerina. Her historic presence begins as a regular textile worker at the Putilov Mill in Petrograd. Her diary was found in an abandoned apartment in 1951 and her political poetry was chronicled as a valuable primary source of a women’s take on the 1917 events. Wed to a soldier and mother to two-year-old Anatoly, she dreamt of a united Russia with equal rights for genders and opportunities for the neglected. Her utopian socialistic outlook led her to explore the teachings of Vladimir Lenin and eventually believe his propagandist narratives. Katerina continued to trust the Bolshevik’s policies until the end, although her frustration with their system of governmental legislation is expressed in many of her poems from late 1917 throughout 1918. Volkova’s husband enlisted under the Red Army and was under close command of Leon Trotsky. Eventually, it is believed he was recruited to the Cheka. Katerina continued her work at Putilov Mill throughout the Bolshevik reign and held several chair positions on socialistic industrial committees for women. Katerina Volkova passed away in 1936 due to complications with lung disease. Her dedication to the revolutionary movement is unforgotten. Her ability to capture the radical events through various emotions is crucial to unearthing the chaotic nature of 1917.

KATERINA VOLKOVA (1891 – 1936)

The Day

The shoes we made battered the streets

for all of Petrograd to hear.

-Disgrace! – shouted those with

bread in their pockets and bosoms so

full and endeared.

For we: the nameless, the breathless,

the dreadful and crooked stormed

for our children and guardians

and warriors unspoken.

Starved and defeated

we had our comforts.

My god we wondered.

Will we be triumphant?

Fingertips colored.

Deep hues of violet and light

shades of yellow dripped across

from the dye.

Our hands held up: we lit the

blank sky.

We did this for more.

More than bread – more than war.

Freedom.

A hum so mute and ignored –

yet somehow – someway – it played

a sweet chord…

3 March, 1917

KATERINA VOLKOVA (1891-1936)

Imminence

Here they come.

Quick!

Hide your books.

Hide your poetry.

Hide your manifestos.

Pretend to be the people

we were.

A year ago – a century ago.

Back to our days of chains

and commands.

Cover your personas with

the blanket of ignorance.

Maybe then – they will

let us be once again?

NO! Shrieked

us following the

likes of Bolsheviks.

FIGHT! Cried the

New Petrograd.

DO NOT DESPAIR!

For we are the future.

You will flock to us

like vultures on

fresh meat.

Let our dreams

build a new

Russian oasis.

The children of

your children will

be taught about US and

OUR FORTHCOMINGS.

22 AUGUST, 1917

KATERINA VOLKOVA (1891 – 1936)

The Prospect of Warranted Decrees

Every morn I awake with

hope that the paperboy

with the crooked hat will

shout – Decree! – without

the pain in his voice.

For once, just once! –

may his accent reveal

the news we all

have pledged for.

Peace! Land! Bread!

Alas – but where?

We spread their promise!

Naïve? Not we!

We pledged our allegiance!

The blood of Russia will

seep the memorandum!

Red! Red! Red! Red!

Damn those deserters!

Our new land will

trample upon their

gardens of doubt.

Abandonment is

beyond the time.

Move forward – we must.

Bolsheviks: please deliver

us what we have placed in

your trust.

2 DECEMBER, 1917

The goal of this paper was to reveal the numerous emotions a common woman would express throughout the relentless challenges and transformations of 1917 Russia. I decided to build the character Katerina Volkova through three poems to show the reader how Katerina’s own visions, hopes, and frustrations are highlighted. She begins with a poem about the Women’s March on Petrograd. Her anxiety is apparent, but she embodies a tone of excitement and a foreshadowing of something great. Her optimism could be compared to Vladimir Kirillov’s in his poem “We”, “We’ve cast off the oppressive burden of tradition / rejected the chimeras of its bloodless wisdom. / Venus de Milo cannot match the vision / of young girls in our Future’s shining kingdom” (Dralyuk 43). Kirillov writes of a nontraditional Russia with a future of utopianism, much like how Katerina wrote about freedom and also defying the tradition forced upon the underprivileged.

However, the exhilaration after the February Revolution was not personified within every Russian. Alexander Kerensky and the Provisional Government immediately built an institution of hidden bourgeoisie interests of the old conventionalism, and worker A. Zemskov wrote on the obviousness of this. Zemskov goes into detail about this infectious liberty most of Russia is accepting, however, he questions the Provisional Government’s stance: “The whole question, though, is whether it’s freedom’s praises you are signing. Aren’t you singing the praises of new chains that are only going by the name of freedom? (Steinberg 87). This fear of bourgeoisie interests is undermined in Katerina’s second poem, as well. She begins with stanzas that speak of retreating to the command of the Provisional Government but then changes the tone to express a steadfastness for the Bolshevik movement.

The Bolsheviks offered a newness to the revolution that sparked interest among the workers and soldiers. As written by two soldiers, “we need the program of your Bolshevik party like a fish needs water or a man air” (Steinberg 68). The Majority offered 1917 a vision without bourgeoisie intent, but of total socialism. Once the Bolsheviks did officially seize power in October, their supporters were ready for Vladimir Lenin to deliver his promises. Conversely, that was not the case. Zinaida Gippius in her poem “Now” highlights the letdown of the Bolsheviks on November 9th: “Our guardians and warriors / have all retreated. / There’s no one but conformists / with their Committees” (Dralyuk 21). The Bolsheviks newfound power instigated a chaotic need to install a dictatorship. Committees wrote hundreds of decrees to instill their hold on Russia, but the peasants felt their voice had been forgotten. In Katerina’s final poem, she focuses on the anxiety the Bolsheviks have caused and pleads for them to deliver what they promised. Workers in the Putilov factory voiced their discontent with the Soviets in December, stating that “you have earned yourselves enemies in the person of the workers by being more concerned about the bourgeoisies than about the lower class of workers and peasants. For the second month, workers have failed to receive their pound of sugar” (Steinberg 275). The working class expected an immediate resolution from the Bolshevik party. When this was not the case, many became angry and considered the new government another one with interests for the bourgeoisie.

Russia in 1917 was a frenzied nation with a demand to rid the old and establish a modern institution built on the voices of those that remained silent for so long. Poetry was an effective means to deliver the revolutionary spirit as quickly and efficiently as possible. Readers can distinguish the raw confusion, excitement, anger, and distrust that most of the workers and peasants expressed. Though many documents and poetry capture differing opinions on Russia’s governmental needs, most agreed that a change was vital for a united Russia.