RUSSIA’S REVOLUTIONARY SOURCES. PART III: POEMS. “Indecision and Interpretation A visual analysis of Alexander Blok’s The Twelve”

By Emily Oneschuk

The following documents were the basis for this paper and can be found in the De Saint Rat collection of the Havighurst Special Collections Library.

Blok , Aleksandr Aleksandrovich. Dvenadtsat’.: Berlin: Neva, 1922.

Blok, Aleksandr Aleksandrovich. Dvenadsat’. Skify. Paris, 1920.

Masyutin, Vasily. Critique of Dvenadsat. Miscellaneous essay. Berlin, Feb 1922.

In his poem, The Twelve, Alexander Blok captures the squalor and darkness that followed the arrival of Bolshevism in 1917. The “morning after revolution,” to employ a term used by Anne O’Donnell, that Blok depicts was a time after the Bolshevik seizure of power that was characterized by chaos, disillusionment, and confusion. Blok was a member of the intelligentsia, which put him in the unique position of being a separate entity from both the common people and the new ruling party. The publishing of The Twelve forced Blok to be viewed as even more of an outsider; Blok’s literary peers and friends viewed the poem as a pro-Bolshevik work because it did not explicitly denounce the revolution. Despite the sentiments of Blok’s peers, the Bolsheviks took note of the religious undertones of the work and denounced the author because they felt he was promoting the old ways.

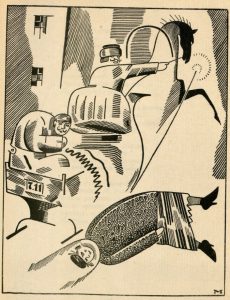

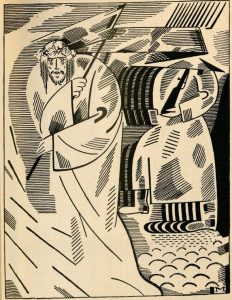

The poem thus proved quite contentious after its publication:some of the most interesting analysis of the work can be seen in its illustrations. The Twelve was illustrated numerous times in several countries, each depiction revealing a new way of looking at Blok’s work. Two of the most intriguing Russian illustrators included Vasily Masyutin and Yurii Annenkov, whose works are included on the cover page. Masyutin illustrated the poem in 1922 while living in Berlin, working independently of the author. Unlike Masyutin, Blok personally commissioned Annenkov to illustrate a version in August 1918, seven months after the poem’s initial publication. Blok heavily influenced Annenkov’s illustrations, and Annenkov’s memoirs help to detail exactly what the author wanted his poem to say (which at times is not very clear, even to Blok himself). While Masyutin’s and Annenkov’s illustrations follow the same monochromatic and serious theme, each illustrator was able to convey a very different sentiment by selecting which scenes and characters to depict.

The most popularly illustrated scenes in the poem are Kat’ka the prostitute’s death and Jesus’s appearance at the end of the poem, which not coincidentally are the scenes that Blok discussed most with Annenkov. By looking at Annenkov’s memoirs and his correspondence with Blok, it is evident that Blok had no strong political or religious intentions for his poem. Blok intended to describe the world around him and any political or religious sentiments were seemingly coincidental. Even the appearance of Christ at the end of the poem was not something he intended; in a discussion with Annenkov he lamented that he did not want to place Christ there, he only did so because could not think of something to replace him. Annenkov’s view of the poem is similar to that of Blok’s. He did not find the poem to be especially prophetic, and saw the religious illusions to be portrayals of communist leaders, not a revival of a forgotten Holy Russia.

Masyutin, on the other hand, was obsessed with the religious imagery in The Twelve. He illustrated it for a version published in Berlin and wrote a passionate critique of the poem. In it, he described the poem as monochromatic, with a “bloody red stain of spilled blood.” Masyutin sees the poem as being an almost religious description of the events of the revolution. To Masyutin, the twelve soldiers in the poem are reminiscent of the twelve apostles, and their march is congruent with the inevitable progression of fate and time. He put a lot of emphasis on Jesus’s role at the head of the procession, a role that he ascribed to the inevitability of salvation. In his final image, Christ is a calm, imposing figure at the front of the military procession, proudly holding the flag of his nation and leading his people to a newfound salvation.

Blok did not share Masyutin’s idea of Christ’s role in the poem. He was indecisive regarding the topic and had so much trouble deciding how Christ should be portrayed that Annenkov eventually refused to illustrate him. At first, Blok wanted Christ portrayed as a large figure next to a flag, then as a minor figure next to the troops, and at one point wanted him in Kat’ka’s picture, which he wanted to use for the cover of the book. Annenkov recognized that no matter how he portrayed him, Blok would be unsatisfied and in the end, he refused to illustrate Christ alltogether. The final illustration in Annenkov’s collection does not include Christ, but instead focuses on the march of the soldiers into the night and emphasizes the vast and empty spaces that they are patrolling.

Blok simultaneously loved and disapproved of Annenkov’s illustrations. Through the course of their correspondence, he changed his opinion on the image of Kat’ka and Christ numerous times. At first, he raved about the image of Kat’ka, saying she should be blown up to full poster size and that the book should be printed larger to accommodate the grand scale that this image required. Then he decided he did not like the model and that a healthier, plumper Russian girl was needed. She was supposed to be a vibrant, cheerful girl and Annenkov had portrayed her in an overly cynical, realistic manner. The resulting picture is striking and very emotional; Ka’tka is dramatically sprawled on the ground, while her lover Petruhka looks on, distraught and heartbroken. Masytin does not focus on Kat’ka at all in his illustration, but instead puts emphasis on the soldiers leaving the scene and moving on through the city. There is a lack of feeling in Masyutin’s imagine; Petruhka appears to look only mildly shocked at the death of his lover and there is nothing remarkable about the dead girl strewn about on the street. Again, Masyutin’s focus here is mainly religious and very different to that of Blok and Annenkov. The march of the twelve (and thus, the progression of life and salvation) continues on, regardless of what terrible tragedies befall mankind.

The focuses of these two artists are based on very different interpretations of Blok’s writing: one guided by the author himself, and the other, a passionate manifestation, totally unaligned with what the author intended. As demonstrated by Masyutin’s interpretation, Blok’s vision was very different from what his peers and rivals ascribed from the poem. His work can be seen as a parallel to the revolution; its intentions not fully understood by its creators or its audience, and its effects unpredictable, controversial and contradicting.

Works Cited

Annenkov, Yurii, George Waldemar, Aleksis Rannit, and Evgeniĭ I. Zami︠a︡tin. Dnevnik Moikh Vstrech: T︠s︡ikl Tragediĭ. New York: Mezhdunarodnoe literaturnoe sodruzhestvo, 1966. Print.

Emily Oneschuk is a senior Mechanical Engineering and REEES major.