RUSSIA’S REVOLUTIONARY SOURCES. PART II: PHOTOGRAPHS AND NARRATIVES. “An Album of Revolution, Part I.”

By Courtney Misich

DK265.15 .T46

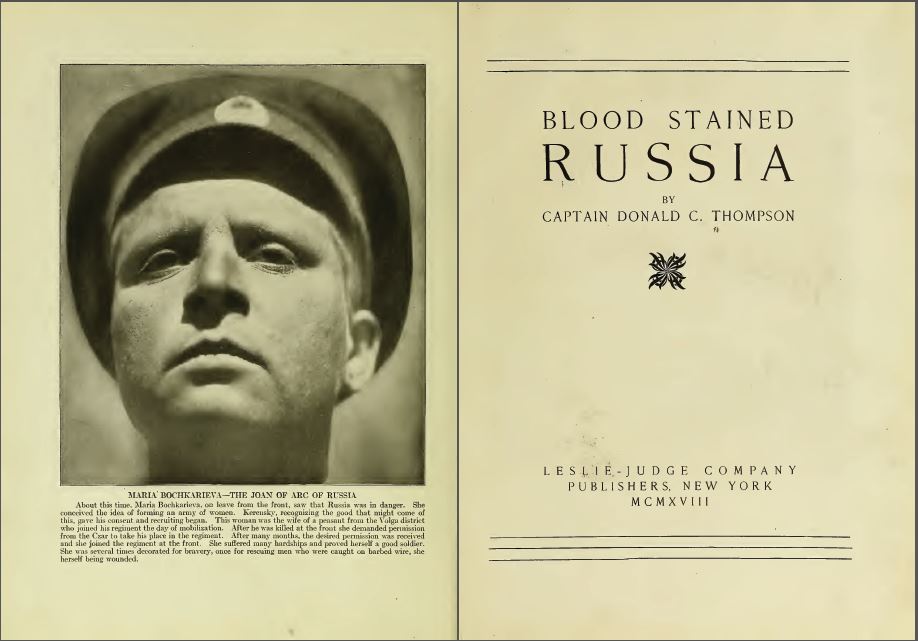

Thompson, Donald C. Blood Stained Russia. New York : Leslie-Judge Co., 1918.

This medium-sized, red book, Blood stained Russia, offers insight into the American views of the Russian Empire, war effort, and subsequent Russian Revolution. Donald Thompson and Florence MacLeod Harper were in Petrograd (St. Petersburg) during the February Revolution when Thompson decided to record the revolution. MacLeod described the process and published work in the following way: “no important scene in the great Russian drama from the time of the overthrow of the Czar and the brief triumph of the unhappy Russian people, down through the various stages of their undoing by the malignant forces in Berlin until the final overthrow of the Provisional Government, that Captain Thompson did not see and record.”[1] These photographs and their captions describe the Western, specifically American, perspective of the Russian Revolution through the descriptions of the sides and causes of the revolution.

In order to understand this source, the photographer and author Donald C. Thompson‘s purposes for being in Russia need to be clarified. David Mould’s biography depicts Thompson as a war photographer that relished in the danger and adventure.[2] Thompson had several encounters with the law; first for impersonation of army personnel and eight times during the First World War front for not having official permission to be there. Once at the front, he stayed in the trenches with the soldiers. Thompson’s pictures captured the war, specifically the Western front, for the American public. He toured the front with the Belgian army and interacted with the German military on a frequent basis. When Thompson went to the Eastern front, he believed “the Russian army, which had been mobilizing for six months, could change the course of the war.”[3] He provided footage for films on the Eastern front with the Tsar reviewing the troops and Russian troops fighting. In January 1917, he went to Russia with Florence Harper through China and the Trans-Siberian railroad. They stayed in Petrograd with trips to Moscow and the front lines filming everything that preceded the October Revolution. The images were originally released as a film titled The German Curse in Russia, which was released December 1917.[4] Thompson’s views of Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky are clear to readers in the film and this work through the captions he provides.

Thompson frames the work with periodized themes such as “Before the Revolution” and “Hospital Conditions at the Front,” which appear simple until one examines the photograph titles. The pictures portray the Bolsheviks being supported by the Germans, loyal Russians being led astray, and the aftermath of war and revolution in Russia. It is important to note, as Joshua Sanborn has written, that “this antagonism [towards Germans] had been present in central Russia and elsewhere in the empire before the war.…an increasing number of people were growing exponentially angrier and more hostile toward the German element in their midst”[5] Before the February Revolution, it was widely believed that the Russian Army’s military inadequacies in part stemmed from German propaganda and spies that had infiltrated the Russian government. Thompson described “when supplies were kept back by pro-German agents in Petrograd headed by the Minister of War, Soukhomlinoff,”[6] as the one of the main causes of the problems in Russia that led to the revolution as well as the betrayal of the Tsar. The betrayal by the Tsar is represented by a picture of Rasputin, which described him as “the evil genius of the old regime.”[7] Thompson depicts these outside influences within the Russian government and military as the causes of the revolution.

Figure 1 the Monk Rasputin, the Evil Genius of the Old Regime in Russia, Surrounded by Admiring Women[8]

Bloodstained Russia focuses on the February Revolution until the October Revolution with a continued focus on the Germans as the perpetrators of the Provisional Government’s failing. The view of Germany’s baleful influence in Russia is a constant presence throughout the book and demonstrates the American perspective that the German government was funding revolutions in other countries to win the war. An image in the “Parades and Labor Riots of May” shows the protest that occurred in support of the war. It is captioned, “As time went on, however they became disheartened. German propaganda insidiously demoralized them and parades like this became fewer and fewer.”[9] The perspective of the power of the German propaganda even went initially as far as the Bolsheviks. Significantly, Thompson utilizes the term “German” to include the Bolsheviks and only separates them when he is forced to. Sanborn has also described the connections between the Bolsheviks and Germans in the popular mind. He writes “Bolshevik ties to Germany nearly undid them…The Bolsheviks had willingly taken huge payments from a Germany government that had come to see revolution as a far more feasible option for knocking Russia out of the war.”[10] This lack of distinction altered once it became clear to Thompson that the Bolsheviks were challenging the Provisional Government.

Figure 2 A Parade in Advocacy of a Vigorous Offensive against Germany[11]

Furthermore, the connections between the Bolsheviks and the Germans are clear with Thompson’s photo titled “Here are seen some of the banners which Lenin had had made in Germany.”[12] The representation of the Bolsheviks as connected to Germany is one characterized in respect to their perceived disregard for human life and as agents of chaos. Thompson described their methods as a campaign of terror where they attempted to seize the government, shooting up the town with machine guns, and anarchistic. As the revolution continued, Thompson recorded the changing attitudes at the front with soldiers believing that their German comrades would not harm them. The changing perspective was best summarized with a statement from one of the soldier’s at the front, “the Germans were their brothers and would no longer kill them.”[13] This changed view stems from increased interaction at the front, as soldiers such as F. Zakharin described.[14] This view was quickly dismissed with images of Russian soldier who had died in German gas attacks and the continued fighting at the front.

After focusing on what Thompson labels “front stuff,” the album turns to the October Revolution, with its “Bolsheviki riots, armoured cars, and crowds.” The American war photographer displays his support for the Provisional Government and Kerensky. His portrayal of Kerensky is the opposite of the Bolsheviks: photos capture him actively trying to work for the Russian people, running the war, and honoring Russia’s fallen men. Thompson shows Kerensky arming workers and utilizing the Soviets to defend Petrograd from “General Korniloff.” However the so-called Kornilov [Korniloff] Affair is not depicted visually, and the album suddenly turns toward the Bolsheviks in power. By the end, Thompson calls the Bolsheviks “anarchists controlling the Russian government.”

Bloodstained Russia provides an American perspective of Russia in the First World War and revolution. The work captures an anti-German mindset held by Americans and some Russians. At the same time, Thompson’s album contains more than just anti-German attitudes. For those who are interested the Women’s Battalion of Death, Thompson’s work contains nearly thirty photos of the unit, their training, and leader, Maria Bochkarieva. Additionally there is significant representation of front hospitals, medical care, and the impact on society from the war with orphans and shortages.

In many ways, Blood Stained Russia attempts to counter more positive accounts of 1917 promoted in such pro-Bolshevik albums such as the Album of Revolutionary Russia. This book, as Riley Kane argues in his paper, tells a different story using photographs taken as the same time as Thompson’s.[15] Just as the meanings of 1917 were fought over on battlefields, so to were they contested in print.

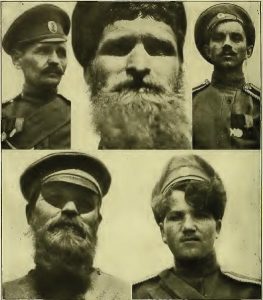

Figure 3 Types of Russian Soldiers[16]

Bibliography

“New Russian War Film.: Donald Thompson’s Pictures Show Regiment of Women in Training,” in New York Times December 10, 1917.

Album of Revolutionary Russia. [New York] : Russian Socialist Federation, [1919].

Daly, Jonathan W. and Leonid Trofimov, Russia in War and Revolution, 1914-1922: A Documentary History. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub., 2009.

Mould, David Harley. Donald Thompson: Photographer at War. Kansas State Historical Society, 1982.

Sanborn, Joshua. Imperial Apocalypse: The Great War and the Destruction of the Russian Empire. Oxford, 2014.

Thompson, Donald C. Blood stained Russia. New York : Leslie-Judge Co., 1918.

Thompson, Donald C. Donald Thompson in Russia. New York: Century, 1918.

Thompson, Donald C. Fighting the war. Los Angeles: Flicker Alley, 1916.

Suggested Readings

Billington, James H. “Six Views of the Russian Revolution.” World Politics 18, no. 3 (1966): 452-73. doi:10.2307/2009765.

Castellan, James W., Ron van Dopperen, and Cooper C. Graham, eds. American Cinematographers in the Great War, 1914-1918. Indiana University Press, 2015.

Dopperen, Ron Van. “First World War on Film.” First World War on Film. 1970. Accessed December 14, 2016. http://shootingthegreatwar.blogspot.com/.

Goldenweiser, Nicholas. “Antecedents of the Russian Revolution.” The American Political Science Review 11, no. 2 (1917): 383-85. doi:10.2307/1944013.

Lieven, D. C. B. The end of tsarist Russia : the march to World War I and revolution. n.p.: New York, New York : Viking, 2015.

PBS Online. “American Photography: A Century of Images.” Photography and War.

Poe, Marshall. A People Born to Slavery: Russia in Early Modern European Ethnography, 1476-1748. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000.

Ray-Dye, Chelsea. “Within the Looking Glass: How a War Photographer Became a Hero during World War I.” IUSB Undergraduate Research Journal of History 5 (2015): 185.

Stewart, H. L. “Some Repercussions of the Russian Revolution.” International Journal 1, no. 3 (1946): 218-28. doi:10.2307/40194082.

Von Mohrenschildt, Dimitri. “The Early American Observers of the Russian Revolution, 1917-1921.” The Russian Review 3, no. 1 (1943): 64-74. doi:10.2307/125233.

Von Mohrenschildt, Dimitri. “The Early American Observers of the Russian Revolution, 1917-1921.” The Russian Review 3, no. 1 (1943): 64-74. doi:10.2307/125233.

Zimmerman, William. “The American View of Russia.” The Wilson Quarterly (1976-) 1, no. 2 (1977): 118-28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40255188.

[1] Donald C. Thompson, Blood stained Russia, ( New York : Leslie-Judge Co., 1918) v.

[2] David Harley Mould, Donald Thompson: Photographer at War, (Kansas State Historical Society, 1982), 154.

[3] Mould, Donald Thompson, 163.

[4] “New Russian War Film.: Donald Thompson’s Pictures Show Regiment of Women in Training,” in New York Times (December 10, 1917), 15.

[5] Joshua Sanborn, Imperial Apocalypse: The Great War and the Destruction of the Russian Empire (Oxford, 2014), 95.

[6] Thompson, Blood stained Russia,10

[7] Thompson, Blood stained Russia, 19.

[8] Thompson, Blood stained Russia, 19. “The Monk Rasputin, the Evil Genius of the Old Regime in Russia, Surrounded by Admiring Women”

[9] Thompson, Blood stained Russia, 44.

[10] Sanborn, Imperial Apocalypse, 224-225.

[11] Thompson, Blood stained Russia, 44. “A Parade in Advocacy of a Vigorous Offensive against Germany”

[12] Thompson, Blood stained Russia, 136.

[13] Thompson, Blood stained Russia, 164.

[14] Jonathan W. Daly and Leonid Trofimov, Russia in War and Revolution, 1914-1922: A Documentary History (Indianapolis: Hackett Pub., 2009), 86-87.

[15] Album of Revolutionary Russia. [New York] : Russian Socialist Federation, [1919].

[16] Thompson, Blood stained Russia,200. “Types of Russian Soldiers”

Courtney Misich is a second-year MA student in History.