Displayed among a group of ancient artifacts in the Global Perspectives Gallery at the Richard and Carole Cocks Art Museum (RCCAM), Miami University, is part of a carved column from ancient Egypt measuring just over 16 inches in height. The relief fragments make up a partial scene depicting the pharaoh Amenhotep IV, later known as Akhenaten (reigned c. 1353-1334 BCE), making a sacred offering.

The fragments were donated to the Art Museum by founder-donor and “Monuments Man” Walter I. Farmer in 1978, yet there’s a problem: there is no documentation in our files about how, where, and when Walter Farmer acquired them. Through some recent detective work, recently shared in a paper at the Archaeological Institute of America Annual Meeting1 in Chicago, it is now possible to present information about where they were found, as well as their modern ownership history, or provenance.

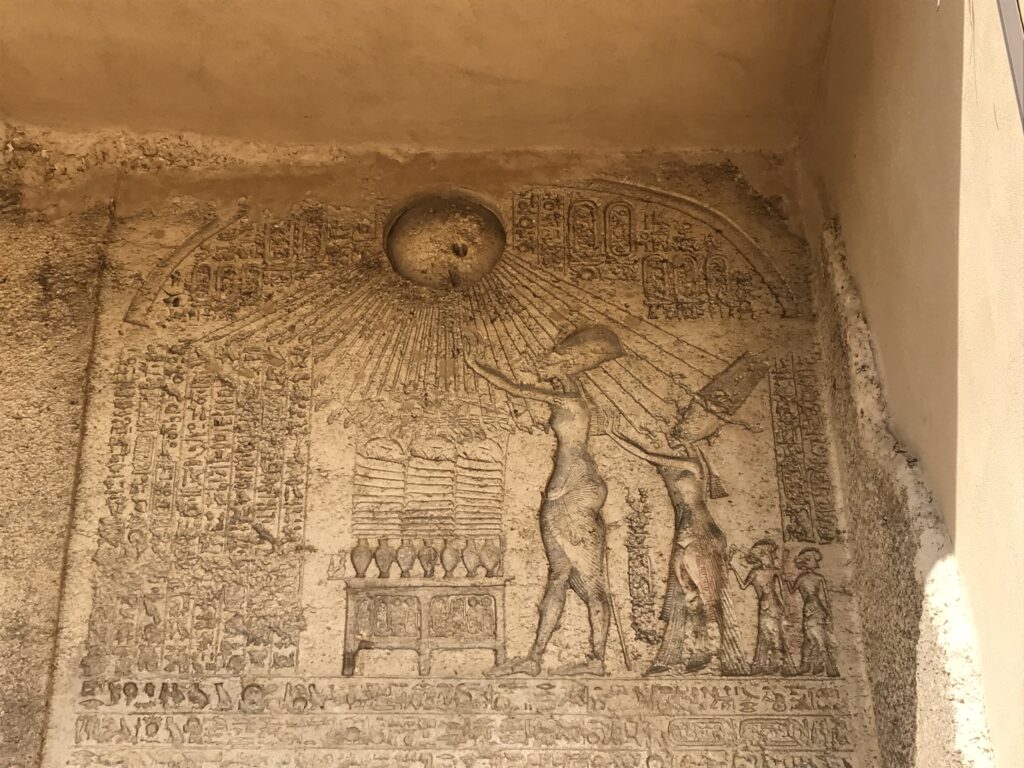

Glenn Markoe and Anne Capel researched and published the fragments in the museum’s 1996 exhibition catalog, Ars Longa, Vita Brevis: Ancient Art from the Walter I. Farmer Collection, edited by then curator, Edna C. Southard. They describe the image as a part of a common offering scene of the Amarna period in Egypt. The fragments at RCCAM show only the hips and legs of the pharaoh Akhenaten, who wears a pleated kilt and stands before floral offerings including lotus buds in a vase.

In these scenes, the deity known as the Aten was typically depicted as a solar disc with a uraeus at the edge. Rays ending in human hands extend from the symbol to touch the ruler and family members and offer them to the ankh, the symbol of life. In the RCCAM example, only the Aten’s hands are preserved, which reach down to accept the offerings.

Based on an identification of the column as “sandstone,” it was suggested by Markoe and Capel that it came from the Aten Temple at Karnak in Egypt. So the narrative was presented until last year, when preparing for an upcoming exhibition, I looked more closely at this object.

What was not mentioned in the catalog were the painted markings visible on the fragments: “22” with “333” A and B: clearly, registration numbers of some kind. I reached out to Egyptologist Emily Teeter, Associate at the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago, who suggested the fragments could come from a 1922 expedition, perhaps the Amarna expedition of the Egypt Exploration Society. She was then able to identify the object in the volume where it had been published over a century ago.2

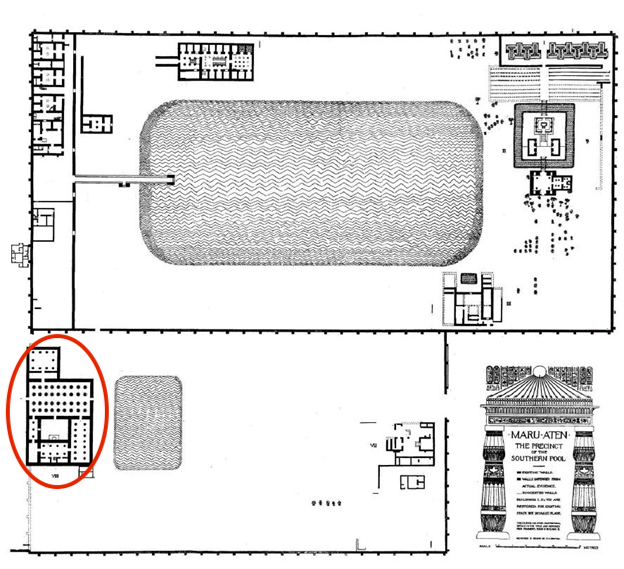

Plan of the Precinct of the Southern Pool, and the entrance hall (circled) where the column fragments were found, Peet and Woolley 1923, Pl. XXIX (Image courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society)2.

The publication indicates that the fragments were among several found in the entrance hall of the Maru-Aten, and also known as the Precinct of the Southern Pool, located around two miles south of the city of Amarna. The precinct, with its pools and gardens, was part of a cultic area in the desert apparently dedicated to female members of the royal dynasty.

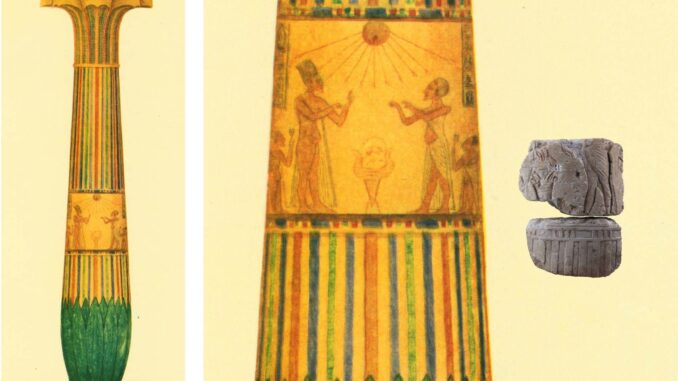

Restoration of a painted column in the Maru-Aten Entrance Hall and cropped detail with fragments alongside. Peet and Woolley 1923: Pl. XL (courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society; graphic Macey Chamberlin).

The restoration image of a typical column from the hall shows that they were once brightly colored with inlays and pigments. Next to it is shown the fragments from RCCAM.

But how did the column fragment come to Walter Farmer and then to Miami University? Stephanie Boonstra of the Egypt Exploration Society (EES) shared archival records with me identifying the Amarna fragments as coming from the official division (or “partage”) of objects from the Antiquities Service of Egypt distributed by the EES in London to subscribing institutions and museums. These fragments were from a group of artifacts from Amarna sent to the St. Louis Society of the Archaeological Institute of America in the 1920s.

What happened to the collection after it arrived in St. Louis was shared with me by Michael Fuller, secretary of the St. Louis Society. Many artifacts came to St. Louis through subscription to EES expeditions, firstly to Harageh (1914), and later Amarna (1921), and Oxyrhynchus and the Fayyum (1922). Because the Society did not have space to store the objects, they were kept at the Saint Louis Art Museum where they remained undisplayed due to their largely fragmentary and utilitarian nature.

In 1962, due to storage space challenges, the Saint Louis Art Museum and the St. Louis Society coordinated a sale of Egyptian artifacts in its sculpture gallery. The sale of archaeological objects by museums still took place at that time – a practice viewed as unethical today. The proceeds were to jointly benefit the Museum and the Society, and cover the museum’s expenses. After the sale was completed, the Museum engaged “antiques dealer” Claude Linn to purchase objects remaining after the public sale.

A sales list shared by Pat Boulware at the Saint Louis Art Museum3 suggests that an initial buyer had not been found at the 1962 sale, and that the two fragments, which were at that time were not yet mounted together, had become dissociated from each other in the listing.

While we are not sure exactly when Walter Farmer acquired the fragments, we are able to narrow down their acquisition to between 1962 and the time of its donation to Miami University in 1978. It is unclear if Walter Farmer knew they came from Amarna and were published. He had deeply personal motivations for collecting art and antiquities, and was inspired by travel, interactions with art and culture, and the people around him. This picture taken in occupied Germany shows him in 1945-6 while serving in the Monuments, Fine Arts & Archives program, also known as the “Monuments Men and Women.” He stands next to the retrieved ancient Egyptian bust of Nefertiti, viewed as an icon of Amarna Dynasty art, which after being safeguarded in Wiesbaden, went back to Berlin, where it is displayed today. Perhaps this early encounter with Amarna art was an inspiration for his later acquisition of the column fragments.

This is a cautionary tale of a private sale of an archaeological object originally intended to be kept in a public collection, and of the problem of dissociation of objects from their archival or published records. This example gives hope that such objects entering the market may resurface in the future, despite their complex modern biographies, and because of the crucial role that archives can play in their identification. Through this case study, we can see how it is possible to reconnect an object with its original findspot, historical and architectural context, association with other objects, and associated people and institutions.

Endnotes

- Green, John D.M. “Monuments Man” Walter Farmer and the formation of an Antiquities Collection at Miami University. Archaeological Institute of America Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, January 5, 2024. Session 1I: Contested Objects in Academic Collections: Legal and ethical considerations. Sponsored by Foundation for Ethical Stewardship of Cultural Heritage (FESCH).

- 113, pl. XXXII.6 in T.E. Peet & C.L. Woolley 1923, The City of Akhenaten I. London: Egypt Exploration Society.

- Archaeological Inst. of America, St. Louis Art Museum, Egyptological Material Sold at City Art Museum, Dec. 9, 1962. Former Loan Document File, E8987.1, Saint Louis Art Museum.

Jack Green, PhD, is the Jeffrey Horrell and Rodney Rose Director and Chief Curator at the Richard and Carole Cocks Art Museum, Miami University. Jack’s interests include museum and cultural heritage studies, the intersection of art and archaeology, and collections provenance research. He is a member of the American Alliance of Museums, American Society of Overseas Research, Archaeological Institute of America, and ICOM.

Support RCCAM today: to help support the activities and educational programs of Richard and Carole Cocks Art Museum, please consider becoming a member or giving a donation: givetomiamioh.org/artmuseum