Issue 3

By Zachary Logsdon Note: This op-ed is set in the late 1950s, at the time of the deployment of the first UN peacekeeping mission to the […]

Read More

By Grant Radke There can be no doubt that the United States is retreating from the world stage, and nowhere has this been more apparent […]

Read More

By Joshua Bradford A historical criticism of the United Nations is that it has been slow to respond in times of crisis. The spectre of […]

Read More

By Patrick O’Malley Since 1965, policymakers have touted international sanctions as a low-cost method to achieve international peace and security. United Nations (UN) sanctions have evolved […]

Read More

Photo: Final closing march of the literacy campaign. Dec 21, 1961. Photo by Liborio Noval By Annika Lee In 1960, Fidel Castro introduced his literacy campaign […]

Read More

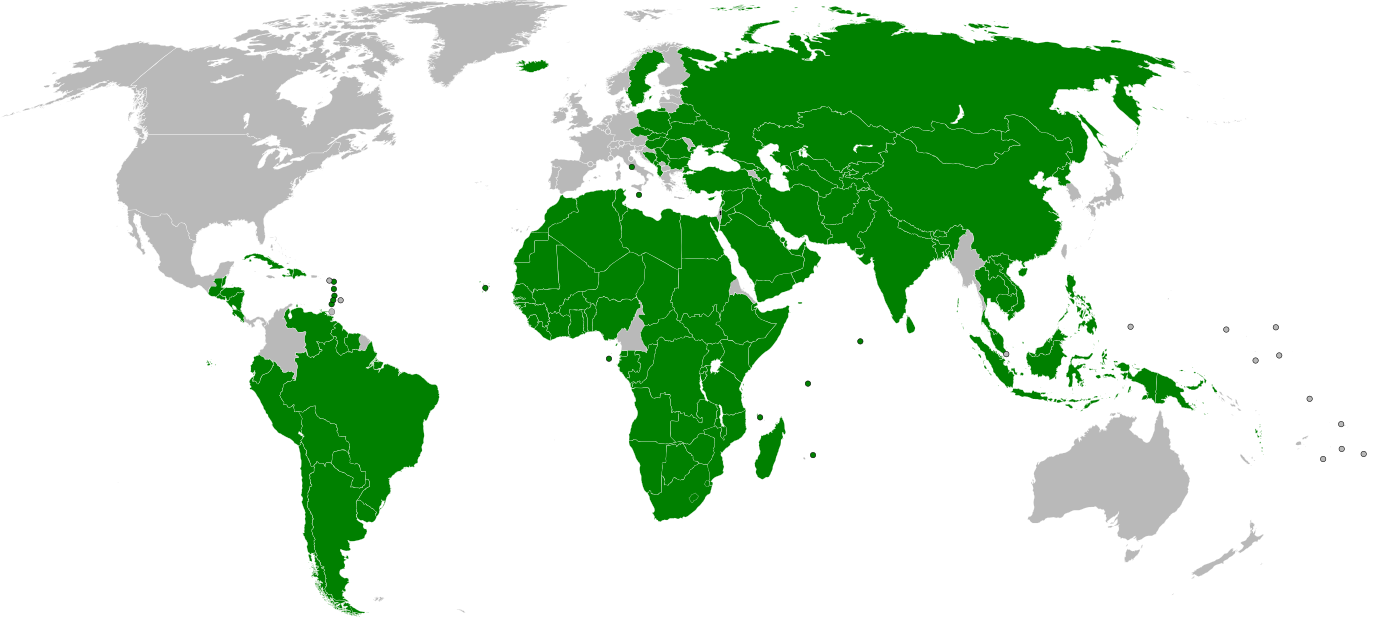

Map: Countries that have recognized the state of Palestine By Brian Carter The United Nations’ handling of the Palestine Liberation Organization throughout the 1960’s and […]

Read More

By Amanda Lawson South Korean president, Moon Jae-in and North Korean leader, Kim Jong Un met in the DMZ on April 27, 2018, each crossing […]

Read More

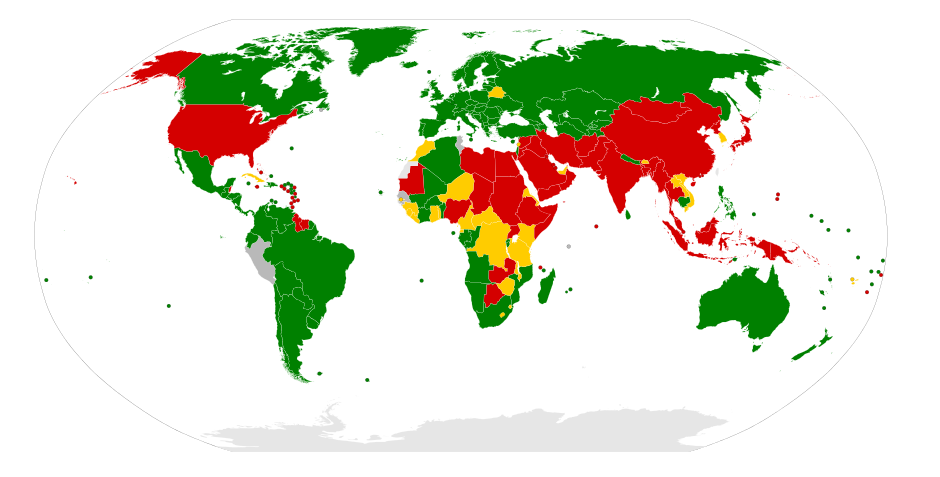

The 2008 UN Vote on the Death Penalty. Red countries voted against, green for, yellow abstained. Source: Wikimedia Commons. By Katherine Bacon In 2007 the […]

Read More

This spring, students in HST 410/510: International Organizations After World War II, researched areas of United Nations history that interested them. Along with a prospectus […]

Read More