By Art Museum Student Assistant David Shuppert

As the month of our Freedom Summer programming comes to an end, we would like to highlight and commemorate the lives lost during the fight for voters’ rights and equality.

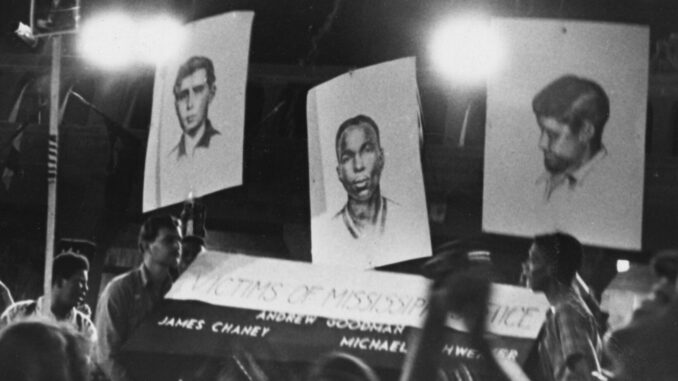

James Chaney was African American, and Andrew Goodman and Michael ‘Mickey’ Schwerner were both Jewish. Chaney started volunteering in late 1963 and joined the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in Meridian, Mississippi. Goodman’s family was devoted to social justice and progressivism, and he began attending marches at the age of 14. Schwerner became involved in civil rights work for African Americans, leading a local CORE chapter on Manhattan’s Lower East Side known as “Downtown CORE” in the early 1960s.

On June 21st, 1964, the seventh day of the Freedom Summer program, Civil Rights activists Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan in collusion with the Mississippi Neshoba County police. The disappearance of the three men resulted in a large FBI manhunt, and after 44 grueling days, the bodies of the three men were discovered in a shallow grave in Philadelphia, Mississippi, as well as their burned-down station wagon dumped in a nearby swamp (several weeks prior).

They were on their way to investigate the burning of Mt. Zion Methodist Church, which had been a site for a CORE Freedom School. When the three men failed to give their agreed check-in call from Mississippi, Freedom Summer director Robert Moses knew what had happened: they were already dead. Moses chose to share the news with the volunteers before the media could, and the air in the room became frightening. However, the silence was cut short by the hum of Freedom songs. Their courage was not snuffed out, but rather strengthened by the legacy of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner. Later, Moses repeatedly told students to consider whether they still wanted to go through with the project, but not a single volunteer of the 800 civil rights activists dropped out. Instead, they pressed forward, honoring the fallen by continuing the fight for justice. The Freedom Summer Project of 1964 went on to register more than 1,000 black voters in Mississippi and create 50 freedom schools. In 1966, the parents of Andrew Goodman—Robert and Carolyn Goodman—established The Andrew Goodman Foundation in their son’s memory, which gives young voices and votes a powerful force in today’s democracy.

In 2000, Miami University created the Freedom Summer ‘64 Memorial to honor the efforts put forth by the Freedom Summer trainers and trainees. Standing next to Kumler Chapel is the amphitheater conceived by Miami University architect Robert Keller. The memorial simultaneously operates as a learning space and a commemorative space. On each limestone seat is engraved a headline or statistic that chronologically tells the story of Freedom Summer. At the memorial’s base are three dogwood trees complimented by curling, metal branches and windchimes, installed in tribute to the three men killed in Mississippi.

In times of stress, reflecting on history and recognizing volunteers for who they truly were—ordinary individuals—can be cathartic. Like us, they were students, driven by the same passion for peace and equality. The only difference between them and us is the passage of time. By appreciating the contributions of those who came before us, we can continue to strive for positive change for our own communities.

I invite you to visit and explore Through Their Lens: Photographing Freedom Summer as it chronicles both the liberating and the haunting events that took place in 1964. Please also visit the Freedom Summer Memorial next to Kumler Chapel, which is a short 8-minute hike away from the art museum.

David Shuppert is a Senior studying Communication Design and Emerging Technology and Business Design. He works as the Art Museum Student Specialist and was the designer who created the exhibition graphics for Through Their Lens: Photographing Freedom Summer.