By Andrew Casper, Associate Professor of Art History, Miami University

I have taught at Miami University for fifteen years as a professor of Renaissance and Baroque art history. Over that span of time I have learned not to take the Miami University Art Museum for granted. Ours of course is not the only institute of higher education to have a campus museum housing art and artifacts from around the world and from many historical periods. But I am convinced that very few are as openly accessible to all members of the campus community as ours.

The Miami University Art Museum’s relationship with our major and minor in Art and Architecture History has strengthened significantly over the years. By now our partnership, both with its staff and its collection, has become a centerpiece of the undergraduate learning experience. The broad array of art and artifacts from diverse times and cultures routinely augments classroom instruction with authentic hands-on and object-based learning opportunities for students in most of our courses.

However, despite the pedagogical prominence of the Art Museum for our students, few know how the collection shapes their professors’ own scholarly work outside of the classroom. Indeed, students often are unaware that we do have professional lives beyond our teaching. It is important to broadcast the ways our museum bridges what is too often seen as a gap that separates our duties as teachers in the classroom from our responsibilities as active scholars in our fields.

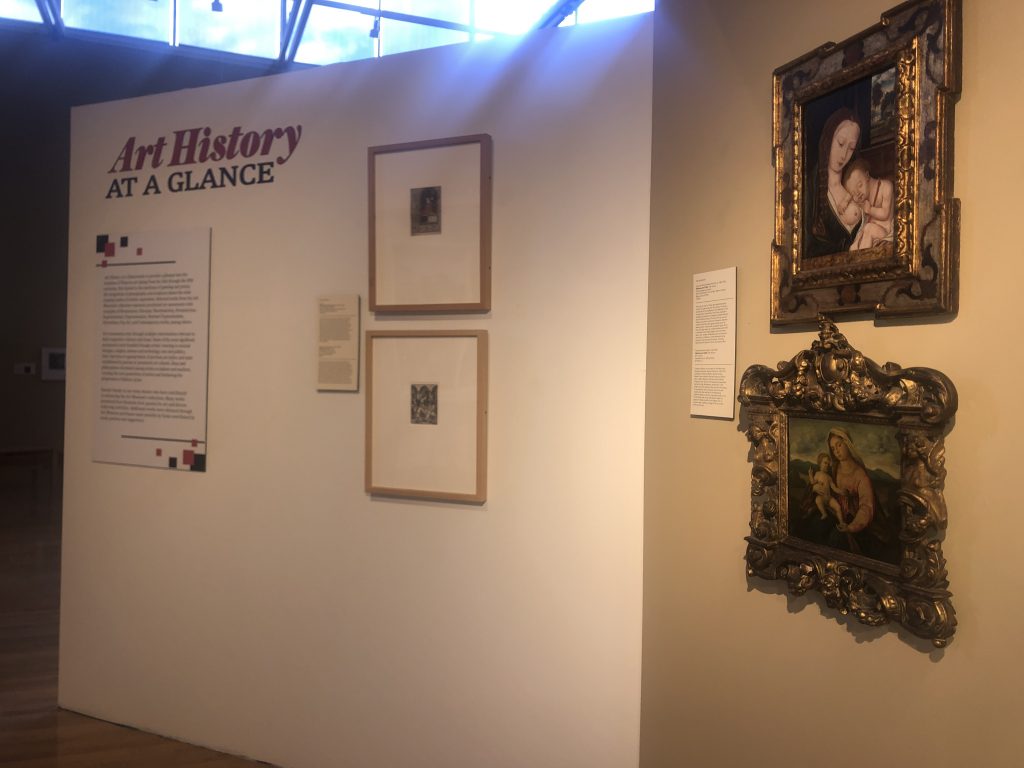

When I first came to Miami University to interview for my current position I was taken to the art museum’s storage room, filled with images and objects hanging on racks and stuffed in drawers. It was then where I first saw Francesco Bissolo’s Madonna and Child (early 1500s)–at the time hidden from view, but now a perennial feature of the Art History at a Glance permanent exhibition at the museum. In no way is this painting on the same caliber as those that form the traditional Renaissance art history canon. But this is precisely why it’s such an important and ultimately illuminating work. It is far more representative of the kinds of images for private devotional purposes that were commonly found in domestic settings of Renaissance Italy. While paintings by Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo da Vinci are justifiably famous and significant to the history of art, they are outliers–wholly unconventional in their fame and recognition as masterpieces even in their own day. By contrast, Francesco Bissolo’s modest Madonna, the likes of which one does not often see in the world’s most famous art museums, has helped shape my own perception of the more common and typical roles played by images in society at that time and place.

In 2009, just two years after being hired as a professor of art history, I presented a lecture at MUAM centered around this painting titled “Miami’s Madonnas and the Renaissance of the Icon.” That lecture became instrumental in the development of one theme that runs through my first book Art and the Religious Image In El Greco’s Italy (Penn State University Press, 2014). While this book does not address Bissolo’s painting specifically, the themes that coalesced around it as I explored its form, function, and context helped me better understand how the early paintings of El Greco made in Venice and Rome would have functioned in ways that encompass the legacy of medieval devotional icons–a continuity that has not been sufficiently recognized by scholars of Renaissance art history. Consequently, my book on El Greco, spurred in part by my reflections afforded by the Bissolo Madonna and Child here at Miami University, has made significant innovative contributions to the prevailing scholarship in my field.

My research activities have continued to pursue the broad question of the religious icon in Renaissance and Baroque Italy. And I am not the only one. On April 26th I am delighted to join my friend and colleague Professor Wietse de Boer from Miami’s Department of History in a panel discussion entitled Art, Religion, and the End of the Renaissance. Since we are both currently teaching classes on the theme of the Italian Renaissance (ART 315: High Renaissance and Mannerism and HST 315: The Renaissance), this event aims to draw the Museum’s collection into mutual dialogue with the research activities that we pursue outside the classroom and the courses that we teach. Though we are scholars in different disciplines, we each study the role of Christian images in the early-modern period in Italy. We both have recently published books that make important contributions to the existing scholarship in this fertile and important period in the history of art. Wietse de Boer’s Art in Dispute: Catholic Debates at the Time of Trent (Brill, 2021) examines the theological debates surrounding the validity of religious imagery during a time of great consternation within the Christian church–controversies that ultimately led, in the sixteenth century, to the Reformation and the split of the Protestants from the Catholics. In this important contribution to the existing scholarship on Counter-Reformation image debates, Prof. De Boer analyzes a selection of previously under-examined texts from the years preceding the Catholic Church’s official statement reaffirming the validity of sacred images from the Council of Trent (1563). My own book An Artful Relic: The Shroud of Turin in Baroque Italy (Penn State University Press, 2021) examines in detail the history and reception of a particular object that found itself deeply intertwined with those same debates described in Prof. De Boer’s book. This the Shroud of Turin, the supposed burial cloth of Jesus that contains (for believers) a miraculous imprint of Jesus Christ’s dead body replete with stains of blood. From the late 1500s through 1600s this Shroud was regarded as the preeminent religious image–one sanctioned by God, and even credited to creation through miraculous means as a divine painting.

As scholars of the same period, even if from distinct academic disciplines, we have both benefit from the close proximity to images in the collections of the Miami University Art Museum that originated in the periods of these conflicts and which therefore provide clear and concrete insights into this complex period in the history of Christian imagery. Join us on April 26th and see how!

Author Talk on April 26, 3:30-5 PM, in person at Miami University Art Museum (Event Link)

Art, Religion, and the End of the Renaissance

Professors Andrew Casper (Art and Architecture History) and Wietse de Boer (History) have recently published books that offer significant new insights into the contentious issues surrounding the impact of the Reformation crisis and Catholic reform on the visual arts in Italy and other parts of the Catholic world in the second half of the 1500s. Following brief introductions by Professors Casper and De Boer, student panelists will moderate a conversation with them and the audience on the theme of the event. This discussion, in conjunction with courses that both will be teaching in the spring semester, will provide a forum in which they can share the major themes and topics from their books, as well as provide context for this important period in the history of art, culture, and religion. This event will feature works of art from the Miami University Art Museum to share the latest insights into the role of visual images for devotion, the theological debates about the validity of images, controversies that arose in response to the Protestant Reformation, and other themes.

Image: Santi di Tito, Vision of St. Thomas Aquinas (1593)

Andrew Casper is Associate Professor of Art History at Miami University and teaches courses in Renaissance and Baroque art history (1300-1700) and is the program coordinator for the major and minor in Art and Architecture History. He earned his BA from the University of Michigan and M.A. and Ph.D from the University of Pennsylvania. Since coming to Miami University he has published widely in his area of research, which focuses on religious imagery in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries in Italy.

On twitter: @AndrewRCasper1